PROJECT 1: Body of Work

I will share a final body of work, with a written plan that articulates a draft selection for assessment of what ideas I am communicating, identifying gaps, looking at areas that need refining, and trying to resolve these. I think of this part as drawing the threads of my exploration together and showing resolved work.

My motivation since the previous assignment and tutorial was inspired by: “….try to work beyond what seems possible and continue to take risks. Avoid settling into known methods and practices; you should still be able to step out of your comfort zone and be surprised by the work.‘ (from the study material)

Work that ‘speaks‘ to each other, links and connect

- Smaller-made nests: I can combine them as groups or place them with drawings shared in the first three images.

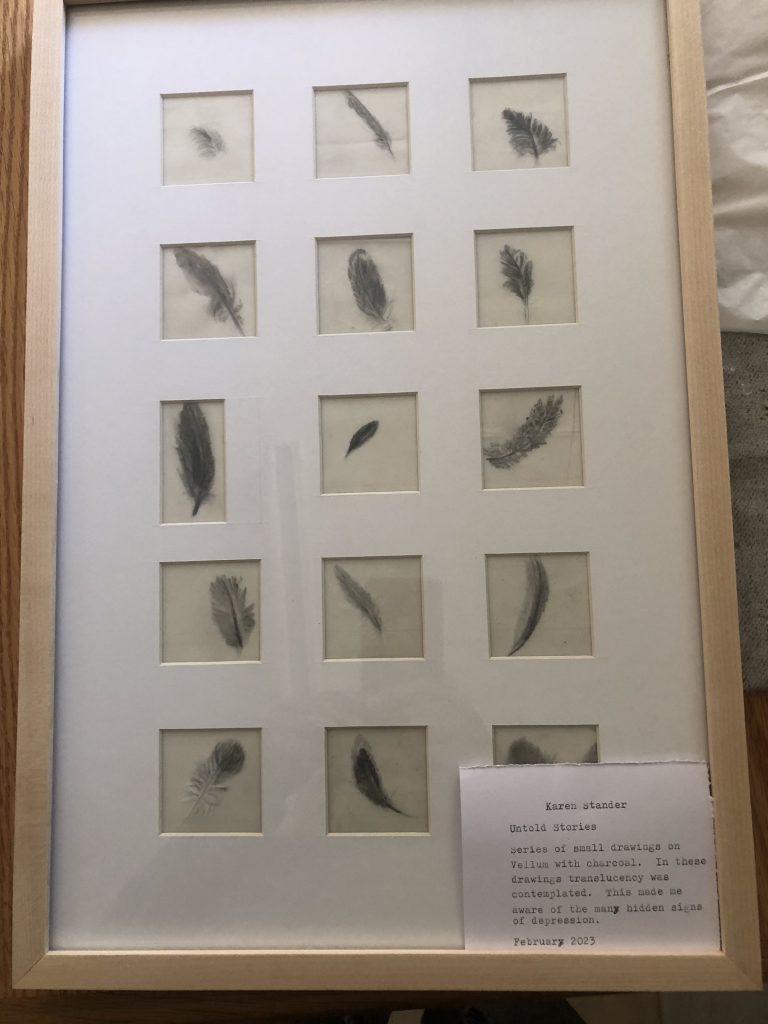

- Nests and feather drawings

- Nests hanging outside in nature as installation work.

- Upscaled nest drawing on paper and canvas.

I feel it necessary to state that most of my making was an exploration of materials and trying to act with the materials I used. It became more of an enquiry into the process of making and how forms and textures could be applied or achieved. It made me ask questions about objects versus material, substance and matter and how these materials could tell stories about their histories. By looking specifically at the sociable weaver birds of Southern Africa, I learned to appreciate their unique way of making and living as a species. I feel I learned from the birds themselves to create but also to tell their stories.

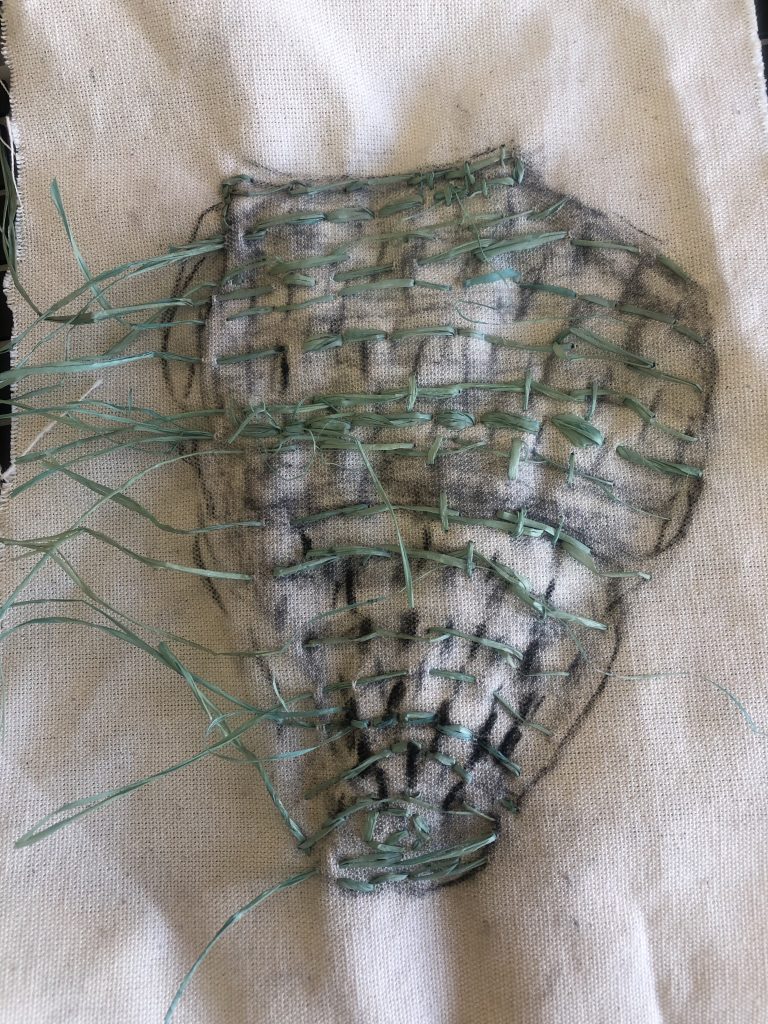

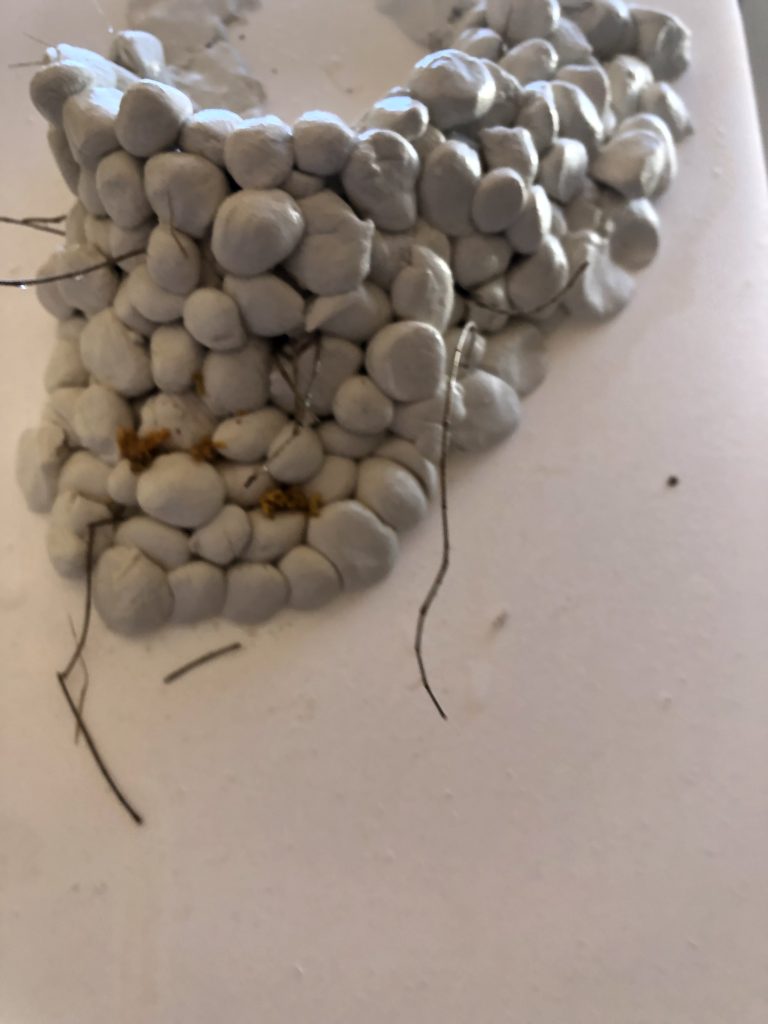

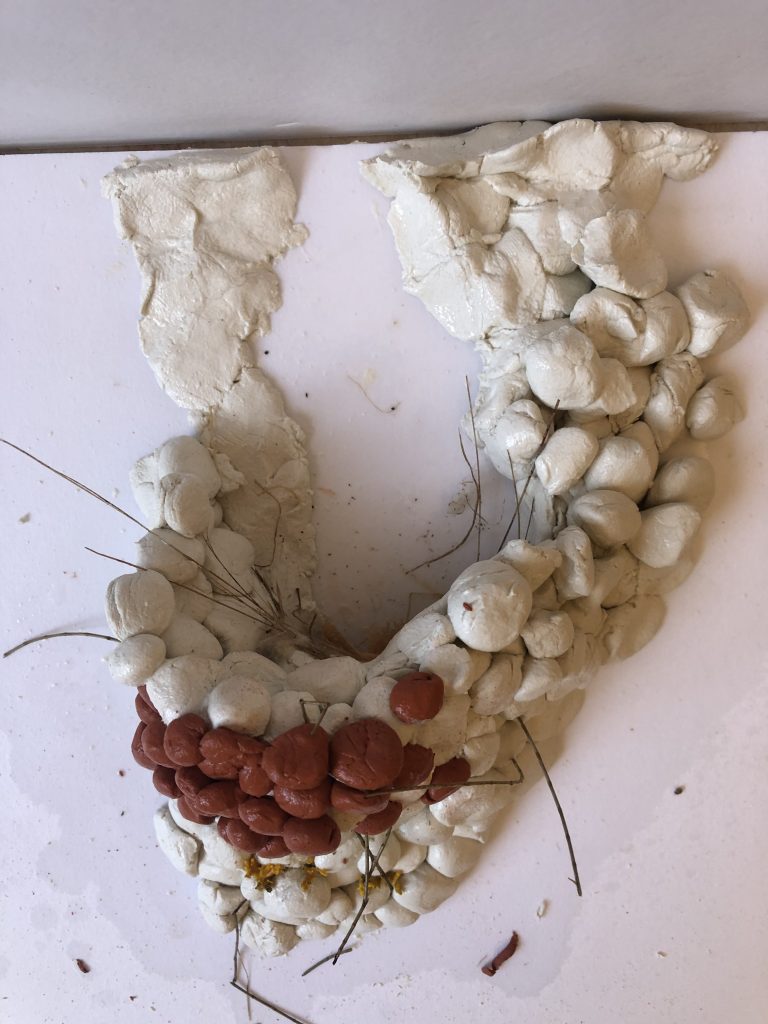

Making nests with a weaving process is a form of moulding – I would like to say they are sculptures. My making became about tactility – touching, looking at what I am trying to make, and learning from the materials. Nests that birds make do not only consist of grass or plant fibres; horse hair, human hair, feathers, plastic, wool, moss, and twine are some of the materials found in these nests. It allowed me to explore other materials and found objects.

Nests are sculptural forms and can become installations

Considering the form of the sociable weaver’s nests as sculptures. Fig. 15 and Fig. 16 made with raffia, and Fig. 17 is made with paper.

Work that communicates my ideas effectively

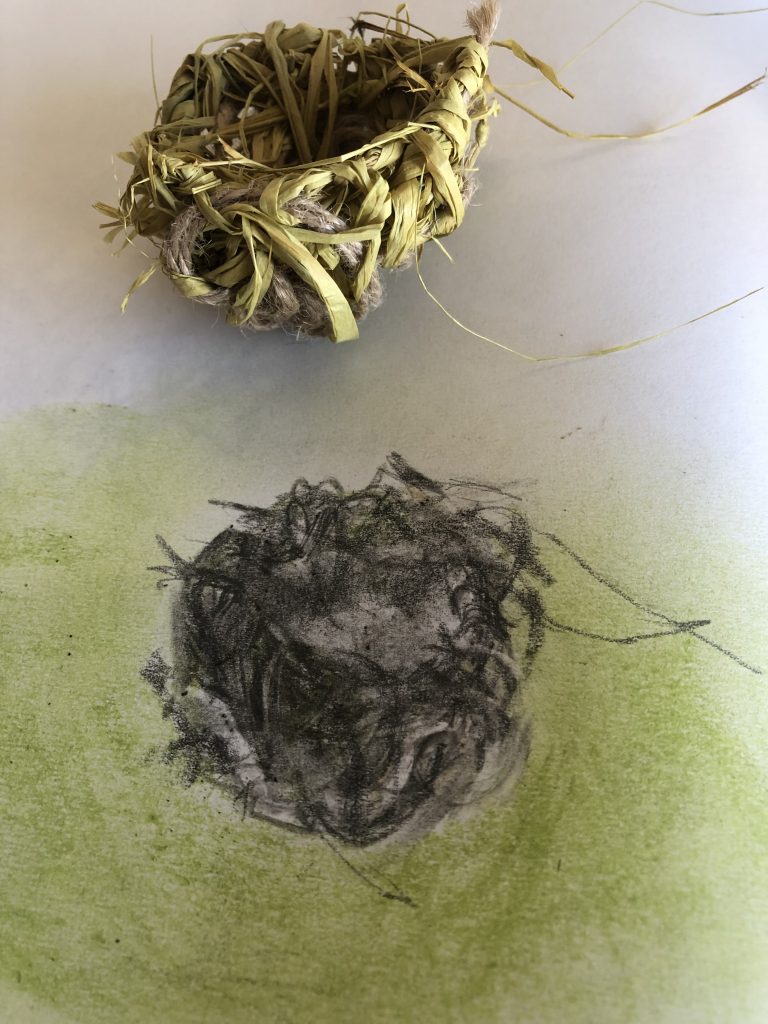

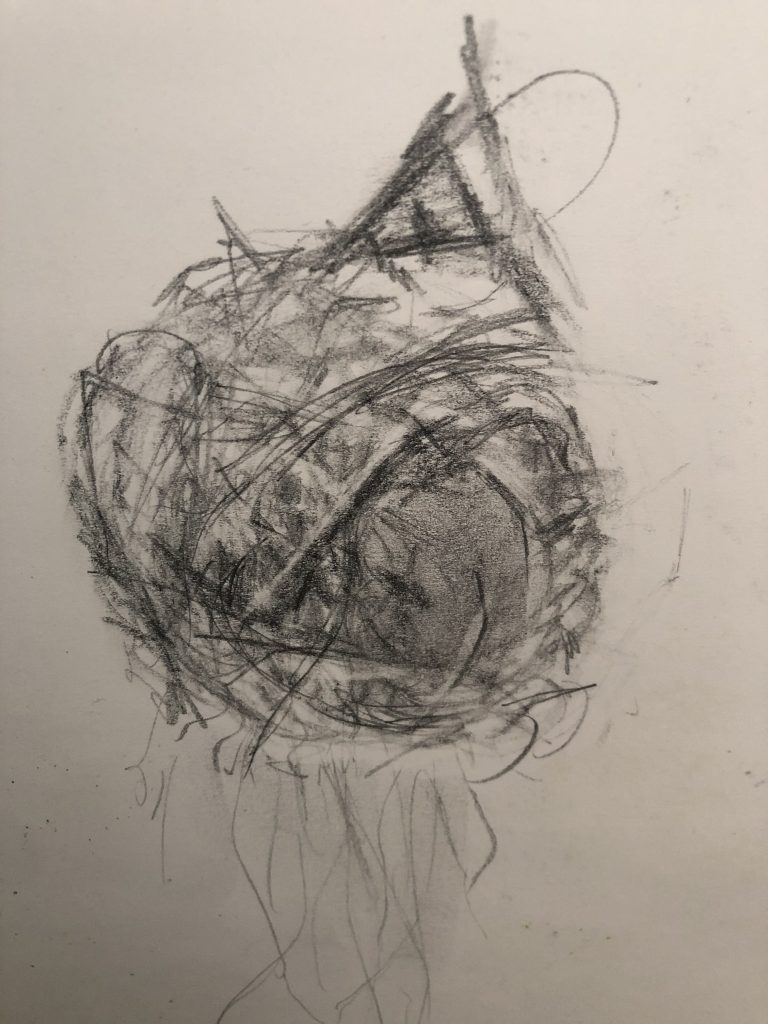

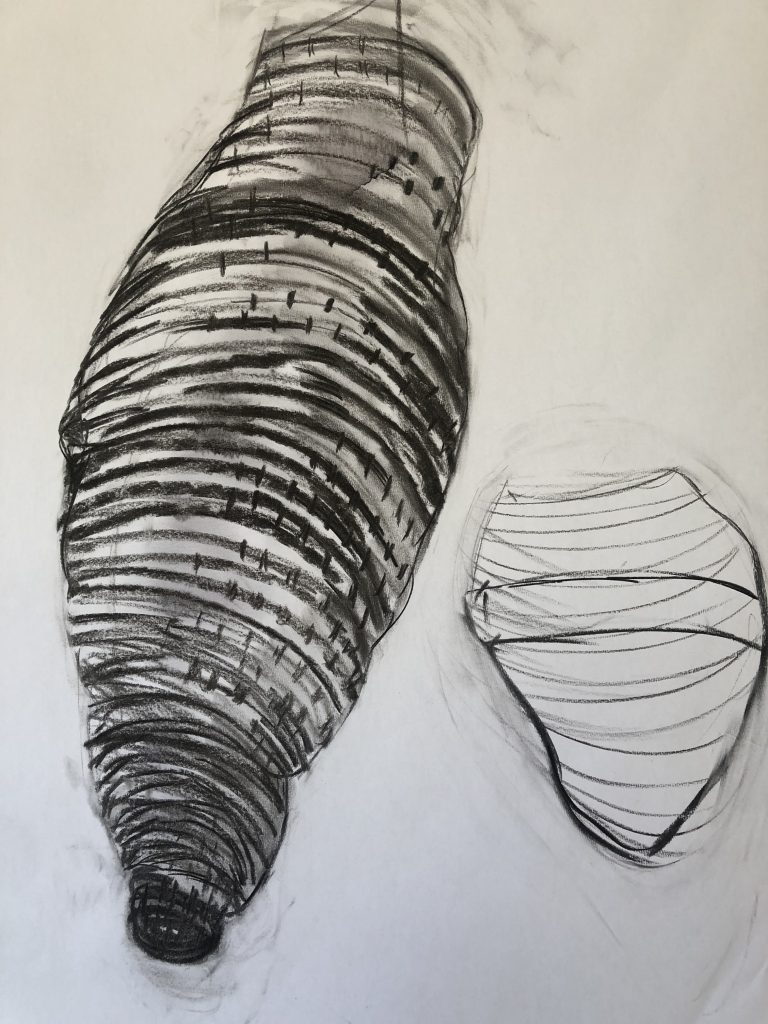

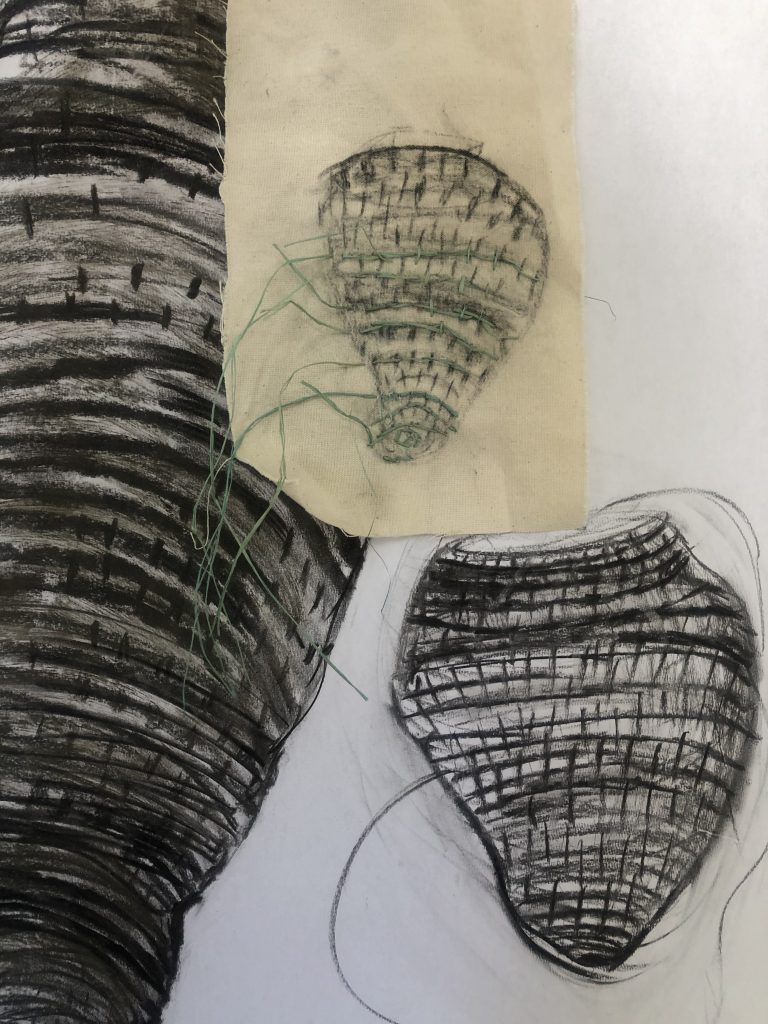

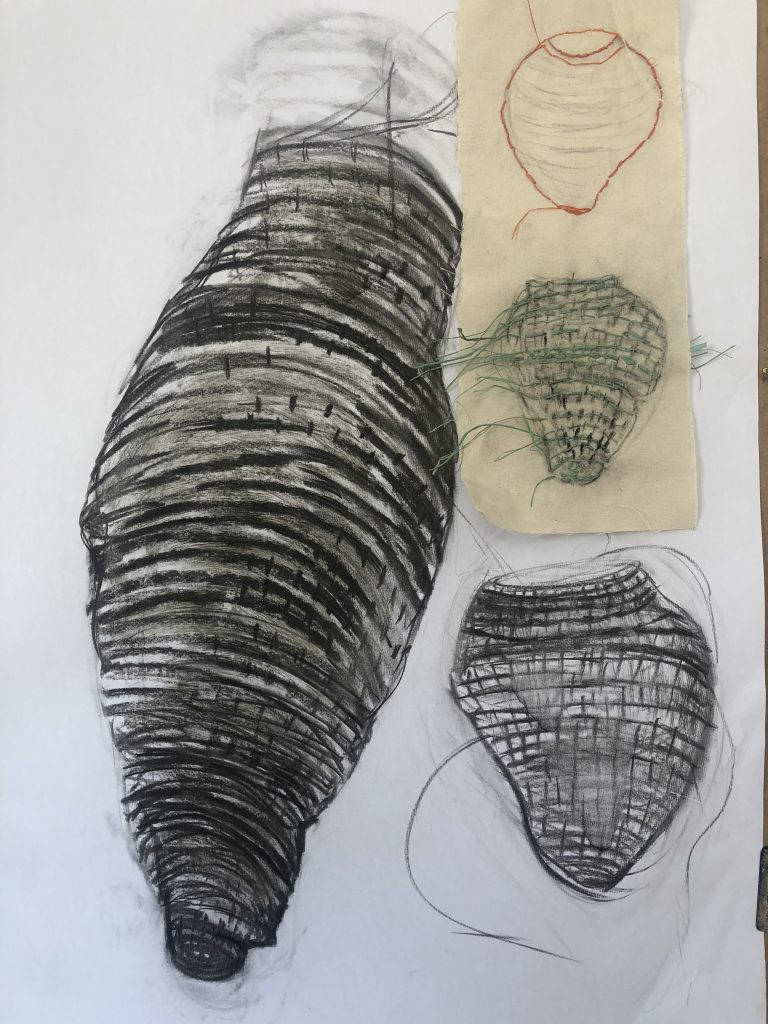

The nest drawings that became bigger communicate a feeling of exploring the non-human and finding links with care—drawings with charcoal showing textural qualities and contrast between light and dark tones, which can become ethereal for viewers.

Work continued to develop as I contemplated lines, shape and texture with weaving and drawing.

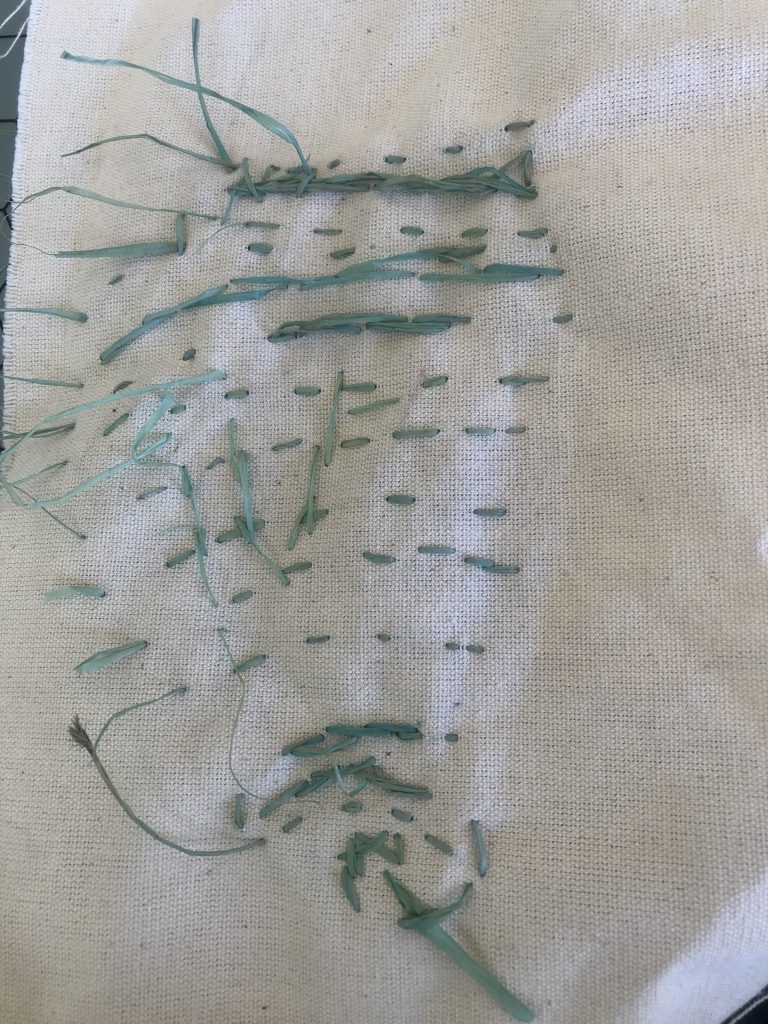

I explored more basket-weaving techniques and made drawings of my work.

I am not sure where this exploration is taking me. I see possibilities that remind me of my reading of Haraway and Le Guin and how I could challenge the narratives of safety and our connection with nature as a place to contemplate our vulnerabilities.

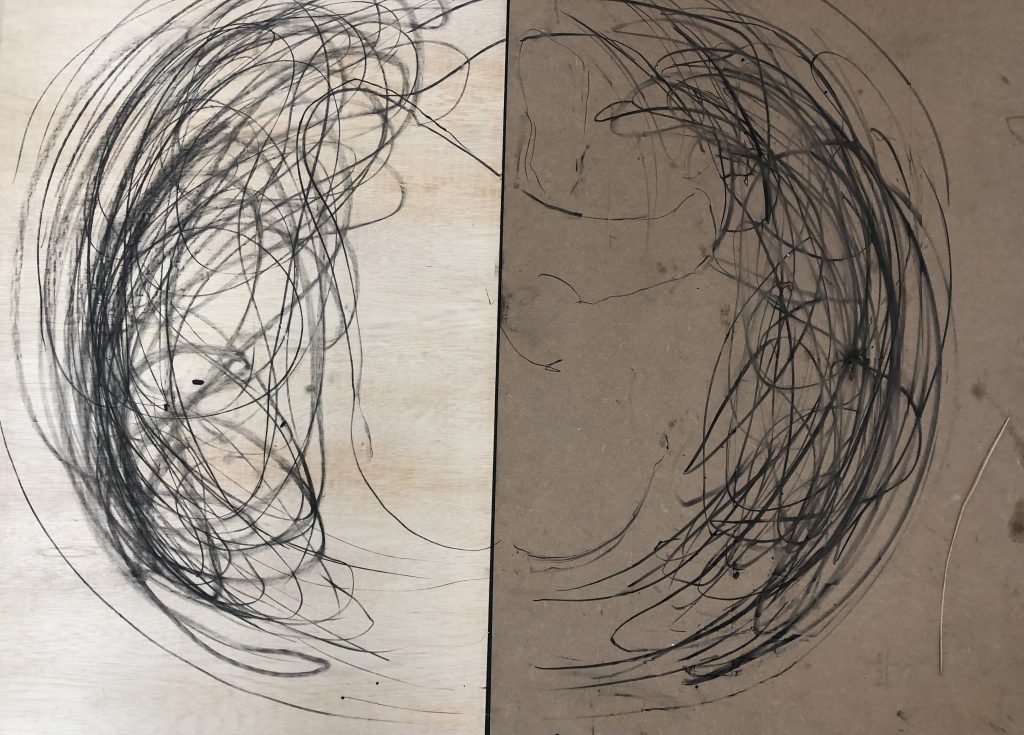

I explored drawing with my body and thinking of a nest as an oval or round form whilst seated in the drawing area and drawing with both hands. The image below was taken after 4 min of drawing.

When I started to weave nests, I looked at techniques basket makers would use. I would weave found vines together with raffia material. Earlier in the course, I bought a book by Ruth Woods, Finding Form with Fibre, and her work highlights techniques of sculptural basketry. Traditionally, handwoven baskets served practical purposes such as storage, transportation, and containers for food. The need for practicality and functionality primarily drove the craftsmanship. This traditional way of basket weaving often involves using locally sourced and sustainable materials, such as plant fibres. The craft is inherently tied to environmental considerations, utilizing natural resources to align with ecological principles.

Weaving holds a fundamental and ancient role in human society. In my own country, there is a deep cultural, symbolic, and mythological significance, and it is not just a practical skill. I thought it had been woven into the fabric of human existence: I like seeing it as part of a cohesive cultural structure, and I recently started researching the work of artists who focus on these ideas in their making. I want to develop this in the next part of my studies. Weaving can serve as a metaphor for the interconnectedness of life. Interlacing individual threads to create a cohesive fabric mirrors the interdependence of individuals within a community or the overall tapestry of existence. On a personal level, I find this way of being mindful, quiet, and meditative – a space to think and be open to new ideas of making.

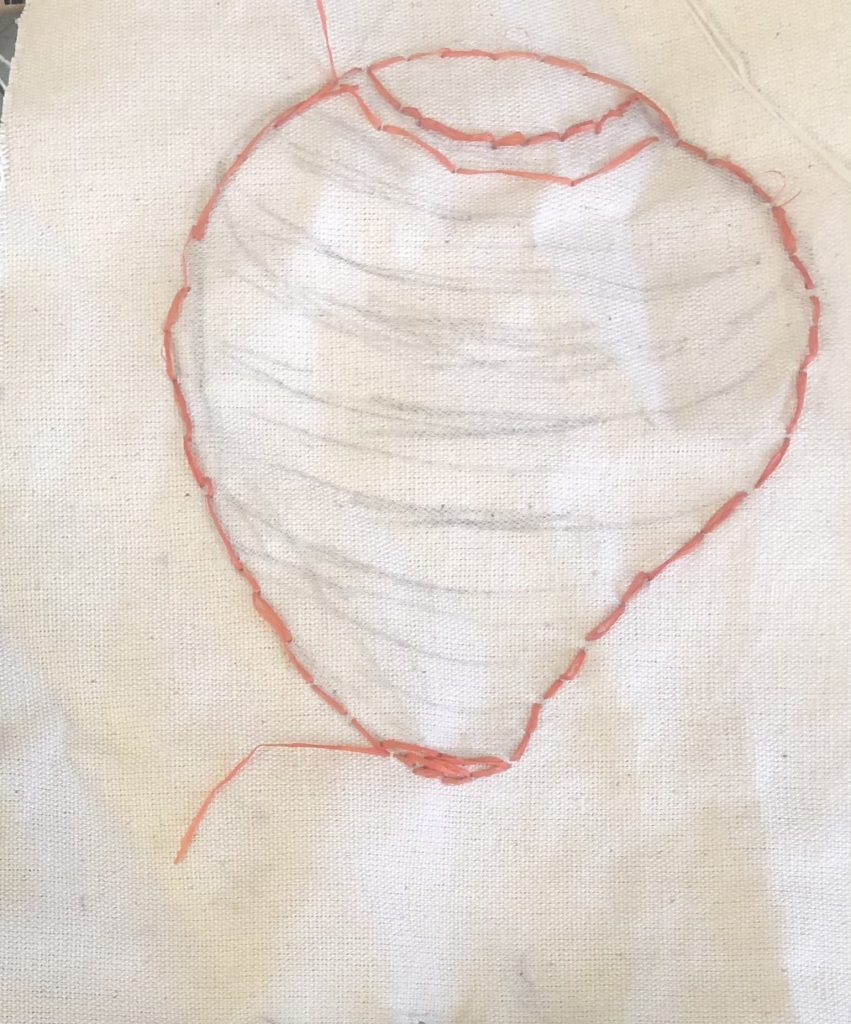

I also considered lines made with needle and raffia thread onto a drawing on canvas and looked at the work as a collage. The making was intuitive as I progressed and made another with orange lines.

A collage

I made a second container, which is still a work in progress (46cm tall), aiming to make it taller.

Mostly, the work with mushrooms did not work out as I was not successful at cultivating it. I tried working with coloured twine; and experimenting with new materials, and it seems I cannot manipulate the form quickly. I want to bring colour into my work and explore the textures and forms I could create from the different twines.

Works that are less able to communicate my ideas

Gaps identified and areas that need refining

In contemporary art, woven objects depart from functionality, focusing on the conceptual and aesthetic aspects rather than practical purposes. I explore more by experimenting with form, scale, and materials, pushing the boundaries of what is traditionally considered a basket. The emphasis can shift from strictly adhering to traditional patterns to creating unique, personal statements that reflect my vision and voice. I can develop my making by engaging in cross-disciplinary collaborations and integrating ideas around basket weaving with other art forms such as sculpture, painting, or performance. This interdisciplinary approach should expand the possibilities of what basketry can achieve.

In my research, I came upon the following work, which confirms my idea that sculpture and painting can be integrated into this making. This work, a brown reed and paper basket, was made by Mary Merkel Hess (1989). The dimensions are 55.9 x 30.5 x 30.5 cm.

Weaving forms made by hand with plant fibres navigate a dynamic space between traditional craft and contemporary art. While it retains its roots in cultural heritage and craftsmanship, it also undergoes transformation and reinterpretation in the hands of contemporary artists, pushing the boundaries of sculpture and artistic expression. This dual perspective highlights the rich versatility of basket weaving as both a craft deeply embedded in tradition and a form of contemporary artistic exploration.

List of illustrations

Bibliography

Lange-Berndt, Petra. (2015) How to be complicit with Materials Materiality, Documents of Contemporary Art Whitechapel MIT Press Page 12 – 23

Woods, Ruth. (2022). Finding form with Fibre. Published by Ruth Woods, Healesville, Victoria 3777 Australia.