This blog will be shared for the Assessment (Feb 2024) with the assessors as a referral to the Learning Outcomes.

Fine Art 3: Advanced Practice (FA6APR)

- LO1 demonstrate a comprehensive knowledge and technical and practical skills through your work

- LO2 produce an ambitious body of work that is critically informed

- LO3 demonstrate how experimentation has informed your practice and visual language

- LO4 articulate your critical and conceptual knowledge and understanding of a range of fine art and contemporary contexts

As my Body of Work developed, I wanted to consider the nests and objects as making hanging sculptures. For this writing, I researched artists concerning my making practice and hope to synthesise and evaluate their work. This blog was written alongside my making and research. I have added new ideas and works as I progressed in this course to share my thinking and exploration throughout the course. More options could be to explore the narrative of the materials, consider symbolic significance, sensory explorations, documentary, cross-disciplinary collaborations, curatorial approach and even community engagement, which could add further layers of meaning to my work. I hope to explore this during the last part of my studies (SYP).

Below are works of artists who inspired my material investigations during my nestmaking process. Considering the learning outcomes for FA6APR, my tutor suggested I write more about how my work was informed whilst I was researching other artists’ practices around ideas of nests and connectedness with non-humans. I was also encouraged to bring some critical thinking about this project and the work of others into the framework of my writing. I have blog posts on artists who influenced my making and thinking during in the Research part of this course, as well.

Through this making, I am inspired by the materiality/material questions that came about during my making, such as how to make sense of this push-pull between tangible surfaces and the immaterial that the objects I am making carry/transmit.

Bianca Severjins

This artist made nests during 2017, which for her was the logical continuation of rebuilding one’s “nest”, symbolising a home after being uprooted or displaced. Her work focuses on paper texture, and the nature of her new homeland inspires her almost abstract compositions. She developed her techniques to manipulate paper based on layering, merging and weaving the rough hand-torn paper.

She is especially intrigued by the cycle point of the material at which there is total bareness, vulnerability, decay, and disintegration. She says that finding an abandoned bird nest on her street inspired her to give life to paper nesting vessels that explore the 3D effect and push the limits of paper. Her series of work around nests contains five vessels to symbolise the power of displaced people (re)building one’s home. I learned she was born in the Netherlands and currently works and lives in Israel. It was her choice to uproot from the Netherlands, and she shared that her experiences as a new immigrant creating a home in a new country were the inspirational foundations from which her paper artwork sprouted.

Kate McDonnel

I found this artist on Instagram with installation work displayed in cathedrals in the UK. She finished her MA at Bath Spa University in 2018, and in 2021, she was named an ArtConnect Artist to watch. She works primarily with twisted black paper, which turns the mass into clumps using knots and entanglements. She overworks paper till it becomes a near-destructive material -it seems purposeless and could even be underpinned by shame, regret, or wasted time. The paper starts looking like metal. She uses a ballpoint pen to redact receipts and psychiatrist’s letters. Heaps of crushed tissue paper will crawl up walls in her installations, and clothes are tightly bound with string and thread.

Her practice is firmly rooted in process art and influenced by postminimalist artists such as Richard Serra and Eva Hesse. She also uses her process-based art to explore the topic of mental illness.

I have looked at using paper for constructing nests, and the method of rolling the paper inspired my process when I started rolling cut strips of brown paper and thinking about the sociable weaver birds, nest, as in their making process, they do not weave their nests, but, layer it. Rolling the paper is a time-consuming task, and it reminds me of a bird flying to a tree during nest-making to gather material for the construction. Below is an example of what I made after this research. I see potential in this material to weave and merge pieces. I enjoy the fragility of this work.

Jonathan Baldock

I looked at his work Warm Inside, which relates to nests in that he created human-sized cocoons. When reading more about this work, I learnt that Warm Inside was made during the pandemic, that the artist saw these life-sized cocoons as referring to containers and that they became essential human-made forms that have always been used for collecting necessities for survival – in this case a place of safety and protection during the Covid 19 pandemic.

By dying his materials, spinning the wool and doing basket weaving, he employs techniques that refer to traditional craft methods, which are also time-consuming. I learnt that spending time with the material and processing it to its fibres is essential for the artist. Interestingly, this work was done during the COVID-19 pandemic – time was almost a gift to him, and I think it inspired him to invest in these raft methods. But also opened up thoughts about the preciousness of having a home, a contained space which is safe, but also the contrast, where things could become undone. The artist inscribed himself into an old craft tradition, which is time-consuming but connected with the materials. Listening to a conversation between him and the curator for this work, I learned that the work became a product he related to his own body, as he used moulds of his hands and feet as objects inside the cocoons as they dangled from the exhibition space’s ceiling. I found a connection with my research around vessels as part of our story, referring to Le Guin’s work on the Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. (my Critical Review covers these ideas). By using these objects, I would say he celebrates the maker’s presence and probably also looks at human relationships and how we hold onto things. I like to link this to African basket weavers – we have a long tradition of basket making and cultural uses for different baskets. Considering symbolism within Zulu culture, there is a belief a basket should be made with love as it is supposed to carry “the energy” from when it was created until it finds its home with its owner.

The size and shape of these forms (of which there were 12) and how this artist interacts with his materials were inspiring to consider in my practice. I see a place where humans can hide in these sculptural forms. Still, these vessels could also become suffocating – almost indicating a claustrophobic, confined space if I look at the body parts dangling or seeking to view/show to the outside. It asks me to consider what I protect or hide from others and or myself.

I could relate to these works as my nest with raffia and ivy materials grew. This also inspired me to make the nest at least my length.

Looking at the form, which shares the shape of a cocoon, chrysalis, or nest, it refers to a place where things are born. From a contextual point of view, I find this installation and artist fascinating to learn from. The video below provided good insight into the making and thinking behind Warm Inside, 2022.

Baldock has a deep-rooted affinity to nature as he hails from generations of hop-gatherers and gardeners who have had a physical, emotional and sustaining relationship with the land. Inspired by Baldock the work below, (fig. 6) was made.

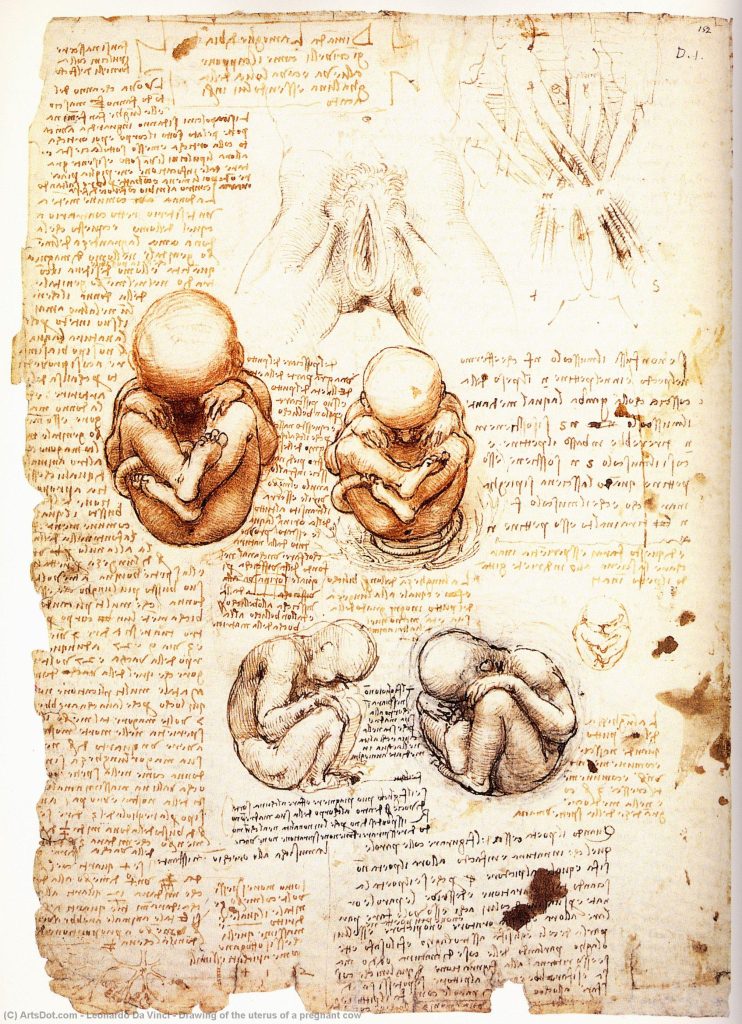

Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings

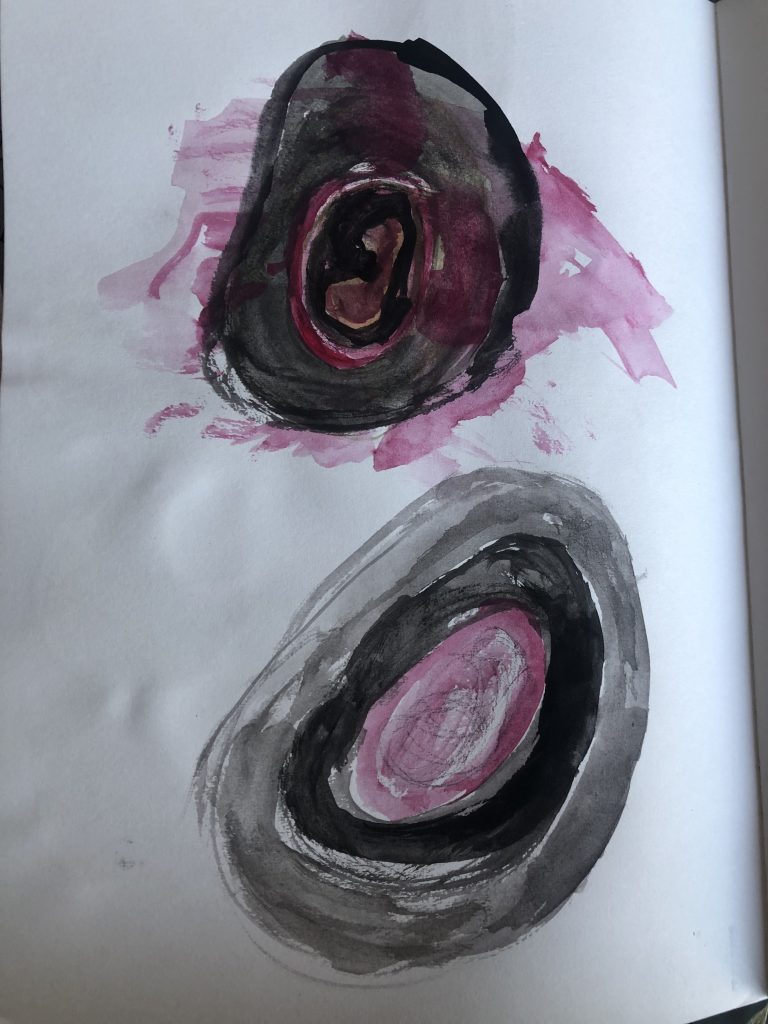

After looking at the work of Baldock, I was drawn to look at images of the womb and consider the nest as a womblike (pear-shaped) vessel and how I would start by doing explorative drawings. I needed to use red for blood and made three small sketches in sketchbooks with watercolour paint.

Leonardo expresses the human condition – his redition of the womb, it could also resemble an opened horsechestnut casing. Inside is the beginning of us all laid bare. Five hundred years ago, this artist and scientist shared some of the human mystery and wonder and holds up humanity as a fact of nature.

Magdalena Abakanowicz installation

In the work below, different forms of matter are connected and come to fruition with her textile Abakans, also called “woven paintings.” These three-dimensional works remind us of vessels that are huge, brightly coloured and textured. They could also invite viewers to step inside and cocoon within their structure. They cast eerie shadows across the walls as they take up space. The scale or size of these works are impressive and inspirational.

Kazuhito Takadoi works with natural grasses, twigs and twine

I came upon work by Kazuhito Takadoi, posted on a website op Jaggedart (https://www.jaggedart.com). This object was made with Hawthorn twigs and black waxed line twine. Kazuhito trained in Agriculture and Horticulture in Japan the US and in the UK, before studying Art and Garden Design in the UK. His works is about Nature and Time. It takes time for the grasses to grow, and then to be tender to embroider the works. As the grasses dry and mature, there is a subtle colour shift, which to him is comparative to seasonal change. I love the forms and the shadow play, which should happen when these works are hung as sculptures. When I read the following on his website, I felt connected with the work as their is, together with a sense of natures time also care involved in this making process as well as a connectedness with the natural materials: “…..Once harvested, the hawthorn twigs are de-thorned, cleansed and left to dry for a year before he can use them in his works. Then patiently, he ties them up with linen twine, white or black, sometimes even stripping the bark off the twigs.” The video below shares more about this process of care and the time to make.

I also looked at basket weavers in Australia and these works below captured my attention as both these artists are from indigenous backgrounds.

Anne-Marie Te Whiu (Te Rarawa) is a poet, weaver, cultural producer and editor. This installation was titled “ātete”. The mahi consisted of 51 baskets woven to represent the total number of innocent lives lost at the hands of a hateful (Australian) racist in Christchurch, Aotearoa on 15 March 2019. She created this piece with the intention of each woven stitch connecting us to those passed, as symbols of remembrance. It was woven with the wairua of quiet resistance, love, reflection, strength, unity and peace.

Fiona Campbell

This artist works in mixed media assemblages and focuses on rhizomatic connections as metaphors for life, vitalism and regeneration. Her work can be seen as activism around human exploitation of nature and over-consumption. She works with reclaimed, found and discarded materials to relate to waste. She regards materials as non-hierarchical and works labour-intensively, engaging directly with materials. Her work processes include weaving, wrapping, hand stitching, soldering, welding and casting. There is a play of contrasts and can suggest organic bodily forms, sometimes abject. I enjoy that through her work, she invites introspection and conversation and that, Alongside her practice, she works within the community on socially engaged projects. (This is what I would like to aspire to in sustaining my practice.

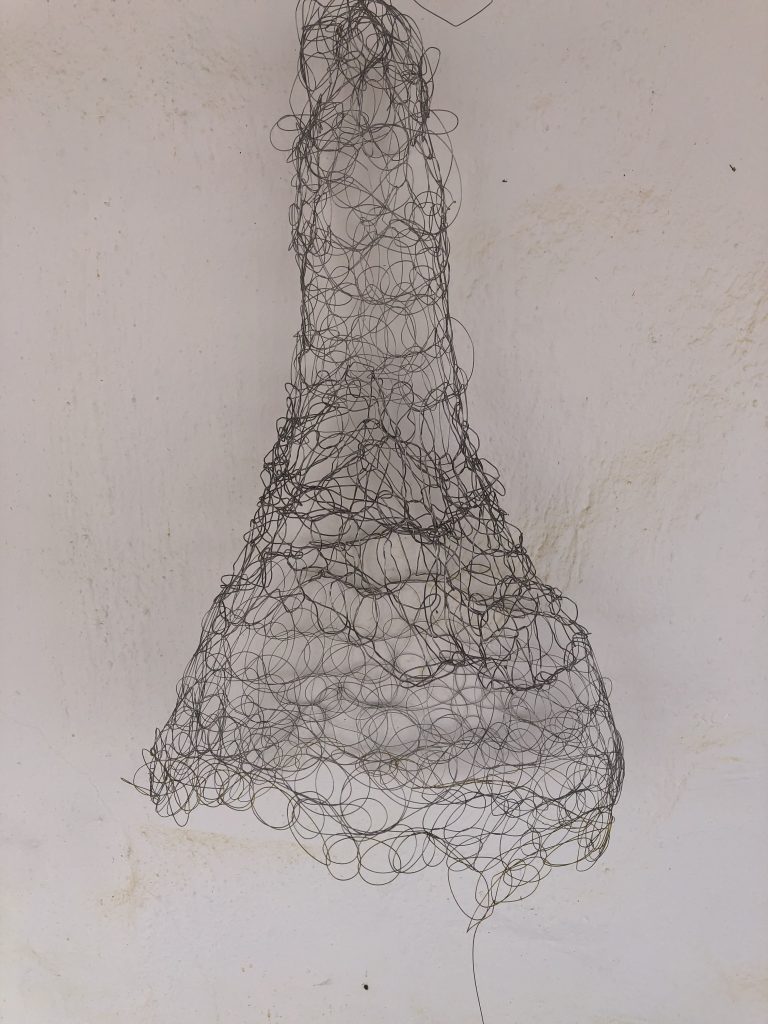

Her works strongly influenced the objects I make with wire by considering the use of the ‘floppiness’ within the form. I want to explore found materials. I regularly collect materials as I walk on the farm and would like to use them in my making. Below are works I explored with different materials. The latest work is the wire work in Fig. 13.

Reflecting and Reacting on explorative making continuing from the above research on artists makings.

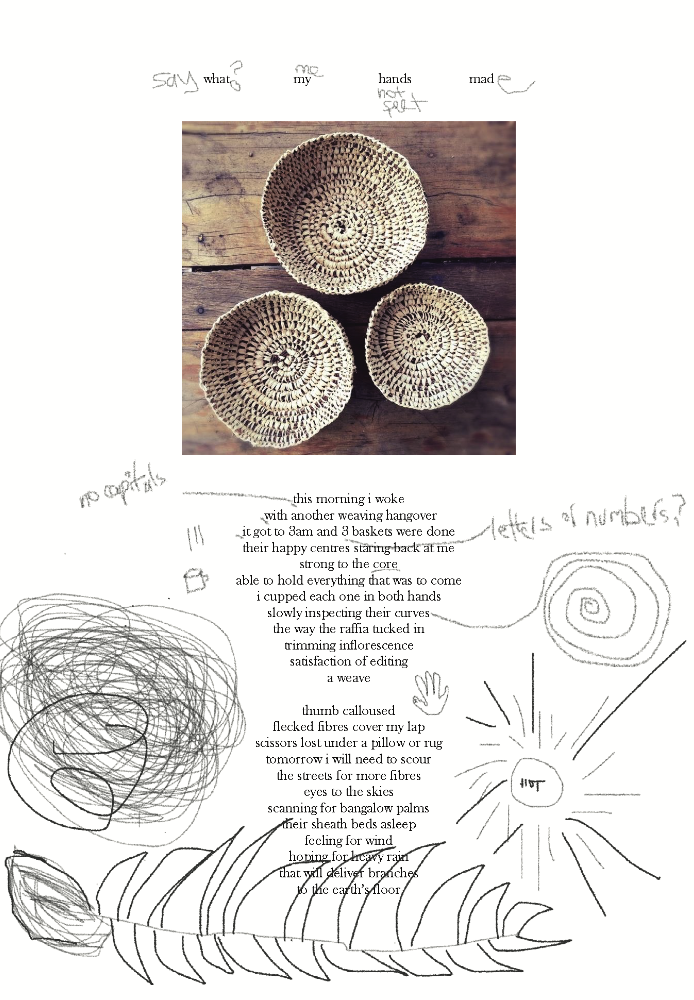

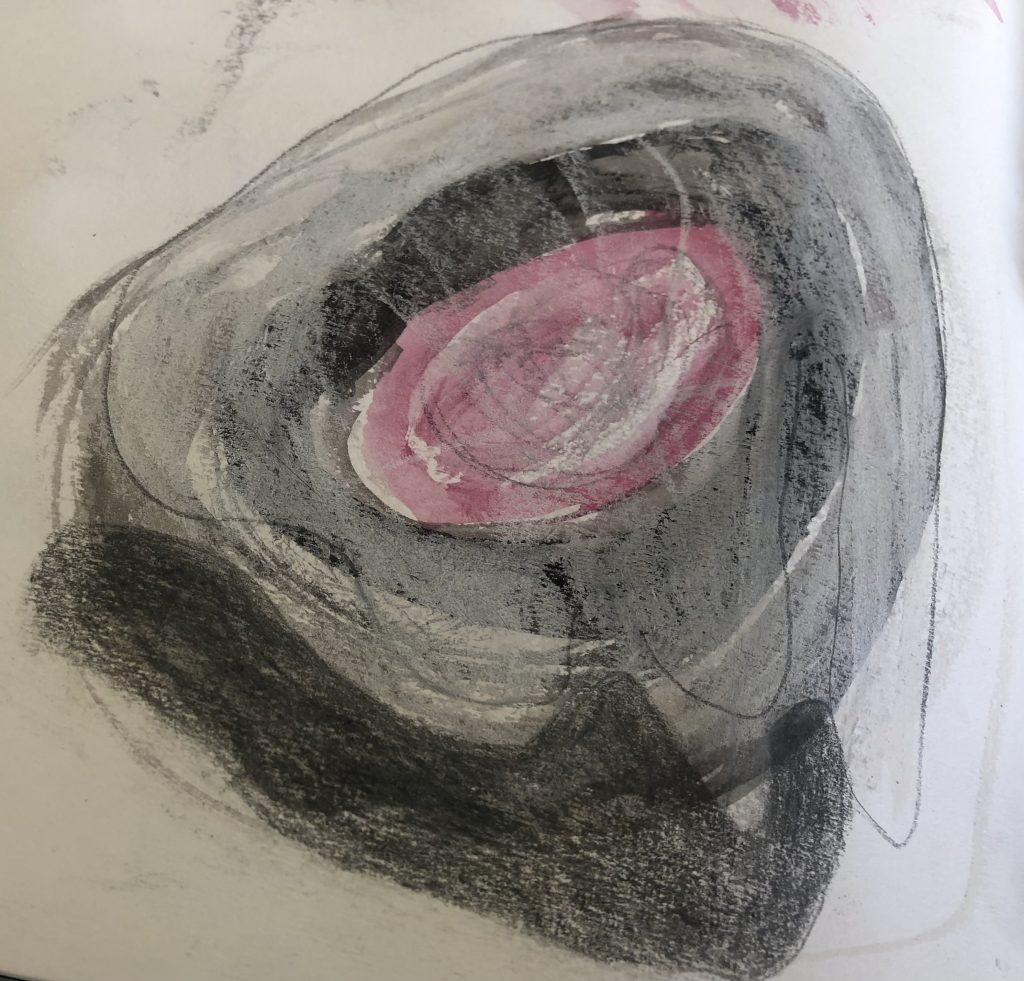

I share sketchbook drawings of a womb with watercolour paint. I am thinking about nests as structures that protect our vulnerability, which exists in nature, but also something we, as humans, can create and connect with symbols around protection and nurturing.

I went back to the drawings and added chalk and charcoal. If my work is about ‘interiority’, it is ‘egocentric’, or is this just a mental space I go to, like a haven? I came to the conclusion that we all come from here; I just needed to visit this nurturing space for my bodily connection in dealing with life.

I started playing with words: container, nest, womb and how did this happen? In the previous part of the course, part Four, I was asked in Project 2: “Where have you been and how did you get here?” The idea was to reflect on the route or planned path for the course.

Can I ask myself how things moved from objects to things?

Did I move beyond the image and can I look to my body of work as assemblies?

To bring this closer to theory and philosophy, I can state that I came upon ideas of Bruno Latour as to ‘How to make things public’ when he writes about Reapolitick to Dingpolitik. I hang onto the ideas that the things I made or explored are not only matters of fact, they have become matters of concerns, because of their complicated entanglements.

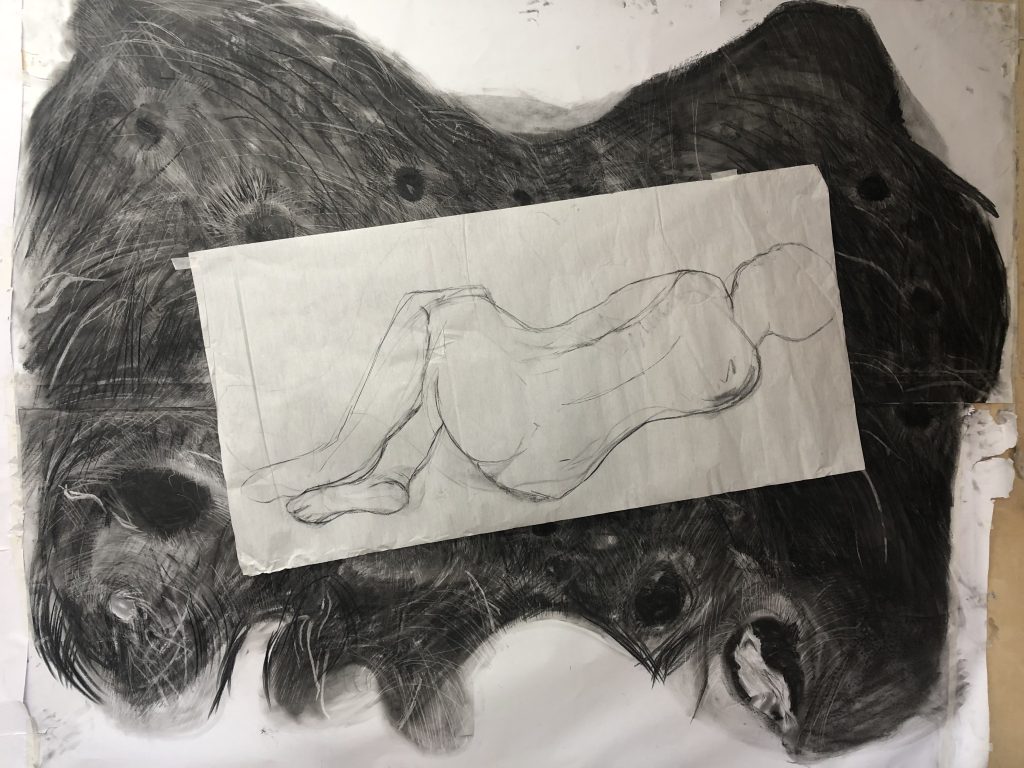

Playing with a life size cut out of myself into the nest drawing led to more figurative drawings, with the idea of the nest as a womb which nutures, shelters and protect. Could this be viewed as a comfort space? I like to think of the interconnectedness as we all came from a womb?

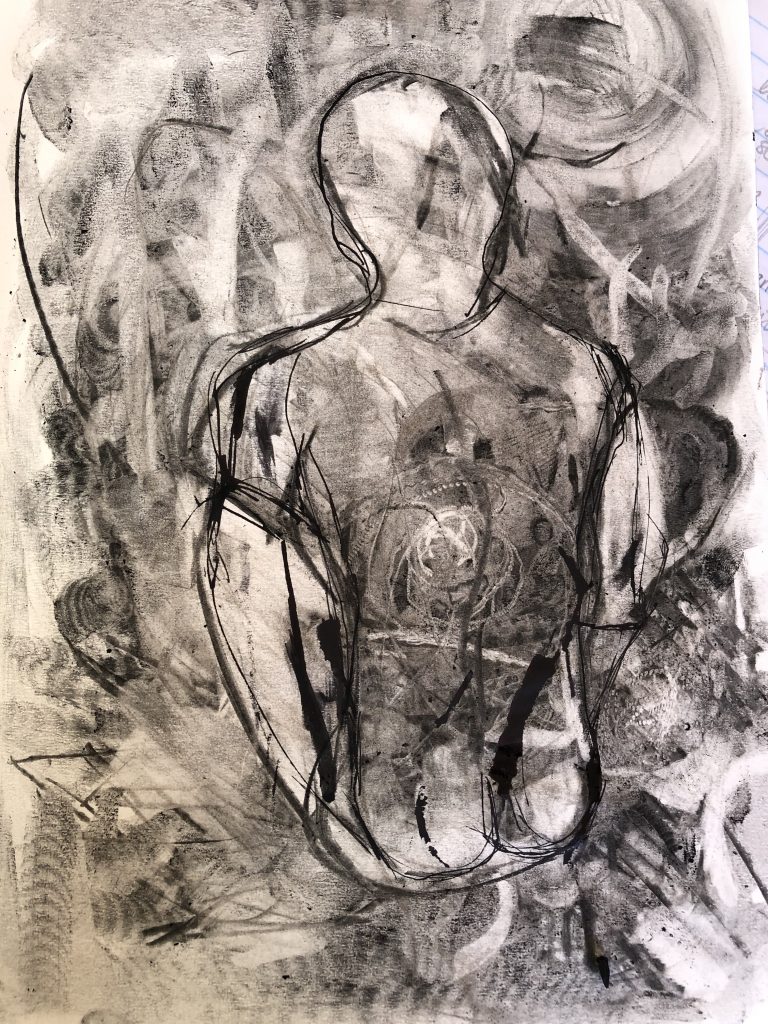

Exploring more figurative drawings as expressions of a human lying in a nest followed from here. These explorations led me to consider if I would draw with my body a nest and I looked at artists who use the entire body as an instrument to draw with and to view instructions around the drawing actions. I like the idea of showing the artist as present and using actions such as mark-making to show a process of making, in this case a nest. I need to understand if my plan can be called a ‘performance drawing’.(Fig. 16 Comfort Space)

- Can I show how a drawing turns into a performance?

- Do I have to have viewers present to call it a performative process?

- Does drawing become a performative process, whether a viewer is present?

- I like the idea of tracing out a nest by drawing through movement and a set of rules or reacting to bird sounds – even working outside between the birds.

M Lorhum

I have admired the work of artist M Lorhum, who writes about her work as follows: I see what I do as an exploration of drawing as a result of performative processes, wherein I focus on the act of drawing and the role that the body plays in that action, rather than pursuing a pre-determined final image.” Her artist’s creative process is based on a form of dance that positions itself between intuition and reason. She works with tracing and focuses on both individual and collective experiences and what is controlled and what is accidental. She says, “The body, its movement, its trace, spontaneity, and chance are key factors within my work.” Her work can be viewed as a performance, drawing, video, and installation. These media have a fragile and changeable nature in common with the mechanics of her artistic procedures. Her creative process is an oscillation between pairs of opposite concepts, such as intuition-reason, personal-universal experience, figurative-abstract, presence-absence, and, most importantly, control-randomness, exploring the possibilities between these concepts. Time, body and space are also essential ideas in her practice, where the movement of her own body in a specific place or action decisively determines the final appearance of the work. (https://www.degreeart.com/artists/m-lohrum)

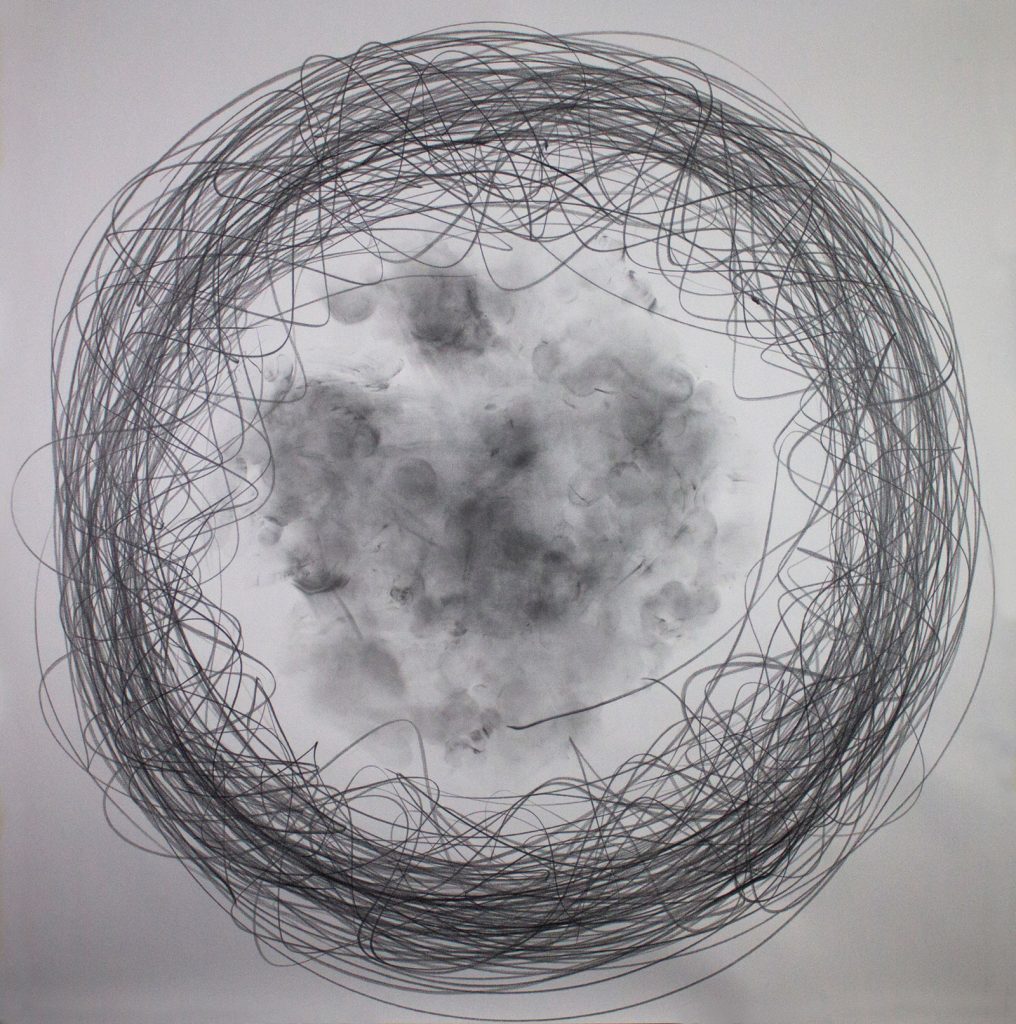

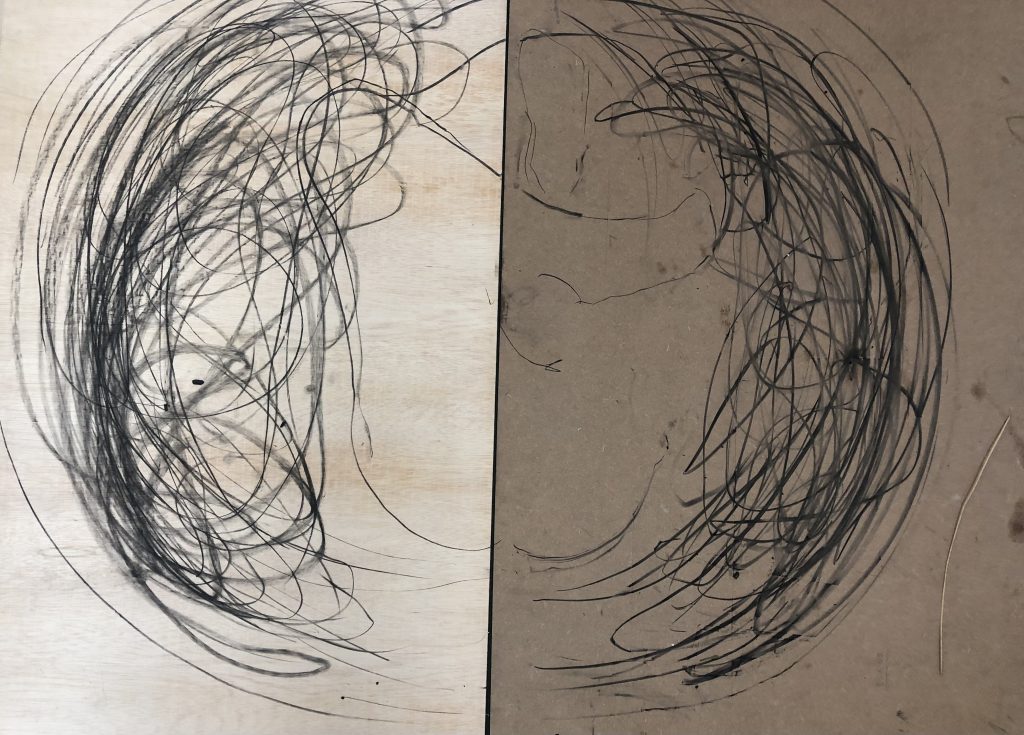

I viewed her work Circle as made with graphite powder and bars on Fabriano’s academic paper as an example to consider my own making, as a nest represents a circle to me. She traced her presence and performance on paper. While standing in the middle, she created line marks using graphite sticks in her hands and overlapped footprints with graphite powder. She used a metronome to set the rhythm and duration of her performance. This work was started by using 1.5 x 1.5 m of paper, on which she performed repetitive movement routines.

I do like the idea of using drawing as a focus on process. While one is busy making it, it is considered making under construction – a form is being built before it becomes visible. I will not know the outcome until the performance is finished.

The performative drawing video below was also researched to understand her work-making process.

In this series, M. Lohrum reflects upon how the dichotomies of presence/absence and trace/tracker operate in performative drawing. The artist starts using a square format of 1.5m x 1.5 m, where her body comfortably fits in. She then performs repetitive and systematic movement routines, using both hands or feet to trace her movements directly onto the paper with graphite or charcoal. This methodology generates beautiful abstract patterns derived from the symmetry of her body and movements. The resulting images encourage the viewer to track her traces and imagine her body performing on the paper by ‘reading’ the drawing.

I visited some Google sites on ‘drawing to perform’ and came upon an online mentorship program for Drawing Performance practice, mentored by Ram Samocha, but had to decline due to the cost.

I attempted to do a performative drawing on the floor of my studio at home. I used the board as the canvas – it made moving in a seated position more accessible, but I did find the space limited. I timed the work at 5 -7 minutes and took two photographs of the wip. I should have made a video, it would be my learning from showing more of the process of making this work. I had technical issues with my tri-pod and did not want to waste time, but this talks about the importance of preparation for future work.

Nestmaking with different materials was explored and is shared here as a collage work.

Ruth Asawa

Considering the practice of Ruth Asawa using a looping technique and developing some of her ideas on making biomorphic forms. Under Josef Albers, her training at the Black Mountain College was rooted in experimentation and influenced by modernist tradition. Her sculptures become a biomorphic form made of wire, suggesting seed pods or embryos within other forms. They carry ideas of a weightless and delicate appearance, which contrasts with the durable nature of wire.

Asawa learned the technique on a trip to Mexico in 1947 while volunteering as an art teacher for the American Friends Service Committee. She was interested in the wire-knitted egg baskets she saw on this trip. Local craftswomen showed her how they made the baskets, which influenced her to create her most recognizable sculptures by weaving wire. Ruth Asawa used different kinds of metals for her wire sculptures. She crafted the works by only using her hands to weave the metal into loops.

Looking at her looping techniques, one could also call it knotless netting.

On her method, I read the following on a blog site by Elaine Luther. She quoted from the book The Sculpture of Ruth Asawa: Contours in the Air: “All my wire sculptures are made from the same loop. And there’s only one way to do it. The idea is to do it, and you end up with a shape. That shape comes out working with the wire. You don’t think ahead of time, “this is what I want”. You work on it as you go along. You make the line, a two-dimensional line, then you go into space, and you have a three-dimensional piece. It’s like a drawing in space.” (Luther, 2019)

(added 09/02/2024): The role of Joseph Albers as a teacher in Ruth Asawa’s life. I think it is important to add her study at Blackmountain College under Joseph Albers. Albers fled Germany after the Nazis closed the famous Bauhaus art school and established the arts curriculum at Black Mountain in 1933. This college came to be identified with experimental art in America largely because of his pedagogical efforts and the calibre of visiting teachers he was able to recruit. His method of teaching was a structured exploration of discovery and invention. Albers’ influence on Asawa’s approach to work was profound. To the end of her life, she often described her work simply as “an experiment.” I would say that the emphasis on exploring perception and materials played a huge role in how Ruth Asawa developed her ways of seeing the world around her and using materials in nontraditional ways.

Reflecting on research and my making process

Good knowledge has been gained by looking at the artists mentioned above during the last few months. A fellow student in our EU group shared an article by Johan Dunnigan, Thingking, with me. I think it appropriate to discuss the primary learning from this. According to this Rhodes Island school of design professor (dept head: Furniture Design) the word, ‘Thinking’ express a ‘symbiotic relationship between making and thinging in art and design, between object are idea. In this way, it becomes the connecting factor that relies on knowledge, practice, and research. I see it as a reflection of the effects of the creative act on the artist (maker), the user and the system. It is a space where, as creatives, we compare our thoughts during the making with what happened. He refers to mythology, which shares a fluid relationship between ways of knowing and how it is demonstrated. The embodied knowledge refers to skills used to transform raw materials into the expression of an aide. He suggests two vital elements in this model: critical thinking and critical making. In critical making, the process is where new possibilities open for thinking and inquiry, which could then stimulate discovery. These ideas suggest we use tools and materials and explore them in our practice while guided through design (technical/drawing/ painting/making. I like the idea of focusing more on making the finished product, where we gain knowledge. I think this article relates well with the article by Rebecca Fortnum, whom my tutor shared with me during a tutorial in September 2023 (Blog:https://karenstanderart.co.za/on-not-knowing-reading-rebecca-fortnum-as-recommended-by-tutor-m-whiting/).

In summary, the perspective encourages the artist to view the act of making as a thinking process, where one places emphasis on the integration of theory, reflection and intentional decision-making.

My main inspiration for making with wire came from Ruth Asawa’s techniques. I see her work as airy and buoyant sculptures, and I have learned that my works are best displayed when suspended from the ceiling. Regarding her skill, I should be realistic and work with the wonkiness in my making. I was inspired to work with this idea when I researched the work of Fiona Campbell. Her almost primal organic forms play with presence versus the near perfection in the work of Asawa. As if it is still in the process of becoming (growth), I feel I explore ideas of material truth where textures and transparency are evident.

List of Illustrations

Fig. 1 Severjins, Bianca. (2017) Nesting Vessel no 5. [Photograph] At: https://biancaseverijns.com/nesting-series-2/ (Accessed 02/11/2023).

Fig. 2 Stander, K. (2023) Nesting after a sociable weaver. [paper, wire and twig] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 3 Baldock, J. (2021) Warm inside. [Photograph] At: https://www.stephenfriedman.com/news/600-jonathan-baldock-warm-inside/ (Accessed 30/10/2023).

Fig. 4 Baldock, J. (2021) Warm inside. [Photograph] At: https://www.stephenfriedman.com/news/600-jonathan-baldock-warm-inside/ (Accessed 30/10/2023).

Fig. 5 Thula Tula Mill featuring My Africa cotton suede Zulu Basket. [Photograph] At: https://www.thulatula.com/cdn/shop/files/ARANDA_MY_AFRICA_COTTON_SUEDE_ZULU_BASKET_1400x.jpg?v=1683144419 (Accessed on 02/11/2023).

Fig. 6 Stander, K. (2023) First object/cocoonlike inspired by the work of Baldock. [Photograph of object woven with raffia ] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 7 Windsor Castle, Royal Collection. [Photograph] At: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2014/mar/21/the-10-greatest-works-art-ever (Accessed 02/11/2023).

Fig. 8 Abakanowicz, M. (1960’s) The Abakans. [Photograph] At:Tatehttps://www.tate.org.uk › whats-on › magdalena-abak… (Accessed 02/11/2023).

Fig. 9 Te Wiu A. (2023) “ātete”. [Photograph ] At: https://www.anne-marietewhiu.com/weaving (Accessed 13/11/2023).

Fig. 10 Te Wiu A. (2022) A bibliography of Weave. [Screenshot] At: https://unprojects.org.au/article/a-bibliography-of-a-weave-2022/ (Accessed 12/11/2023).

Fig. 11 Campbell, Fiona. (2013) Cocoon. [Photograph] At: https://fionacampbellart.co.uk/commissions/giant-nest/h0qi7024d5smgadylj3bz6acps4knm (Accessed 08/01/2024)

Fig. 12 Campbell, Fiona. (2017 ). Spiky Cocoon II. [Photograph] At: https://www.saatchiart.com/art/Sculpture-Spiky-Cocoon-II/61221/504204/view?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=2200&epik=dj0yJnU9MWU1eVNnd3h4Nk9Oc3N5MmhpQjJwVmpaSTFtR0FveW8mcD0wJm49dmN3YkNuTlo1b1R0OXUtdl9NT3hCQSZ0PUFBQUFBR1c1N0E4 (Accessed 07/01/20240.

Fig. 13 Stander, K. (2024) Looped object. [Photograph of work in progress] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 14 Stander, K. (2023) Object with raffia [Photograph] In possession: of the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 15 Stander, K. (2023) Object with twine [Photograph] In possession: of the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 16 – Fig 18 Three Sketchbook explorations. [Photographs] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 19 Stander, K. (2023) Womb nest. [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 20 Stander, K. (2023) Womb nest, a drawing exploration. [Photograph] In possession of the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 21 Stander, K. (2023)Womb nest with figures – an exploration. [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 22 Stander, K. (2023) A Comfort Space. [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 23 Lorhum, M. (2020) Circle. [Photograph] At: https://www.degreeart.com/artist-artwork/52981 (Accessed 04/12/2023).

Fig. 24 Loruhm, M. (What is performative drawing [Video] At: https://vimeo.com/471243470 (Accessed on 04/12/2023).

Fig. 25 Stander, K. (2023) WIP [Photograph of performance] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 26 Stander, K. (2023) Nest drawing [Photograph of finished performance work] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 27 Stander, K. (2024) Collage of nests [Photograph of four nests with paper, twine, dried grasses, raffia and coir] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 28 Asawa, Ruth. (1948-1949) Basket [Photograph published online and in possession of the Black Mountain College Collection] At: elainelutherart.com/ruth-asawa-and-the-mythical-basketmaker-of-mexico/ (Accessed 05/01/2024).

Bibliography

Baldock, J. (2021) [Video] In: https://youtu.be/r9bfwigBmKY (Accessed 31/10/2023.

Black Mountain College Museum & Arts Center. ‘Ruth Asawa’ At: https://www.blackmountaincollege.org/ruth-asawa/. (Accessed 05/01/2024).

Collias, Nicholas E., and Elsie C. Collias. 1962. “An Experimental Study of the Mechanisms of Nest Building in a Weaverbird.” The Auk, vol. 79, no. 4, 1962, pp. 568–95. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/4082640. Accessed 15 Nov. 2023.

Dunnigan, John. ( 2013) ‘Thinking‘ In: Somerson, R. and Hermano, Mara l.(eds) in The Art of Crital Making John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. pp 94 -116.

Frutnum R On Not Knowing. Pdf shared by tutor M Whiting

Luther, Elaine (2019 ) Ruth Asawa and the Mythical Basketmaker of Mexico At: https://www.elainelutherart.com/ruth-asawa-and-the-mythical-basketmaker-of-mexico/ (Accessed 04/01/2024).

Severjins, Bianca article in Allthings Paper, 2017. https://www.allthingspaper.net/2017/01/monochromatic-hand-torn-paper-art.html

Sharma, Manu. 2023. Engaging with M Lohrum on her performative drawing practice. Read online at: https://www.stirworld.com/see-features-engaging-with-m-lohrum-on-her-performative-drawing-practice