PROJECT 1a : Art as Life and The Everyday

Considering the every day in my work

My studio days are driven mainly by the projects I am working on for Research and Advanced practice. I try to work with daily drawings regularly, keep them in sketchbooks and share them on social media. I recently read two articles which helped me focus on my process of making and the learning and thinking that takes place in this space, which is about embodied knowledge and haptic experience.

I have created different sites for my work and call them ‘para’-sites after N Mayers in the chapter on Para-site as Research. (. ) where a para-site is described as an exercise that “lies within and in relation to the production of (primarily) dissertation research projects by graduate students”.

“This space is analogous to the classic “native point of view” but without a compass in traditional ethnographic practices to do this kind of research that requires collaborative conceptual work. This work needs a context, a space, a set of expectations and norms better than the opportunis- tic conversations that occur in just “hanging out.” The para-site experiment is intended to be a surrogate for these needs of contemporary research that are certainly anticipated in practice but are still without norms and forms of method. It encourages addressing issues of design before a concept of design has reinvented the expectations of pedagogy in anthropological training. Undoubtedly, the para-site will take different shapes and partici- pations between the field and the conference room in other dissertation projects. But in all cases it is a response to the imperative to materialize collaborative forms in contemporary ethnographic research.”

John Dunnigan -Thingking, 2013 (pdf)

Dunnigan focuses on what happens between making and thinking and suggests that artists and designers are “form givers who bring ideas into the material world”. He describes how, in the studio, thinking about things is part of making and thinking around and through things. He then suggests this as thingking. To him, thingking expresses a symbiotic relationship – meaning that this happens between making and thinking in art and design and between object and idea. (I like that this takes me to connectivity…) What caught my attention is how this process connects critical making and critical thinking by showing how the process relies on embodied knowledge, practice, and research. He suggests this process integrates multiple ways of knowing and promotes holistic reflection and learning. This idea also involves sharing work: “We brought forth a thing and it shaped us as we shaped it. Thingking.”

Sharing my body of work

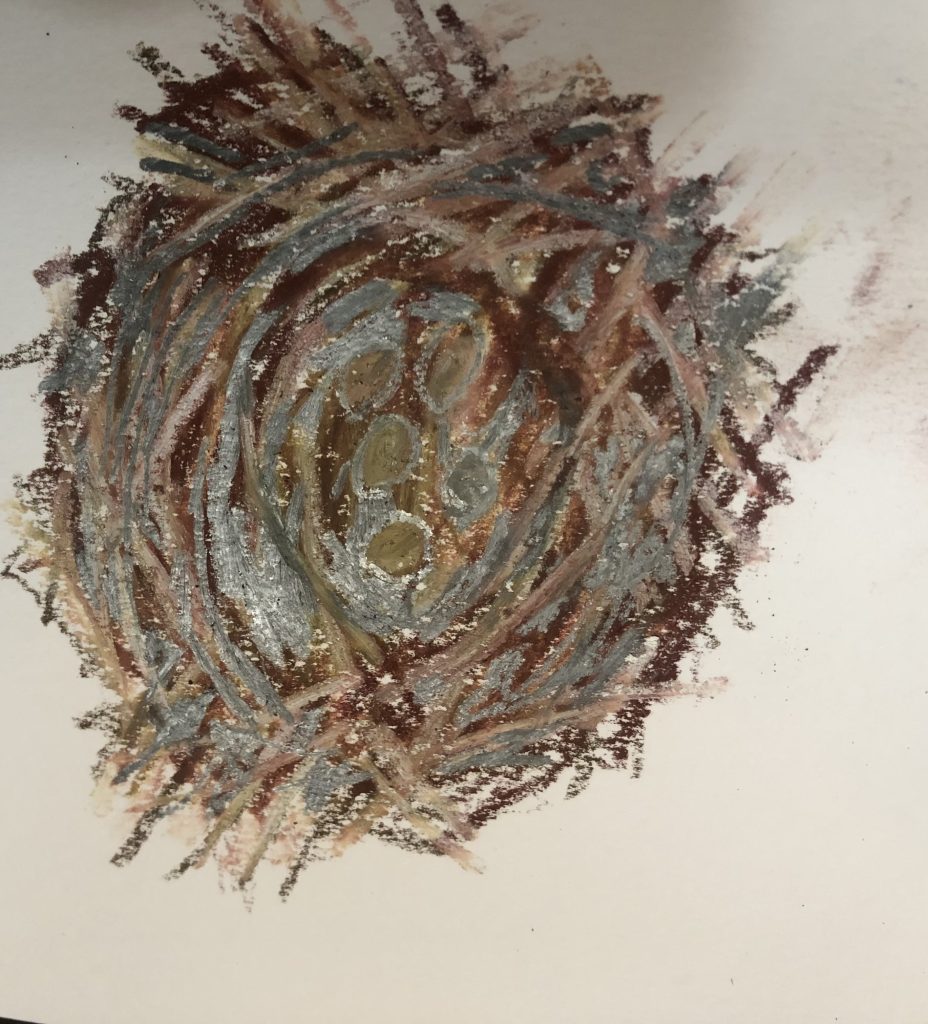

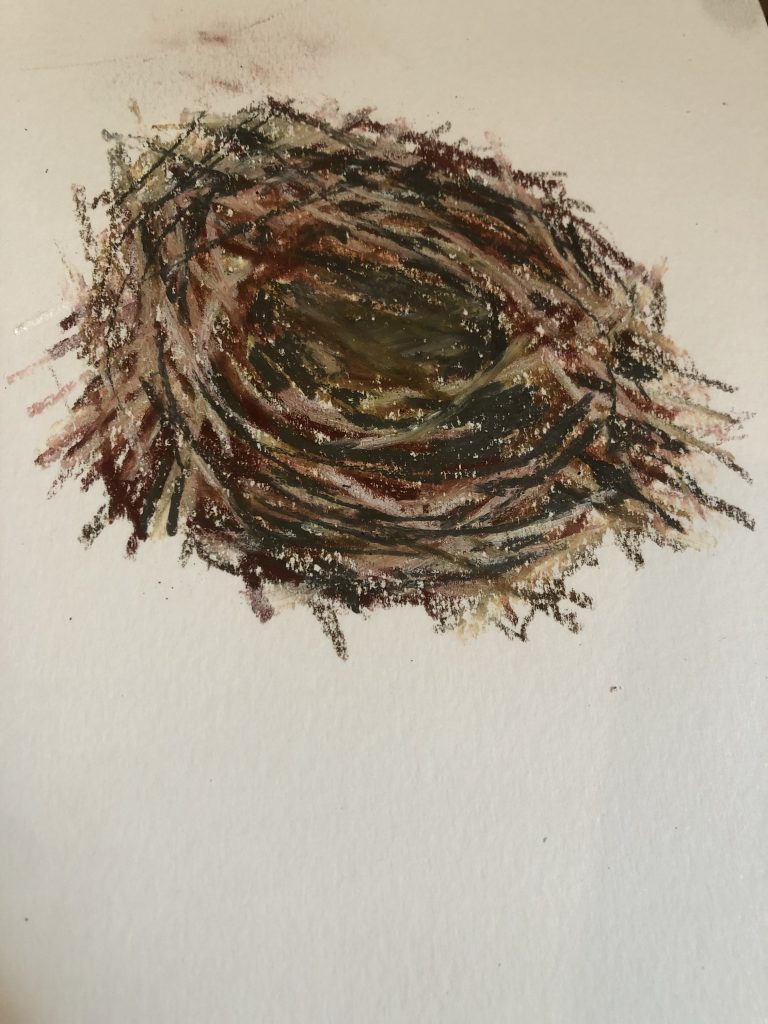

In terms of my making: nests and birds. I am considering my animalness and vulnerabilities. Conversely, it makes me think about human arrogance and how we cross into this liminal space. It is in the making experience where the thinking happens and hopefully develops as further work and insight. When I weave a nest, I often manipulate my materials by attempting to keep the shape – it makes me think of control and how, as humans, we operate within nature using these mechanisms. In my drawing I can explore the form and enjoy the craftship of the non-human in this object. I am also reminded of the different meanings a nest can have. An artist whose work I have been researching, Bartuscova considered her work around a nest, as a home, but also as a space that support creative and spiritual development, when she created Untitled, 1985. (see below) This work was made with plaster, string and hessian.

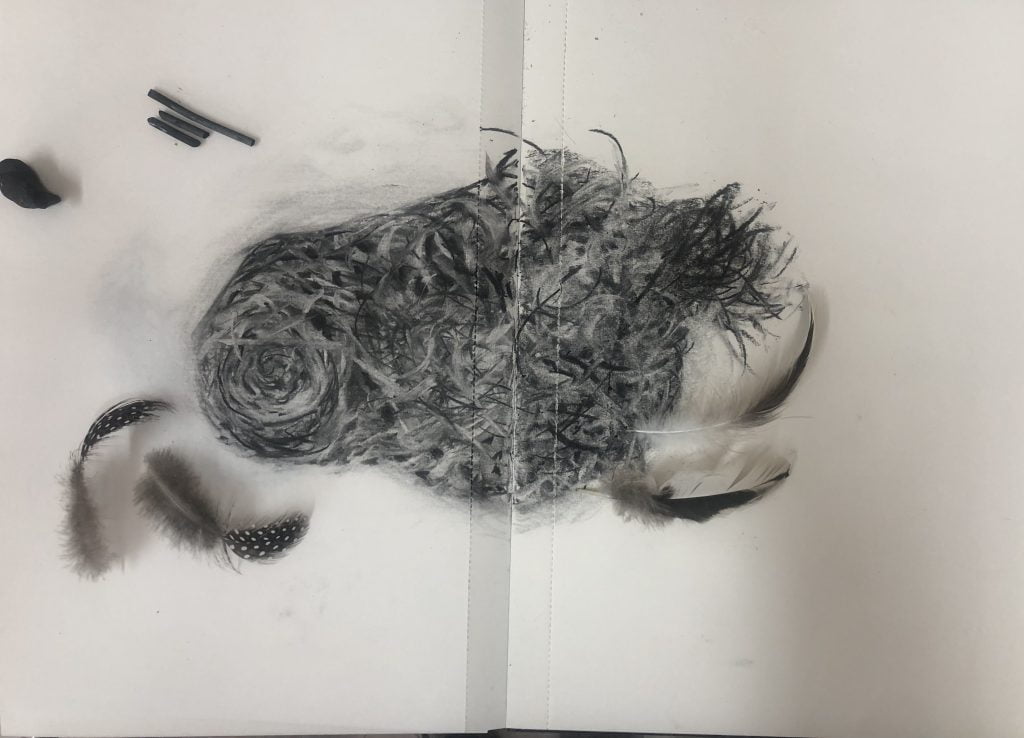

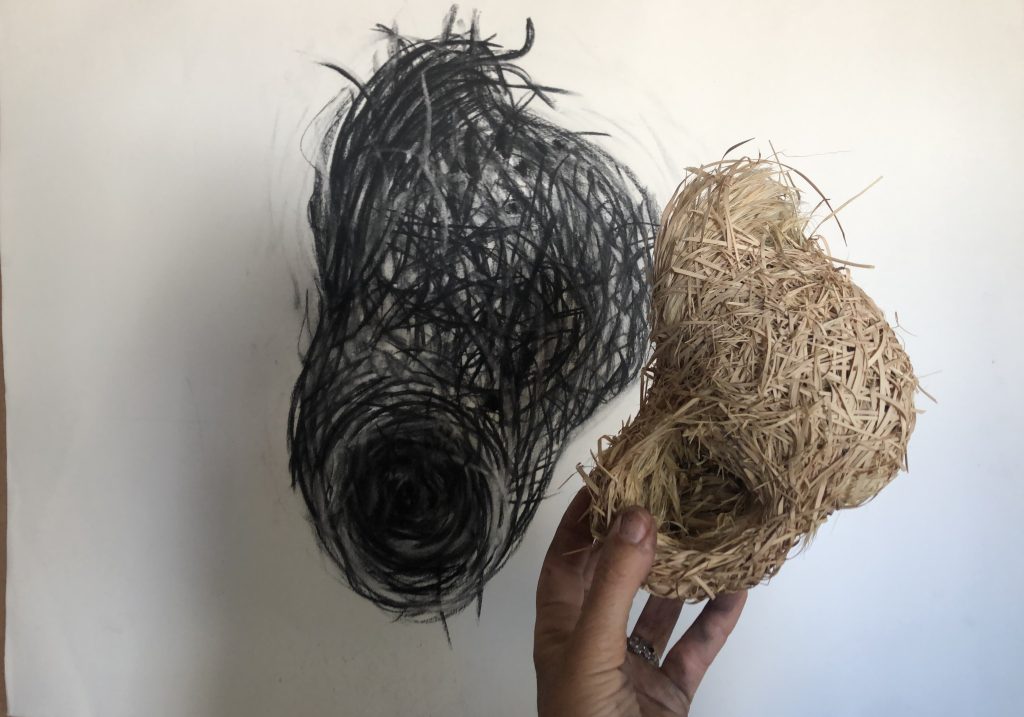

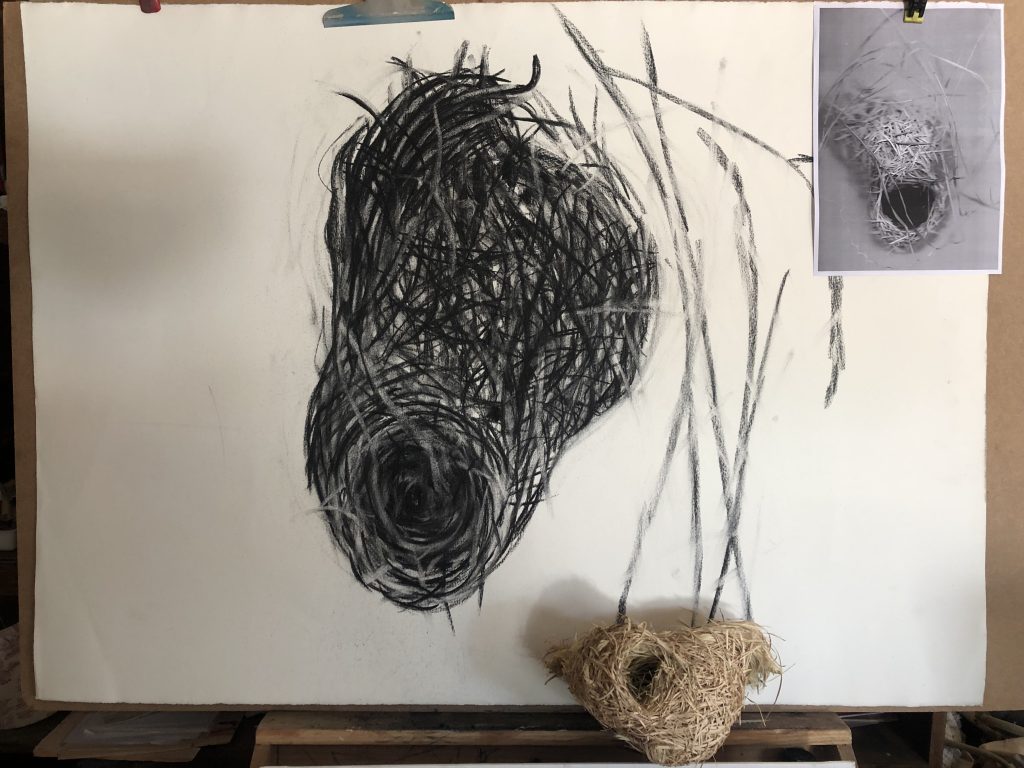

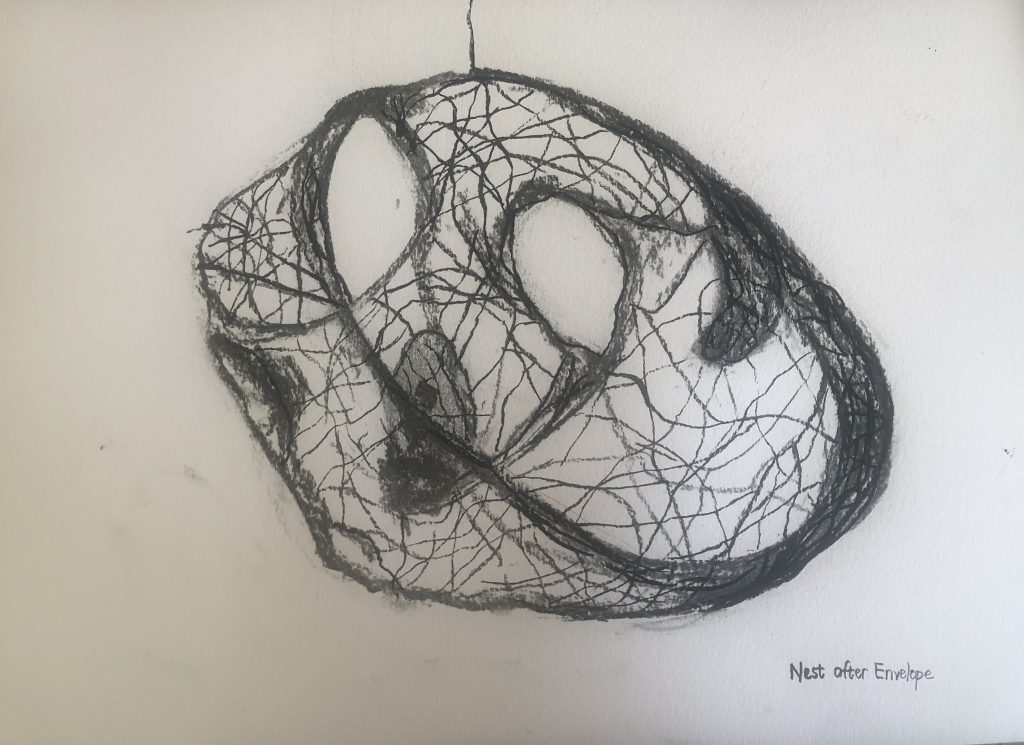

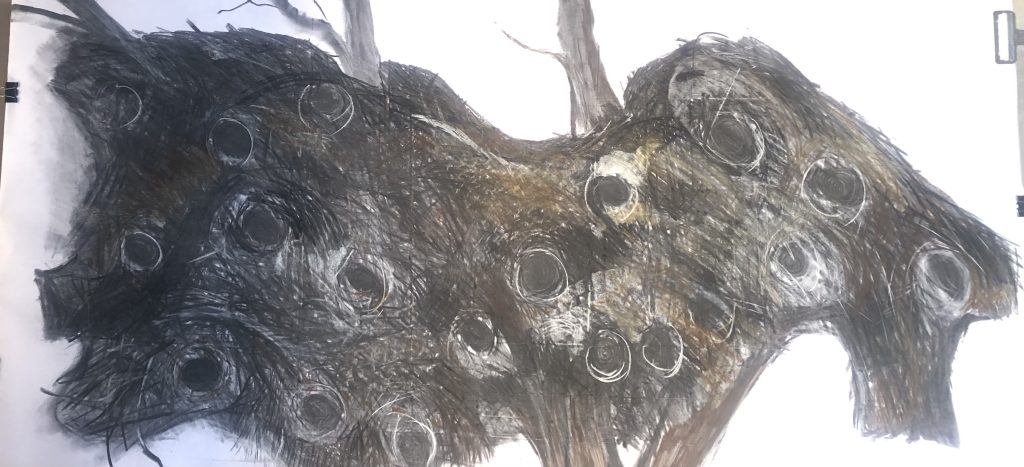

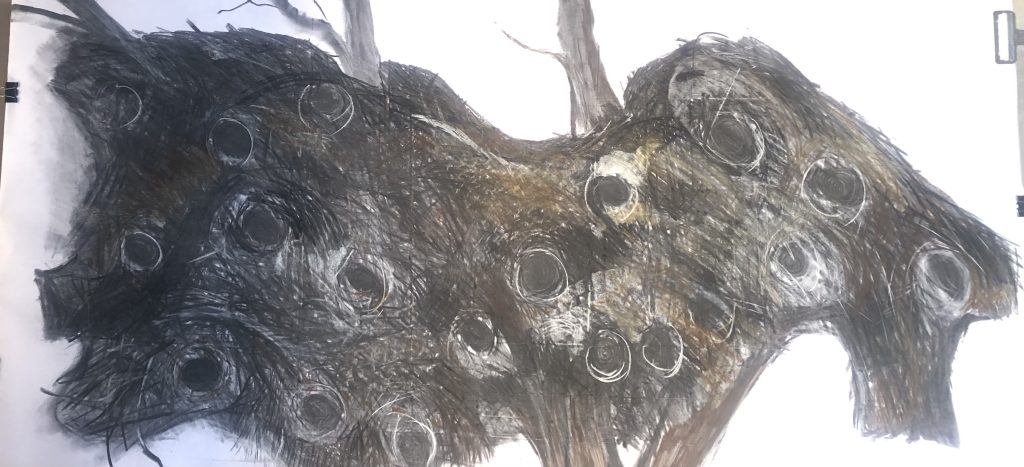

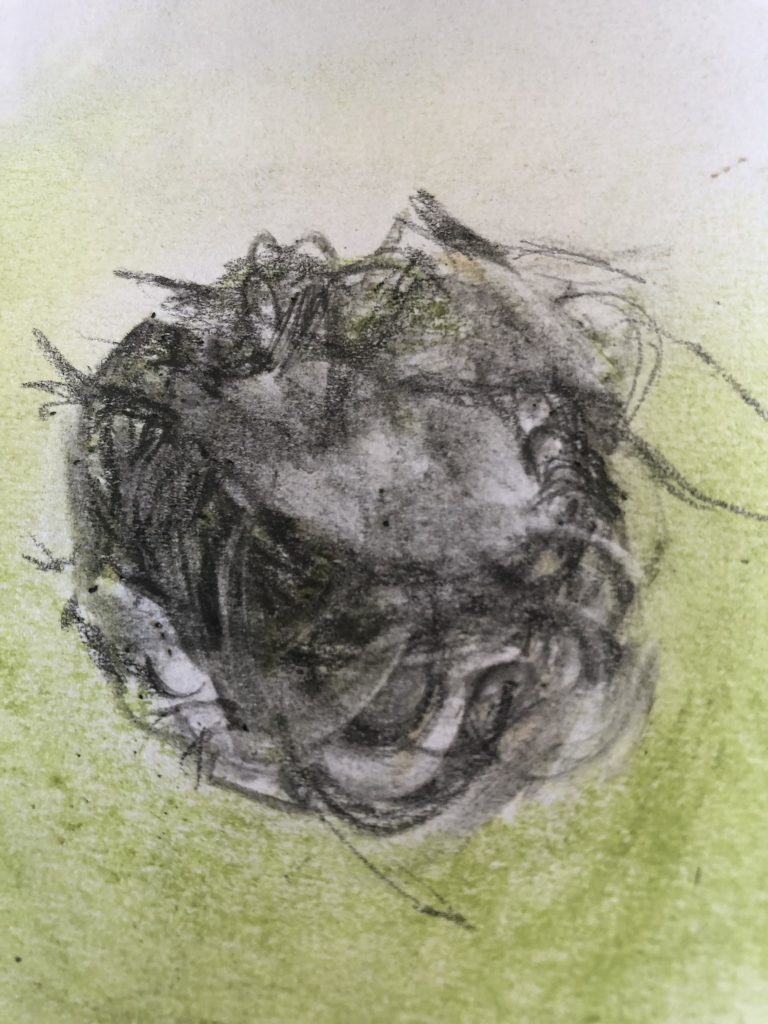

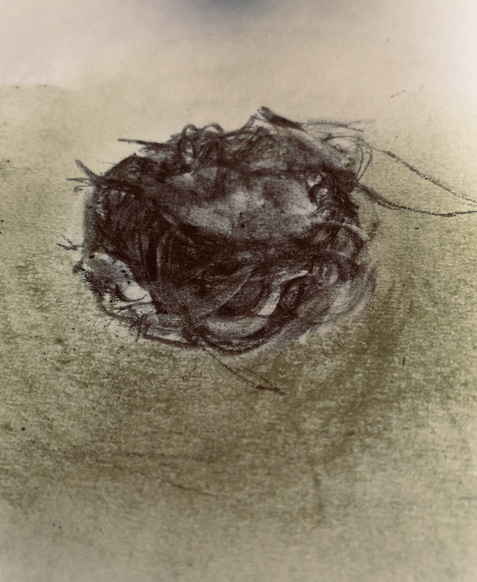

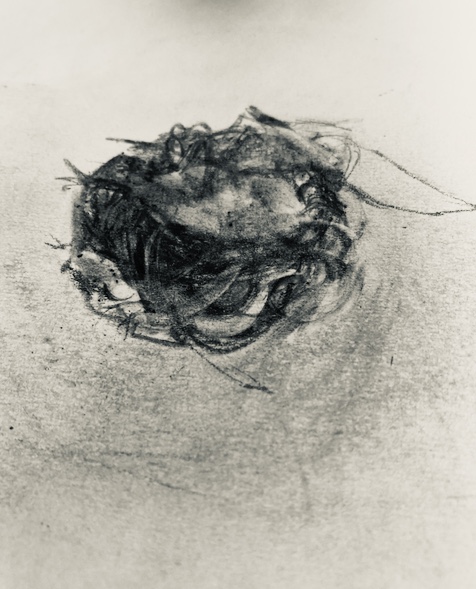

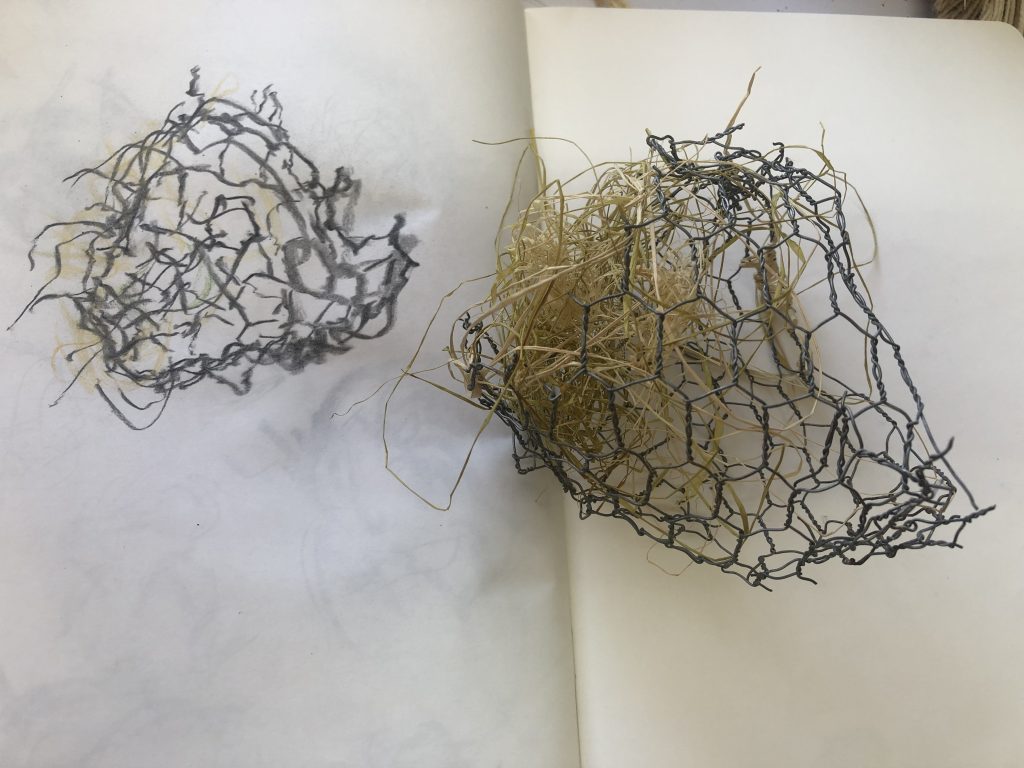

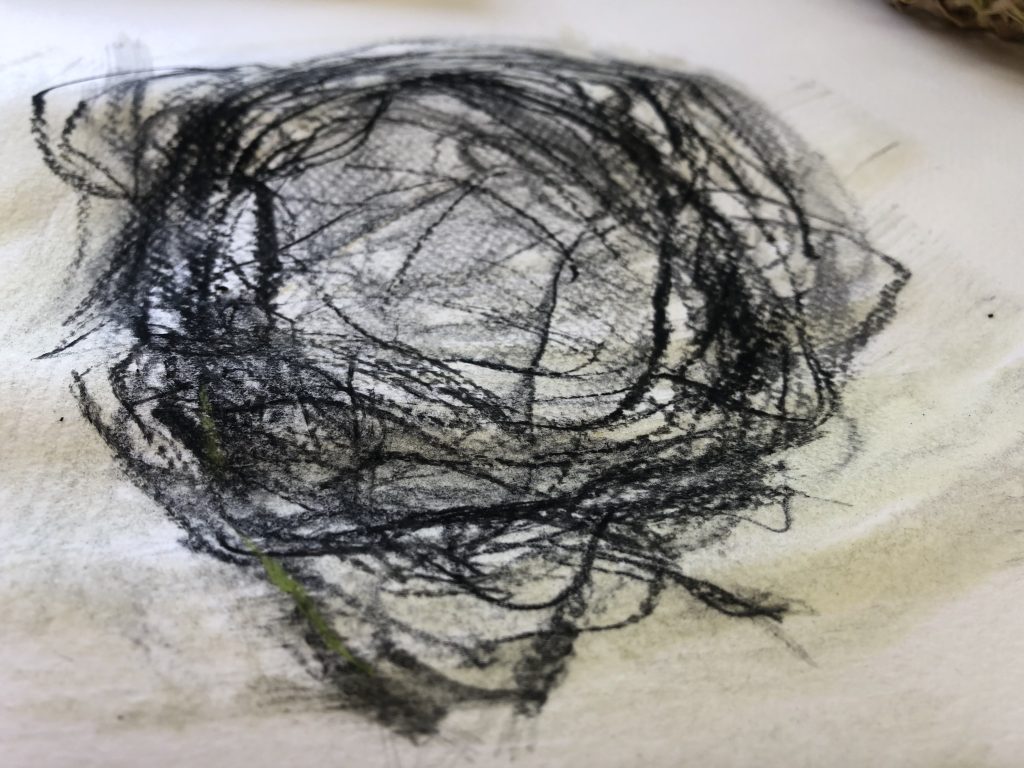

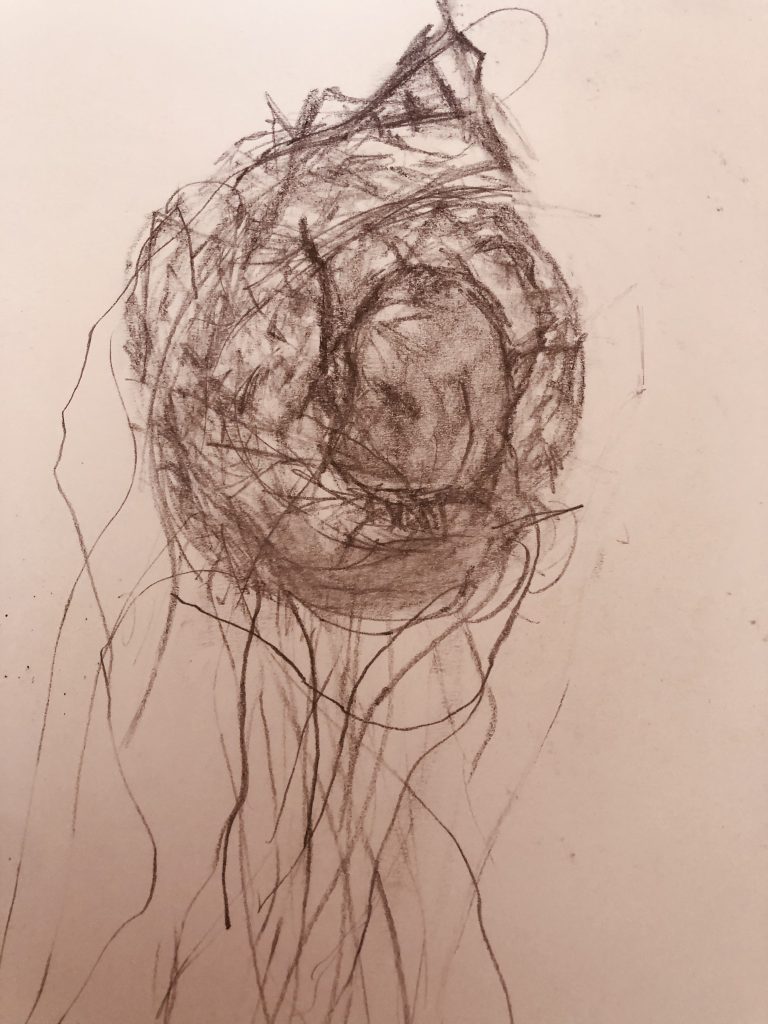

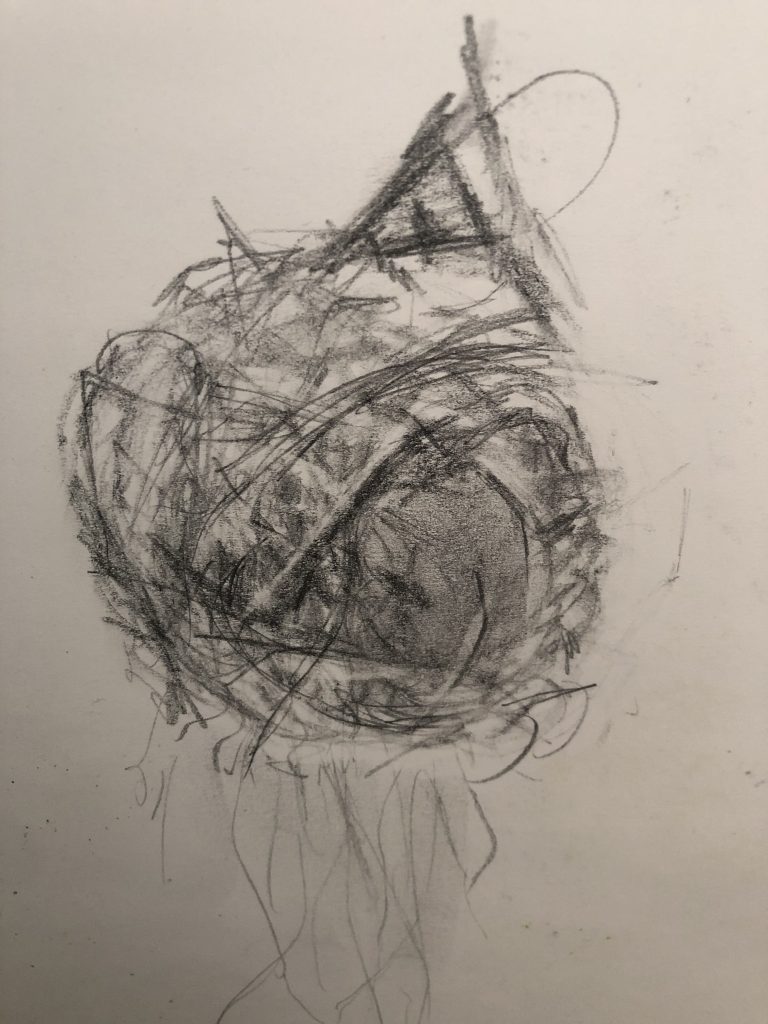

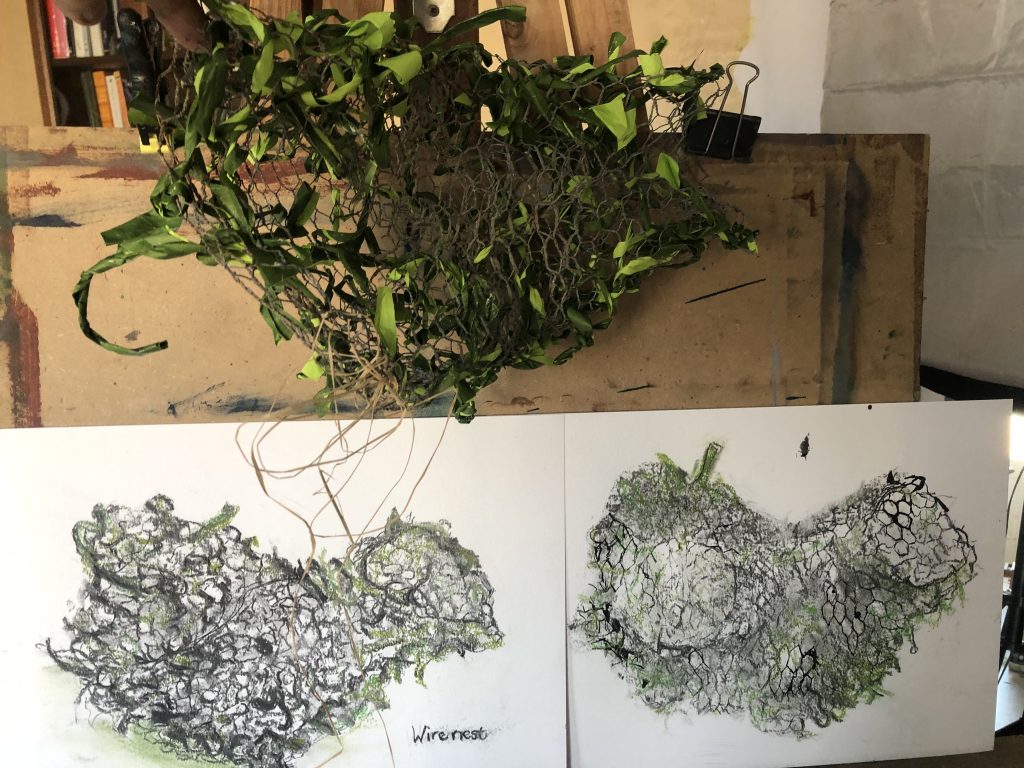

Below is work developing by exploring a nest. The first drawing was in my sketchbook, and I added some feathers. I then started the drawing on archival paper with charcoal. I used an image I made – by taking the nest with other grass and making a photocopy of this assemblage. I considered bringing work into the studio and working with it in this space, considering if the work belongs outside. I am sure these are the thoughts that, during my making, helped me to consider making my nests bigger and placing them out in nature. For my practice of making and exploring nests, I need to develop my understanding of how to create and stay with the aesthetic exploration, and this relies on collaborative capabilities and what Dunnigan refers to as ‘consciously renouncing craft stereotypes’. I need knowledge of technical craftsmanship and will consult to discuss my ideas. When working with industrial materials, such as mild steel, it is important. to consider the impact of the materials over time.

Current work inside the studio

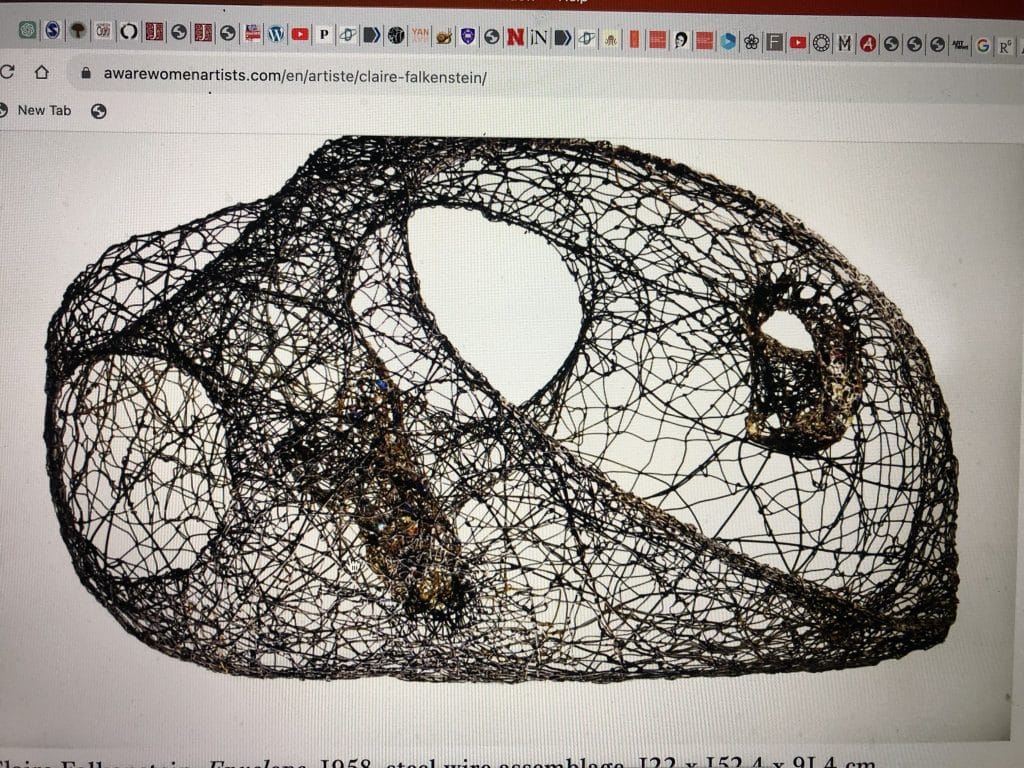

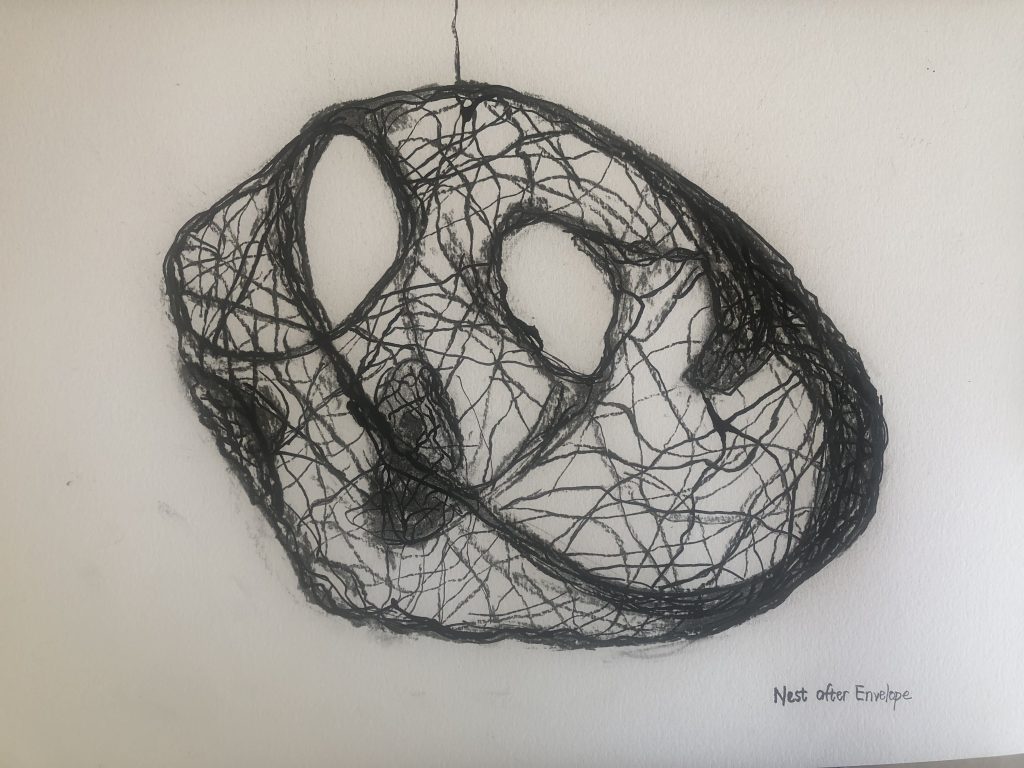

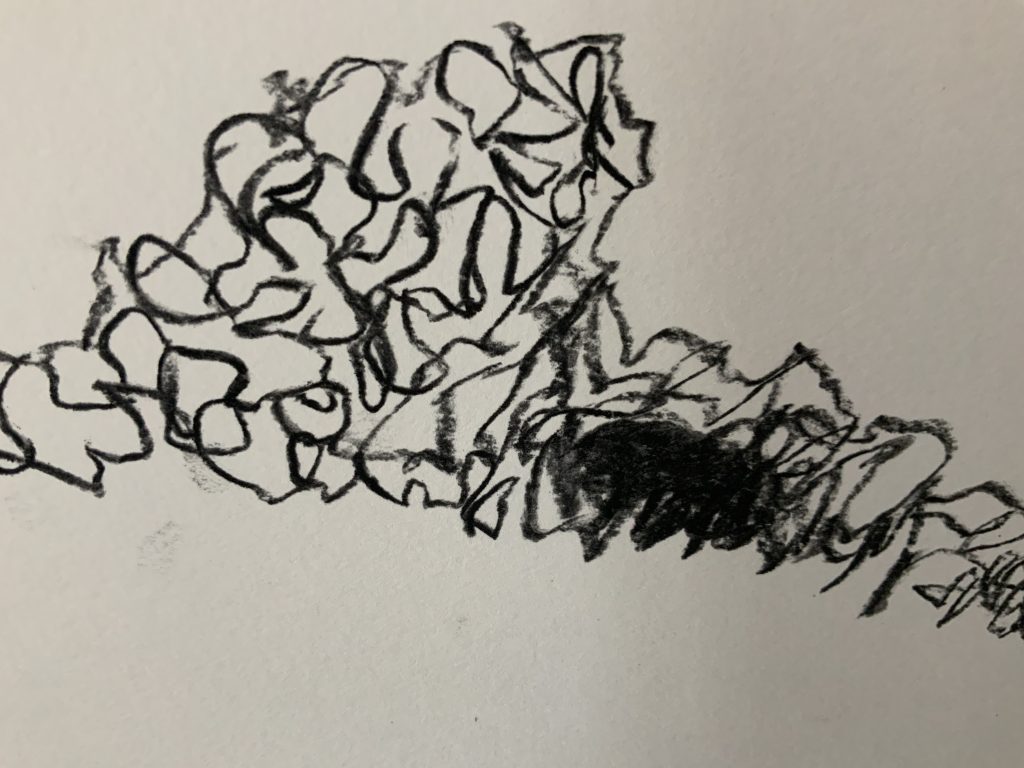

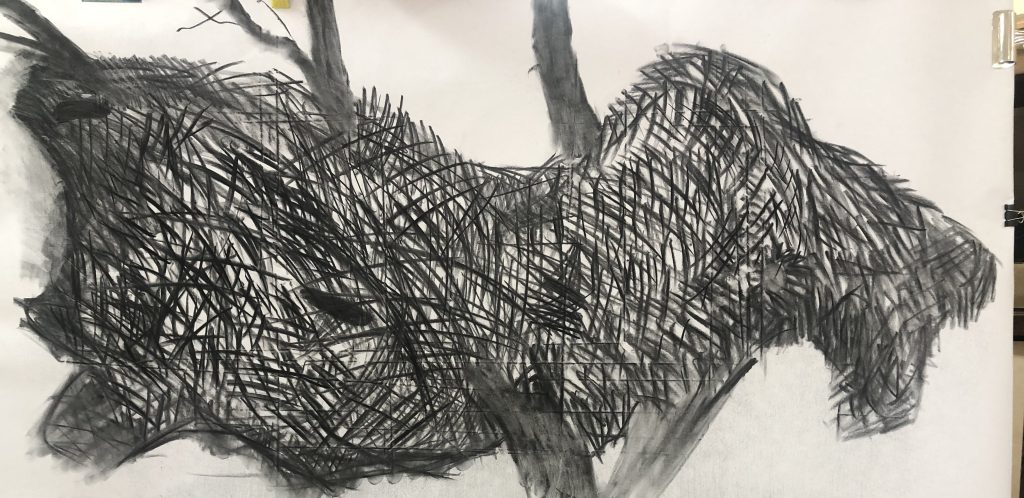

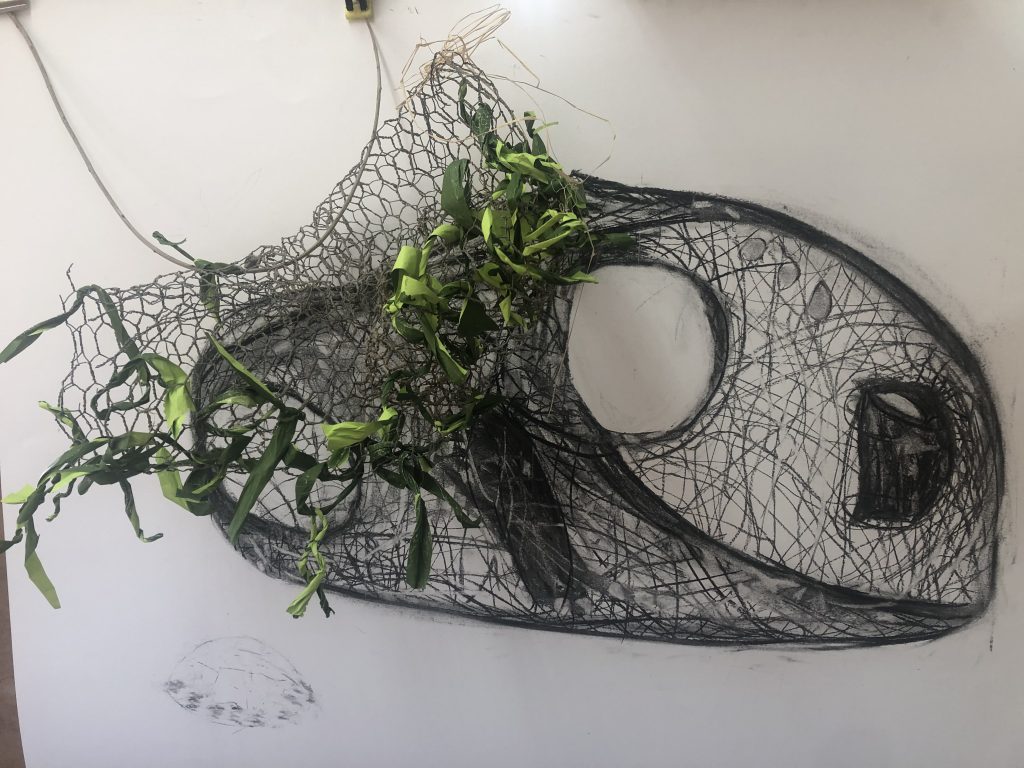

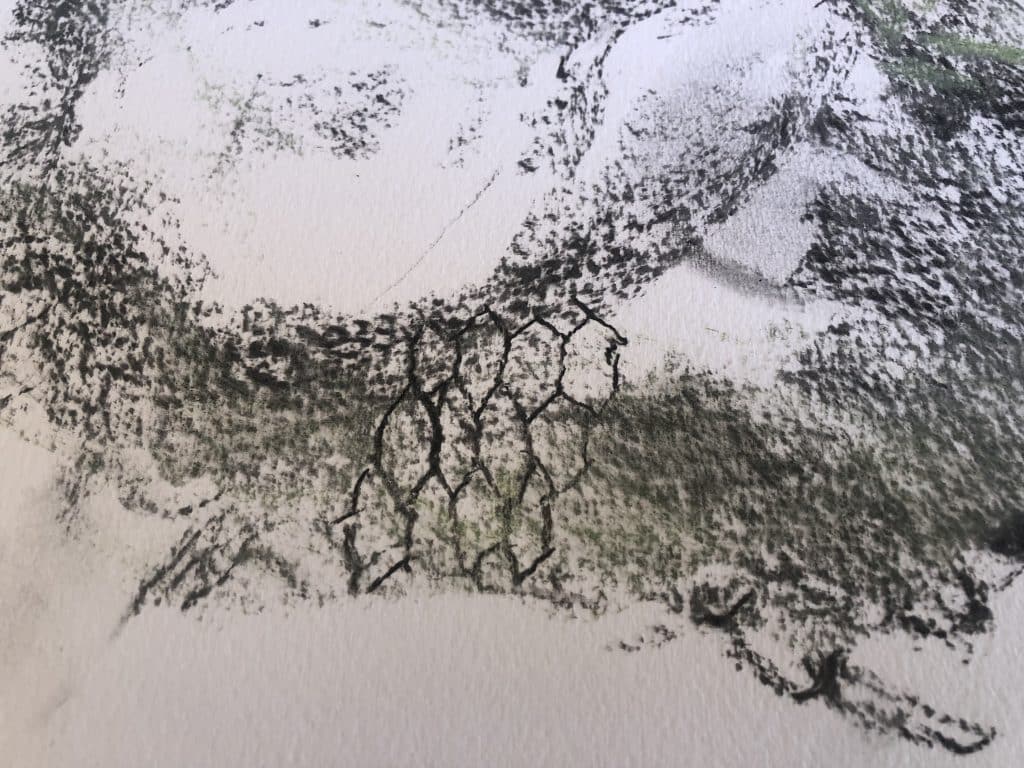

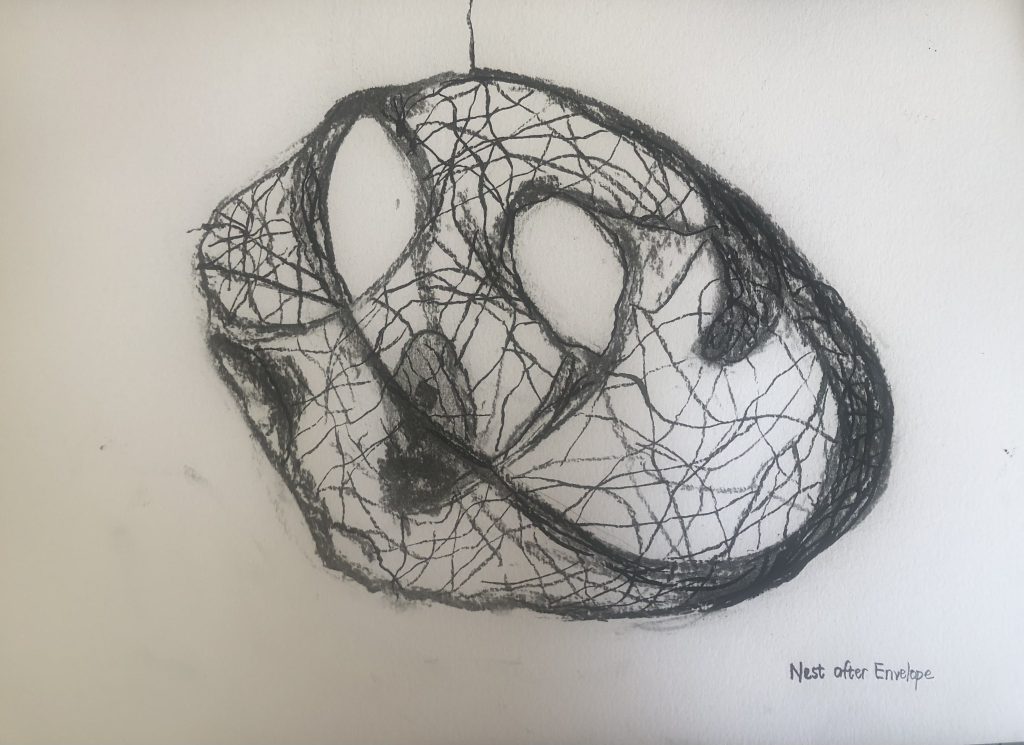

While drawing and working with nests, I copied a work by Claire Falkenstein, Envelope. I want to explore why this work caught my interest and how it fits with my body of work. This drawing was made with charcoal. I love to use charcoal as I can erase, work over or into it and experience the tactility of the material, almost as the weaving of the wire. The drawings are full of imperfections – I cannot capture reality in my making. I wish I could stand in front of this work, touch it and walk around it. I had the opportunity to share it with a group of students in a silent crit, which motivated further exploration.

- the quality of the marks reminds of weaving,

- hollow shape – something inside the circle

- it looks like a giant nest we could stay in,

- Remind of elements known/seen in my work ,

- reminds of Essa Hesse’s drawings,

- and Claire Falkenstein’s wire sculptures.

- Looks like a (pitbull) muzzle,

- or animal skull,

- or a girdle

- or a house.

I continued this process by working with some positive provocations to free up my ideas. I wrote instructions for what I was making.

- Use any found material, think about that shape in space,

- continue to explore the form,

- and draw into the form,

- do you want to explore the form more,

- do you have old work you could explore in terms of this shape,

- fold it

- do you find areas in the shape/form to explore further?

I wanted to research how Claire Falkenstein made her wire works. Envelope, 1958 pulled me towards the 3d shape. She called her wire sculptures “drawings in space.” I to like to think that manipulating the wire can feel like drawing – exploring form and even connectedness. In her body of work, she used themes of scientific concepts and referred to her work’s “Einsteinian” aspects in a seeming effort to evoke interconnected infinity and eternity. I like that the shape or form becomes the connecting idea, part of my making. Her work, Envelope, created from wire and hanging in mid-air, reminded me of a drawing. I read that she intended this piece to be seen from all sides – I can only imagine that one has an experience of the form changing as you move around it – I see outlines (reminds of drawing) and think about how she defines space in this work through hanging it. The form is organic and reminds me of a nest or a cocoon of a larva. I enjoy how it challenges the solid form of traditional sculpture. I think the strongest pull to the work is this seemingly formlessness, or so open for interpretation, but clearly shows an intention to make the viewer think about how this came about – a product of the making process, rather than it being pre-conceived or appropriated. When I look at my nests, I see the connection in this making process – almost evolved into…

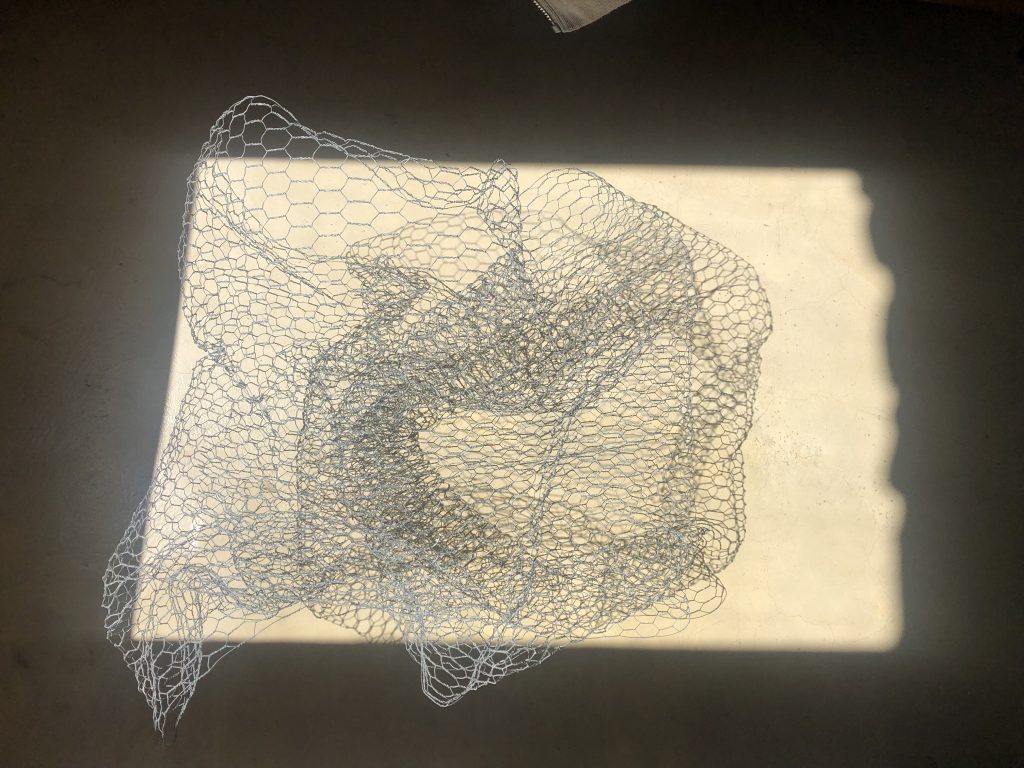

I started with raffia and taped it onto paper; I then drew into the shape – finding a different angle of the same form, I bent / manipulate the wire into the form. I feel more confident now to create a more oversized profile. I would prefer to work with rattan/reeds instead of wire – I think it is easier to fold and a more sustainable option- but I will be open to what I can find and explore this idea. Looking at the explorations below, I see drawings in space with different materials.

Materials to consider from this exploration: wire (found on the farm/collected from) rope, raffia, rattan, ivy vine/plant materials, grass, and collected wool (shearing rejects). I could also make my own cordage (cord from plant materials). I have set out on a search to find more of these materials. I plan to make a small maquette and upscale it to human size. I need advice in terms of the construction. I visited a friend who is an engineer and designer and we discussed materials and making. He suggested I use mild steel rods of not more than 8mm thick to create my framework and start working in the landscape. I can ‘draw’ out the shape on the soil, and ‘hammer in’ some steel rods to act as a rough drawing/shape of the work. I will then start putting the mild steel rods first by manipulating the shapes around the shape and connecting them with wire. I like the idea of having a haptic experience and working with my hands. I also started to wonder about my nest idea as a form of ‘dwelling space’ – of something transitionary.

As I considered the materials, I decided to work with as little steel as possible and try to employ reed or rattan. I think strength is holding a human body, an average of 90kg inside the form. I can enforce with steel and use it to support the structure in the ground. This gives me more room to explore other materials in terms of design and making. I prefer to work with found and natural materials as it carries my empathy for nonhuman species and actions of care and repair around nature.

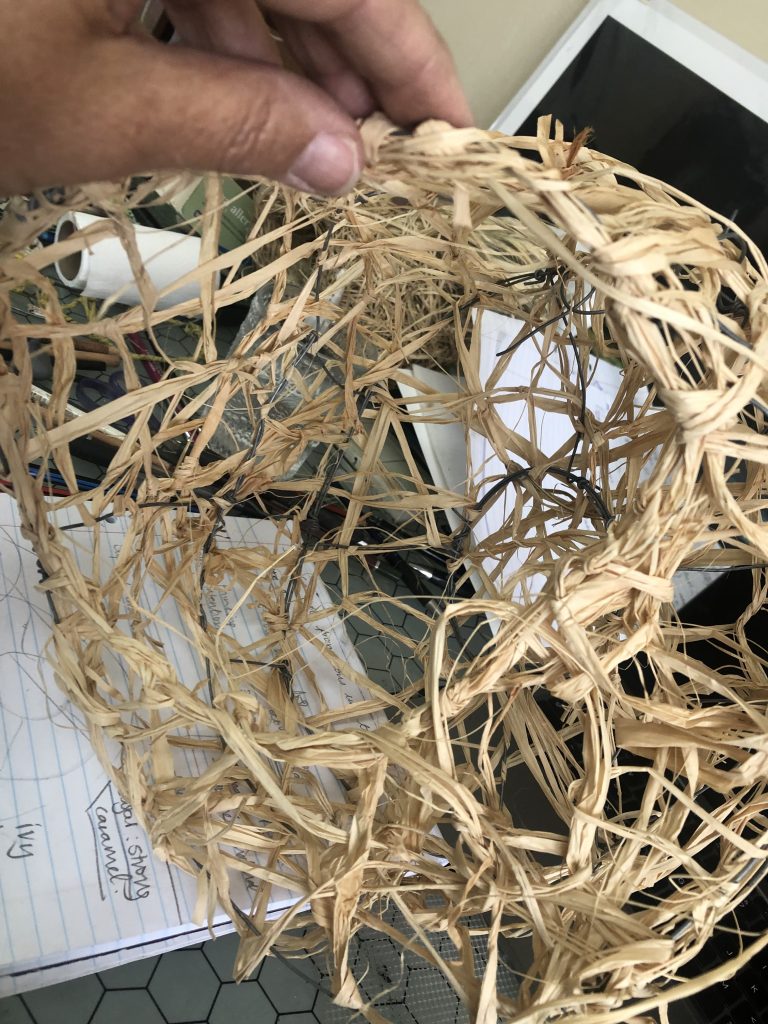

Other makings from a practice day where we worked with provocations -the making happened inside the studio where I used an old work, wire construction and wove the raffia into it to form a nest. The wire is malleable to manipulate the form and I can add more weaving layers to create a dense nest. I like its transparency at this phase in the making and am content not to continue to make it thicker and more nestlike. I do think it sits nicely in the space outside and find it a good place to take the work. On the Tate website, when I researched the work of Maria Bartuzova, I read that she in the later part of her career began to place her works in the trees in her garden, where she then photographed them:

‘I would also like to realise more things directly outside – to connect, to merge my work in the work of nature organically.’ (Tate https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/maria-bartuszova/five-things-to-know-about-maria-bartuszov%C3%A1s-unique-sculptures.

PROJECT 1b: Taking Stock

Appraisal and evaluation are suggested to take stock of my developing body of work to identify gaps or areas that could still be developed. As I have been working on the first draft and second draft of my Research, I am looking at my work and finding connections with my writing, as well as kinships between some of the works. In our previous tutorial my tutor suggested I state my position in my work and my theoretical approach – it needs to become focussed.

Doing more research on how Falkenstein made Envelope, 1958 (This can be viewed as a separate blog: https://karenstanderart.co.za/claire-falkenstein/)

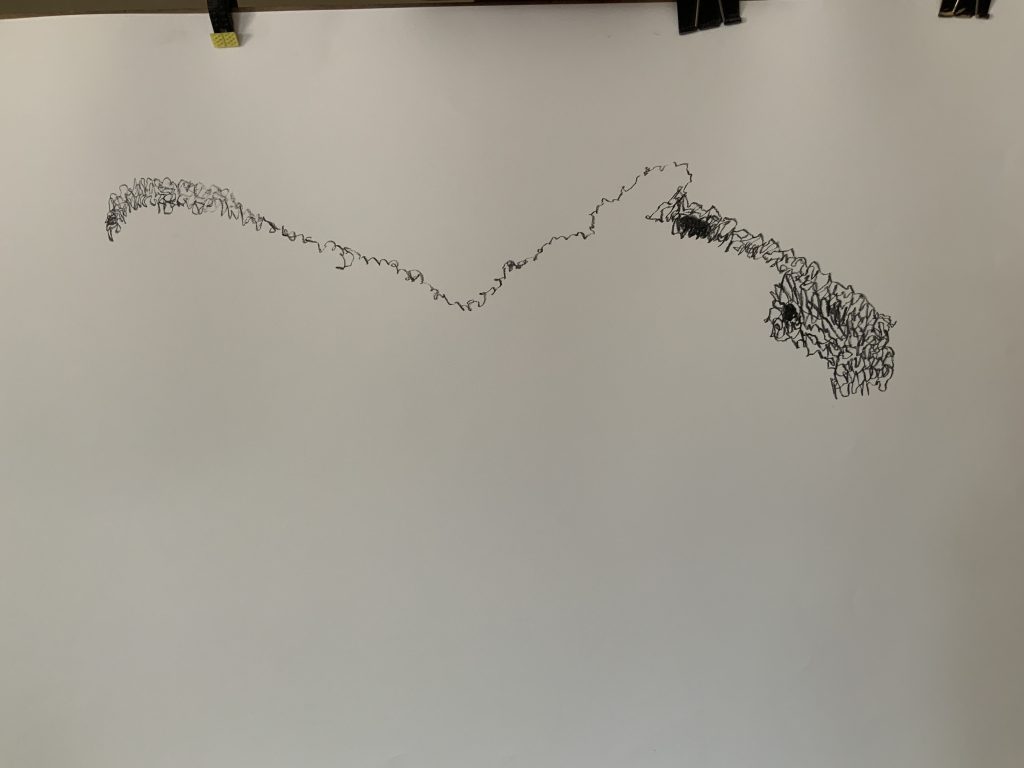

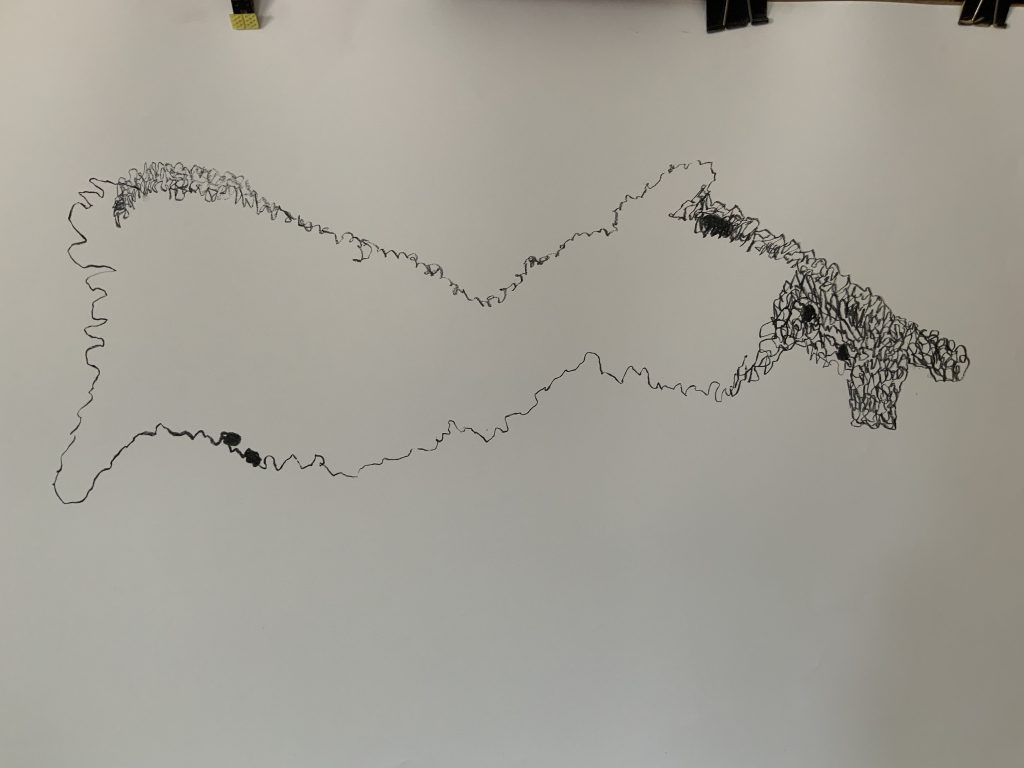

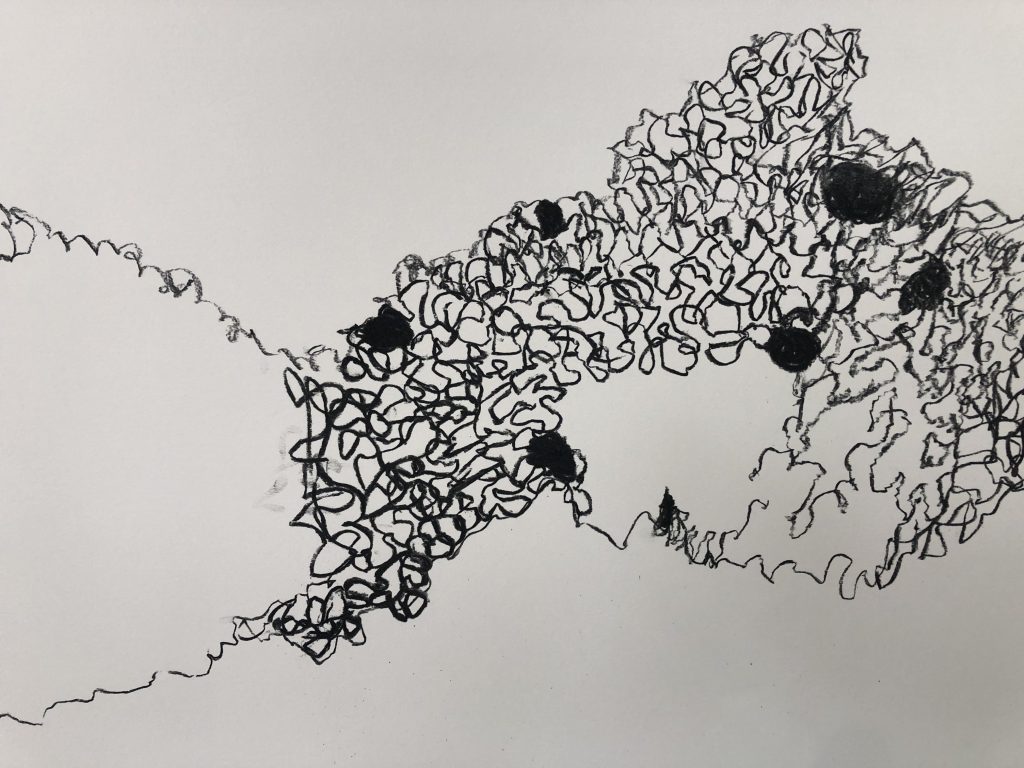

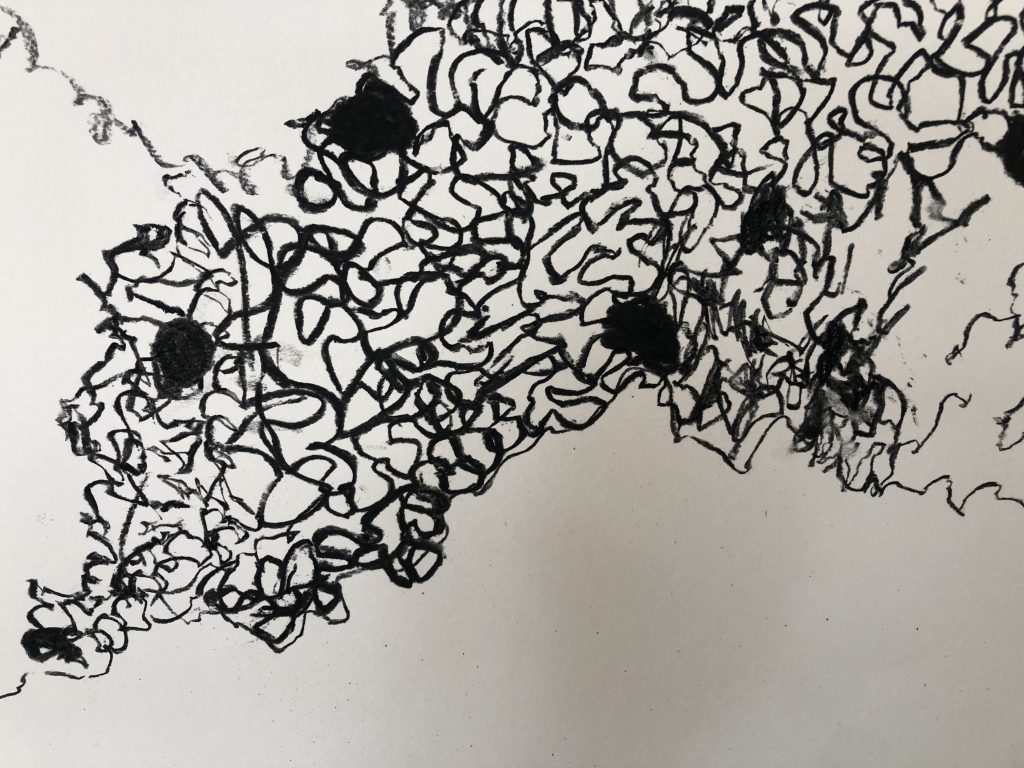

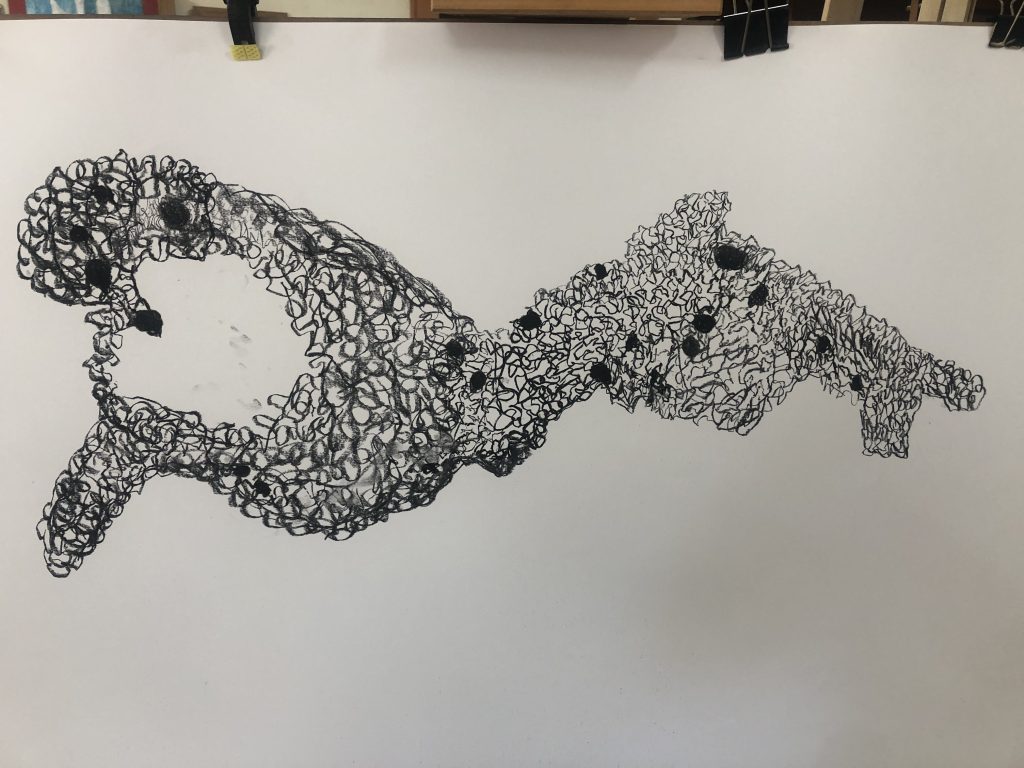

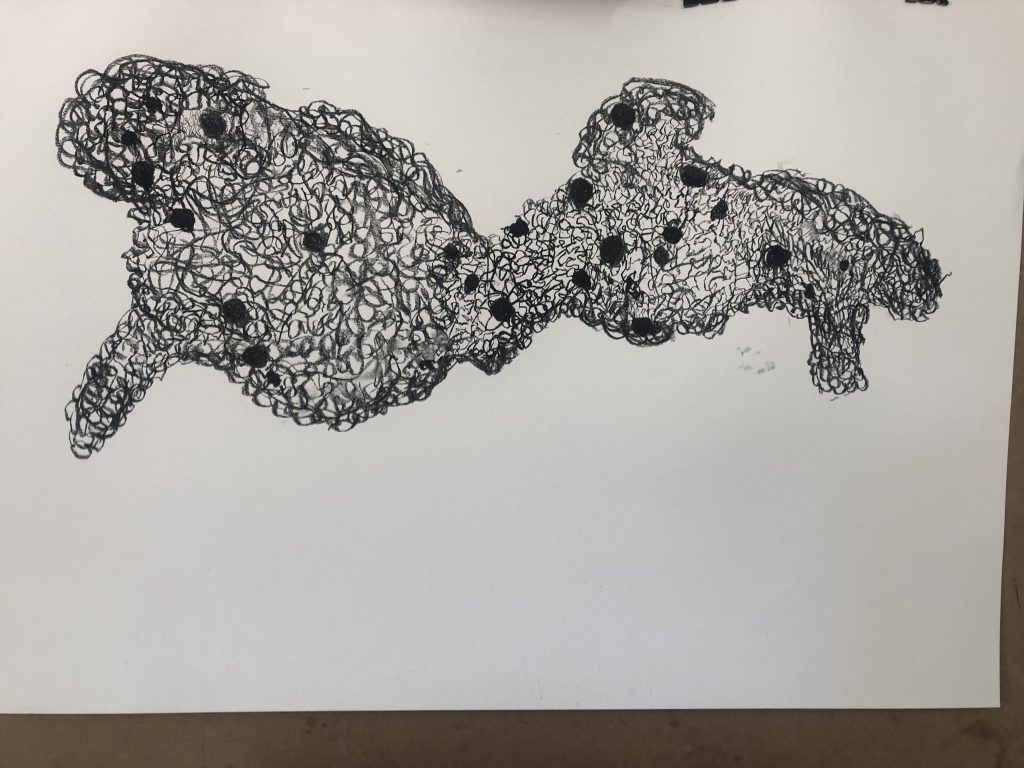

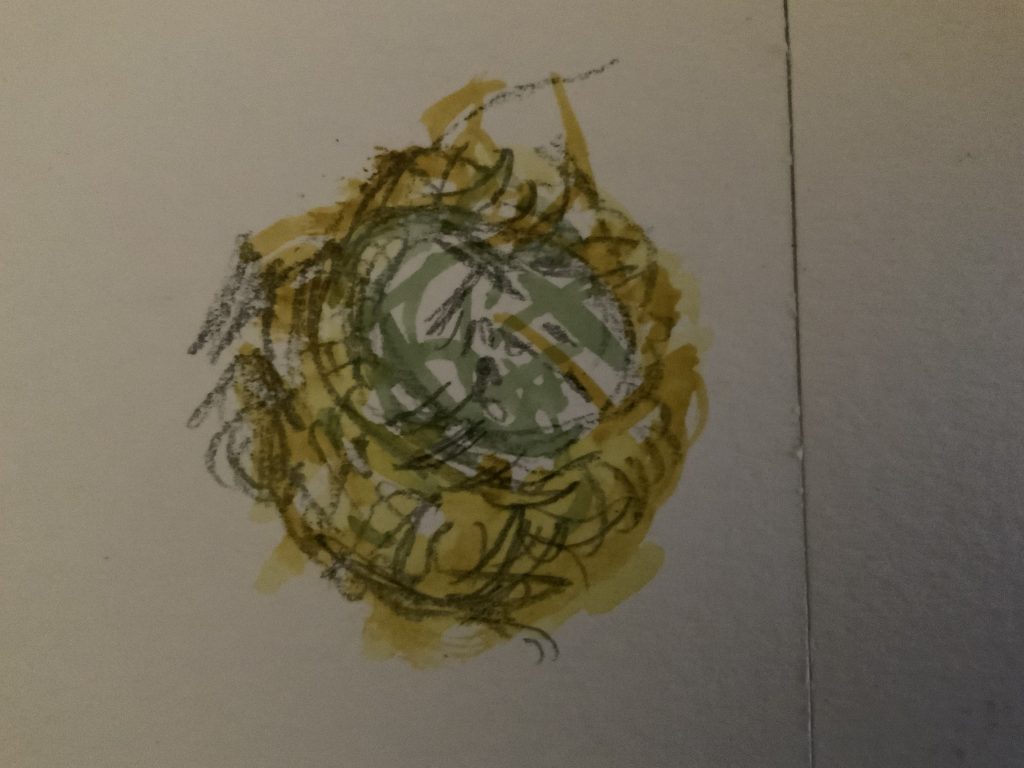

I decided to explore another nest drawing – using rules. I could only work with one medium, draw with continuous lines (which reminds me of weaving)and time the process. I used a found image of a sociable weaver nest. These vast nests strongly influence my making as I see the potential for drawing and more development of form, volume, using negative space, upscaling and using different materials.

Instructions:

- Work with only one medium

- I keep my drawing medium on the surface and not lift from the drawing during the making process.

- Time the making sessions.

- I will take a photo when I finish each section.

- I opt for a new rule – challenge my making by working with both hands.

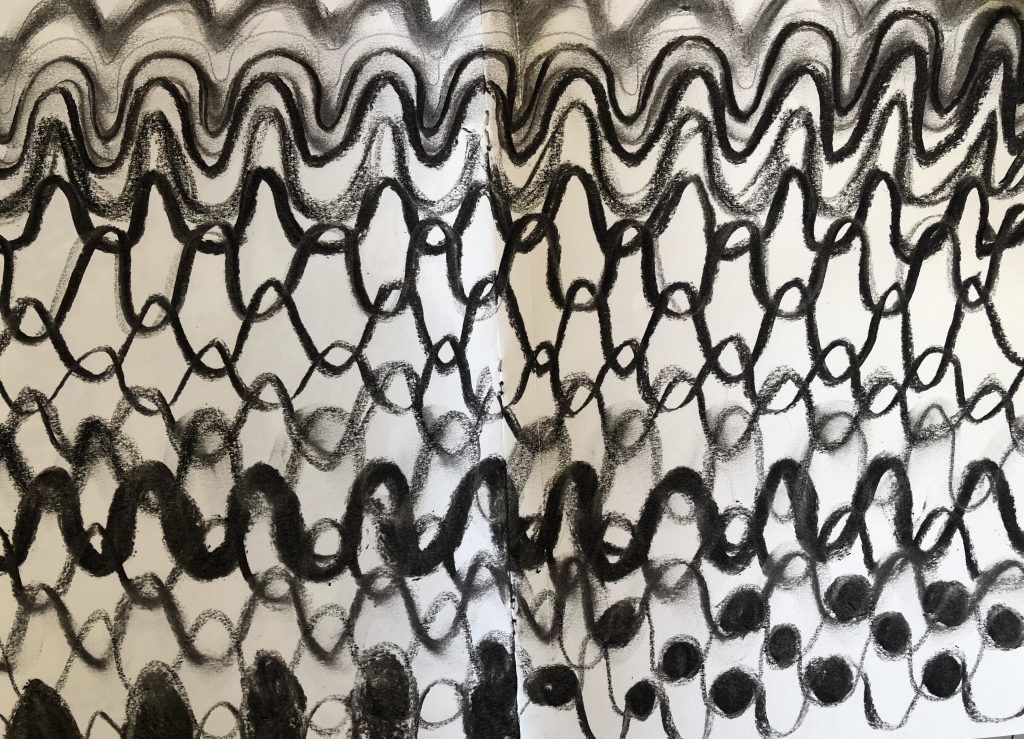

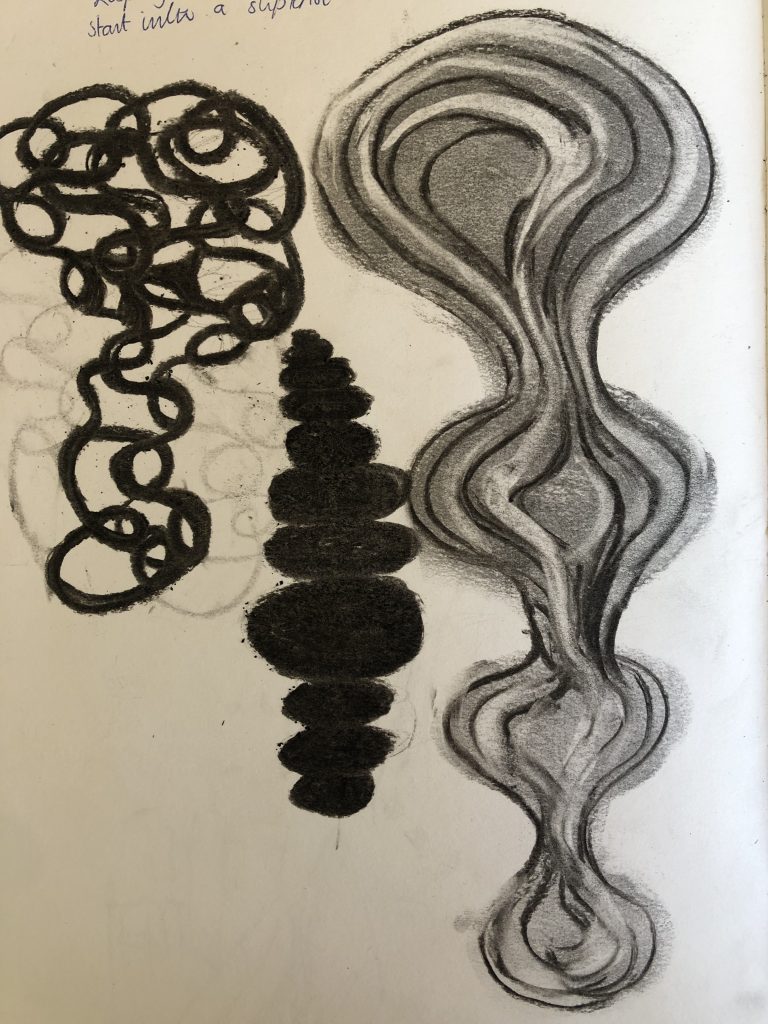

It started again at 13:35 and continued until 13:40 – my hand felt the movement and got tired of the continuous turning. I wonder if I could continue for more than 5 minutes at a time. Add another rule: work in sections at 5 minutes at a time and write immediately about the experience. The movement is between my thumb and index finger – holding and rolling the charcoal over the paper’s surface. Looking at the marks is reminiscent of tiny squiggles and marks left. I does remind me of wire – although the weaving is not quite there, it is a loose drawing. I find it extremely difficult to control the charcoal and see my Right-hand tires. I experience being uncomfortable and having to focus on the line/mark-making. I do manage to do work for 4 minutes till a piece of charcoal breaks and stops my flow.

At this stage, the form seems like a nest I could add as a 3d creation and place it outside. I have to contemplate materials, but I like the organic shape. I am glad this drawing experience kept me within work and opened new ways of looking and making. I am thinking of a cut out of this drawing to free it from the paper and take it outside. In real life, these huge nests look like thatched roofs as they weigh down the dry branches of the Camelthorn trees.

I made more drawings (without rules) and tried to follow the form and explore the marks in the nest. I agree that with every line I drew and crossing another over it, I made an aesthetic decision regarding how the drawing would look. I am reminded that in drawing, I can erase whilst making choices about the type of lines. This reminds me of weaving and making these decisions to create a desired form and opens up the choice of material one has to know about and access to acquire the correct or most suitable material.

When I consider natural material, I find it good to learn from the making of P Dougherty. I viewed videos where he talked about his making and showed this working with wood saplings to create structures. He spoke of his making process as “…. to transform a backyard material into something that has credibility..” (Video clip: Stickbuilt below) I learned that he works mostly intuitively and does not necessarily follow his initial plan/drawings – I guess this is his experience with materials and making offers. I found it interesting that he said his sculptures last about two years. I thought it would last longer. The nests of the sociable weavers last for decades and generations in harsh conditions. In the Kalahari where these nests are found, the day temperature reaches 40 degrees Celcius regularly during summer.

I made smaller sketchbook drawings to consider colour and how these flat forms can be developed as upscaled 3d objects. I see them as quiet works, which sit with the smaller nests I have made and tell a story of fragility, softness, and tenderness, which I think drawing can translate well.

I realised over time that charcoal is always my first choice of material – I enjoy that I can create layers, invert objects, erase and create a memory of making which is always seeable for the viewer. I enjoy how the process of making is shared in these smudges as a history of making as well as the passing of time in this way. On a personal level dealing with death it reminds me that one can never really erase the past and the importance of memories.

Should I consider other materials to make with – twigs? I also contemplate whether the work should be outside or in a studio. My tutor suggested I look at the work of Kate McDonnell, a processed-based artist. The works below were done with twisted paper. She seems to twist the piece in on itself, going tighter and tighter until it forms a chaotic mess. This continues as a repetitive action and is then used as a cascading installation. I read she used black tablecloth paper – the work reflected on anxiety experienced during the Covid epidemic. Thinking about how she twist paper into almost tortured garlands, one becomes aware of a process which embodies wasted time, or pointless labour, but also a way to deal with emotional issues like regret, shame, pain. It was described as a cycle of redacting, tearing, twisting, crushing and erasing.

I wonder about using hair and wool – (plaited and frizzy) yarn, twigs, mud, clay, straw.

I like considering what Petra Lange-Berndt suggests in Documents of Contemporary Art: Materiality: ‘…to follow the material means to enter a true maze of meanings’. In this way, the form of the nest and its material can be explored with the twisted paper as a sculpture form. Newsprint, recycled paper, shredded paper, tissue paper – it reminds us of the nests being collected or gathered from the immediate area, temporary, fragile, and could burn.

Curator Nicola Turner says: “Materials – the stuff that artists work with – have become a way of loading artworks with meaning, and each artist in this exhibition holds the stuff they work with at the heart of their critically-engaged practice.” In Documents of Contemporary Art: Materiality, Petra Lange-Berndt says, ‘ To follow the material means to enter a true maze of meanings’. By leaning on materials’ political, social and psychological interpretations, artists allow their chosen materials to discuss broader issues. In these works, form becomes the servant of the materials. (https://www.nicolaturner.art/about-1)

I decided to start making a nest with twisted found paper. I am using wrapping paper. I cut it into strips and began turning the paper. I found after a while that working with short and thinner strips of paper is more accessible. It is a time-consuming and monotonous task, and I wonder if I can use a tool to assist in the making. I was a passenger in the car driving from our farm to the city – 45 minutes and decided it would be a good way of starting this project. I will record my process to show the documentation of the making. I am considering the material as a carrier of history – flowers as a gift for my birthday were wrapped in it, and now I can re-use it to make a nest and consider the interconnectedness between things. It made me think of the material as in a way being ‘worthless’ but now ‘becoming’ something different. Twisting and almost overworking the paper is a repetitive working method reminding of

I first used a form by bending wire, which reminds me of Falkenstein’s work. Pulling the paper through the wire is time-consuming and one can manipulate the wire. I am more aware of the experience of making these works, and not so concerned with how they will stand in time – the wire can be easily manipulated, will rust over time and I would like to watch it decay. I am concerned however with the paper I used and need to reconsider its use for outside work.

In the exercise, of the above drawing I explored the sense of touch and and worked blindfolded.. I later explored this as a drawing with charcoal and pastels after a drawing exercise as part of the OCA Big Draw, which I found on their shared padlet.

Making these drawings reminded me that my drawings are ways to understand touch, texture and materials I can explore.

Below is a work reminding of giant amoebae, or cocoon, which was made in 1956 by Falkenstein. The work and material show varying densities and how the artist continued experimenting with volume and space. I like the hollow areas folding into the piece – it reminds me of voids, a quiet space to sit in, and looking in and out. The work emphasises the space within and shares the openness.

I will continue to explore the form of Falkenstein’s wire work as nests and continue to make drawings. The more I look at this view of the drawing, the more I see a nest that could hang outside in nature. The shape also reminds me of a chair. I am aware that these images touch my sense of feeling safe and comforted. It is as if it lets me take steps towards a space where I acknowledge a need to feel comforted and take time out, being alone with myself, but feeling embraced and inside a safe circle.

I found a thought-provoking nest made by Tadashi Kawamata, called ‘Nest in Liaigre’, 2023. This site-specific installation questions how we interact with our built environments. The chairs remind me of a weaving process, and they sit to the outside and wind inside into a Paris studio. I like how it sprawls into the building as well as his house of vintage chairs as material to make with.

This work made me consider where I want to build a nest outside – I am looking at the area outside my studio, where I can make use of the veranda structure to hang a huge ‘social weaver nest’. I like that it is just outside my studio and that I can work with a current design. A wind storm has recently caused some structural damage to the cement pillars, which we need to repair. I

The nest below was made in nature whilst on a camping trip and sitting outside, listening to the sounds of birds around me. I worked with ivy twine for the frame and used raffia for the nest. I wanted to stay with the structure of Frankenstein’s Involuting Zero, and consider a nest reminding me of nature’s gregarious, sociable weaver nests. I think about collective efforts when constructing their nest and how these birds live in a tight-knit community. The nest becomes more than a home/safe place; it also talks about the beauty of collaborative attempts shown in the natural world and how interdependence brings me back to my questions about connection. In the making of nests I still find a lot of exploring and learning happening and I am not to concerned about perfect outcomes. I am learning more about the natural landscape and the caring that goes with that when one makes art about this experience. I can use my imagination when I explore. I am now more comfortable with using ivy instead of metal/wire for the structure and forms I can create.

i see a kinship between the wire structures of Falkenstein and the sociable weaver’s nests I want to create. The possibility of

Considering the nests of the Sociable weavers

Looking at the nests of the sociable weavers who have captured my attention in nature, I learn that these nests are not woven – they are made of different plant materials stacked to create this unique structure, which almost reminds me of thatched roofs. These large compound community nests are a rarity among birds. The nests are large enough to house over 100 pairs with their offspring. A sociable weaver bird, Philetairus socius, is a small passerine weighing approximately 27g, and they are endemic to the semi-arid Kalahari and western parts of Southern Africa.

It seems they use mostly Stripagrostis grasses and twigs. The nest consists of at least 250 chambers, which is accessed through an entrance tunnel at the underside of the nest. This makes the internal side of the nests much cooler than the external temperatures during the warm summer season.

Artist I researched: Andy Goldsworthy

This artist is best known for his small ephemeral works he created in the landscape and recorded as photographs. (Hand to Earth, 1990:125) In the chapter of this book, Environmental Sculptures, Andrew Causey (1990:125-141) shares the making process and good images of work done by Goldsworthy. Here, site and size come into play, and as the work is commissioned, the artist also made drawings and brought in assistants and skilled operators for excavations. He preferred to work with natural materials and has used steel, a man-made material, as it shows a life which shows the change in colour and texture over time – rust.

Earlier in his work he made leaf pulps boiled in caustic and beaten with a stone to loosen the fibres, which was washed and moulded for some of his work. As it dries, it takes the desired shape, but one still sees the inner and outer structure of the materials. The materials he used: Birch bark, twigs, bracken, iris leaves, plane leaves and stalks, pine needles, horse hair

Simultaneously, Severijns has been working this year (2017) on a “Nesting Series”, the logical continuation of rebuilding ones “nest” (home) after being uprooted or displaced. The artworks focus on paper texture and abstract compositions that are inspired by the nature of her new homeland. She is especially intrigued by the cycle point at which there is total bareness, vulnerability, decay, and disintegration. These elements and an abandoned bird nest that the artist found laying on her street inspired her to give life to paper nesting vessels, that explore the 3D effect and push the limits of paper. These five Nesting Vessels are symbolizing the power of displaced people (re)building ones ‘home.

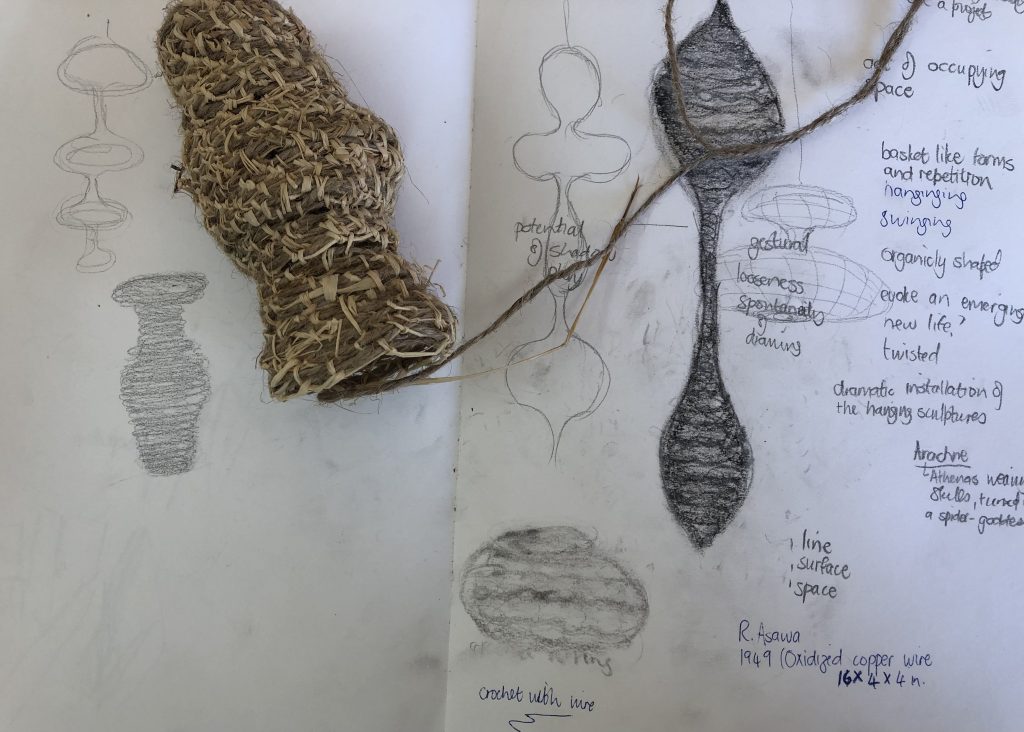

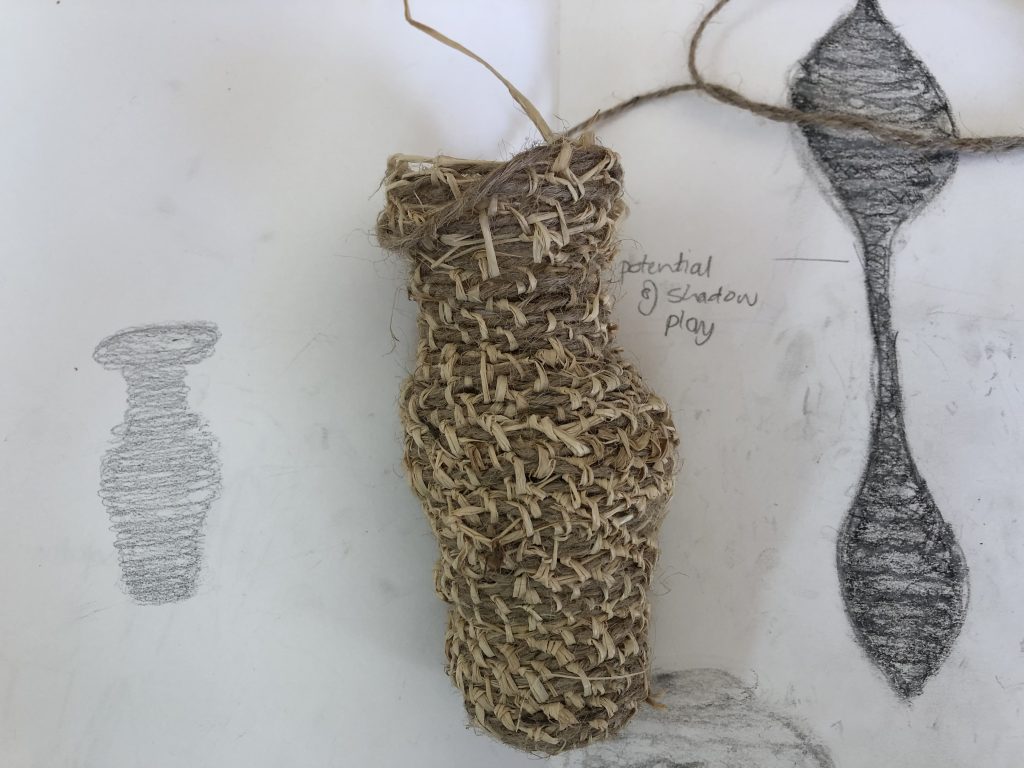

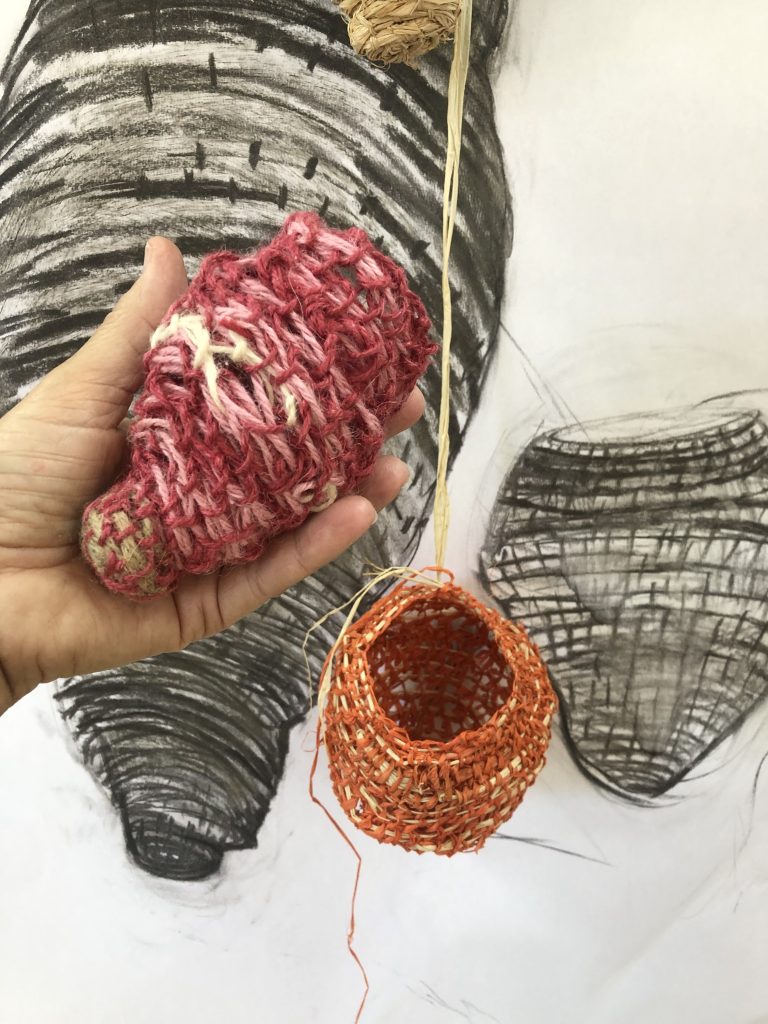

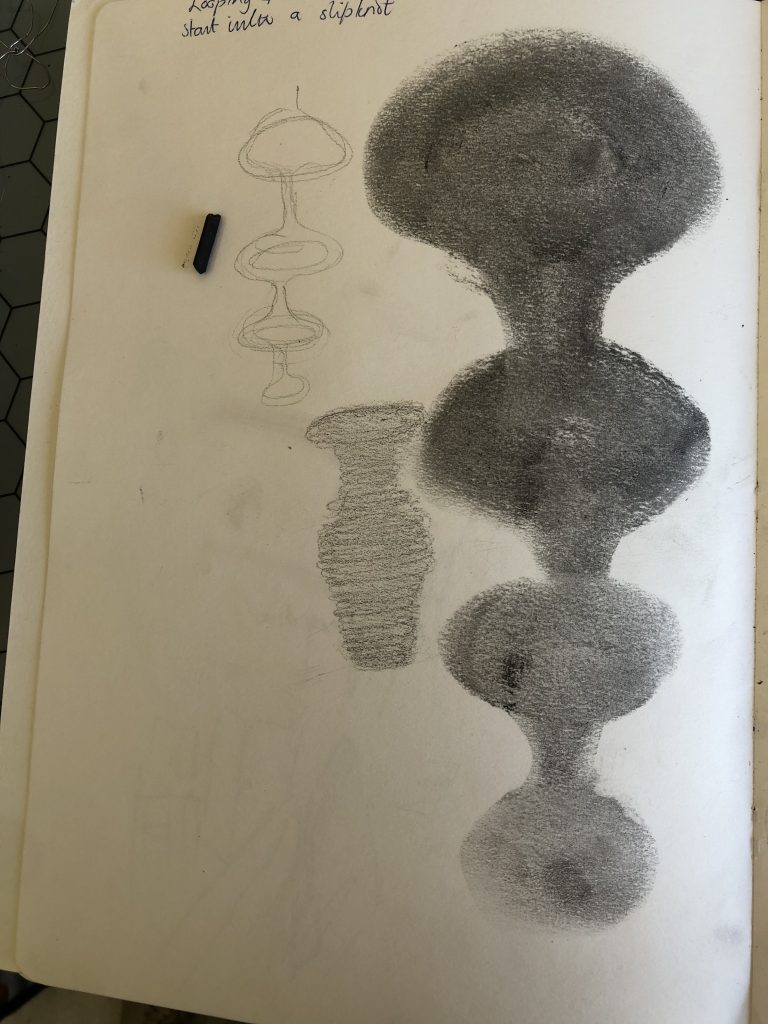

I was also drawn to the work of Ruth Asawa as I continued exploring basketmaking and weaving techniques for making forms.

I looked into learning the looping techniques of her making.

I consider how her work occupies space – how shadows become another feature in her work as hanging or swinging objects. I find the connection with nests hanging and the organic shapes of her works.

I became interested in looking a the looping technique she apparantly learned from Mexican (egg) basket makers. I like that these works can be translated as gestural drawings, that they are loose and full of spontaneity. A higlight of my learning from Asawa I have to mention her personal choice of living her life as an artist, that the work one does, should be meaningful to your purpose in life, its about the art of living well. (almost finding the aesthetic possibilities of the everyday). She had a prolific life of making/creating, and that is very inspiring to me.

Bibliography

Asawa Ruth