- A final body of work, with a written document/plan that articulates a draft selection for assessment, using the learning from your editing process.

- Reflective Commentary of between 500 and 750 words.

- Artists’ Statement – the final version of between 300 and 500 words

I decided to share this blog for Assessment (Feb 2024) as part of the Reflective Presentation. I shared the link to access this blog with the assessors, and I believe it gives an impression of my making and thinking while writing. I will share the BOW shown in this blog as a separate (post) folder under Selection of Creative Works in the G Drive

For the sake of the assessors, I place the link to this site: https://karenstanderart.co.za/assignment-five-assessment-preparation/

ASSESSMENT PREPARATION

Final Body of Work and written document/plan that articulates the selection for assessment

A few questions came up:

Do I name these works?

How do I place the work in its context, and how does it relate to the work of other people I researched?

Also, consider the importance of good images for the upcoming assessment.

SELF EVALUATION SUMMARY

How does the work measure up with the assessment criteria?

THE BODY OF WORK TO BE PRESENTED

Written document/plan for this selection

This document is intended to illustrate my aims in achieving the learning objectives by sharing the outcomes. I decided to focus mainly on one part of my body of work for this assessment, which is the ideas around nests and tenderness of care in terms of making and symbolic meaning. In this presentation, I share materials I explored, new skills I learnt, and how this was informed by my contextual study around interconnectedness between human and non-human.

Fig. 1: A Space where All Can Meet, 2023 – This work is made with raffia and takes the form of a nest, a place of safety within nature. It contemplates the time it takes to make or create and place but also carries the idea of care, hands holding it.

Fig. 2: After The Envelope: exploring a social weaver’s nest, 2023. I began researching Claire Falkenstein’s wire sculptures, which she called ‘drawings in space’. They evoke ideas of interconnected infinity, which I learned as I worked more with wire later in the course. The forms became an inspiration to consider the scale between humans and birds.

Fig. 3: Meetingplace , 2023. These nests have been placed outside since 23 October 2023 to document how they interact with the landscape. I could incorporate music on Instagram into a moody image taken from these objects during a full moon evening. I felt these works brought discussions around the sounds of birds on the dam close by and even suggestions that birds might nest here. Materials used were raffia, ivy shoots, wire and gypsum.

Fig. 4 :Paper Nest 2023. I got more inspiration from artists I researched regarding the use of paper as material to make with. This work talks about fragility and time but carries the idea of nesting with twiglike materials, which the weaver birds in the Kalahari use to make the vast nests.

Fig. 5: Weaver Nest 2023. I placed this nest next to our home as a reminder of human and nonhuman needs for shelter and vulnerability. I live in one of the older farmhouses in our area. It dates back to around 1780, shortly after this village became a farming community for European settlers. It also tells a story of place and the history of settlement and colonialism. The work is inspired by my research into Claire Falkenstein’s work and material explorations during the course.

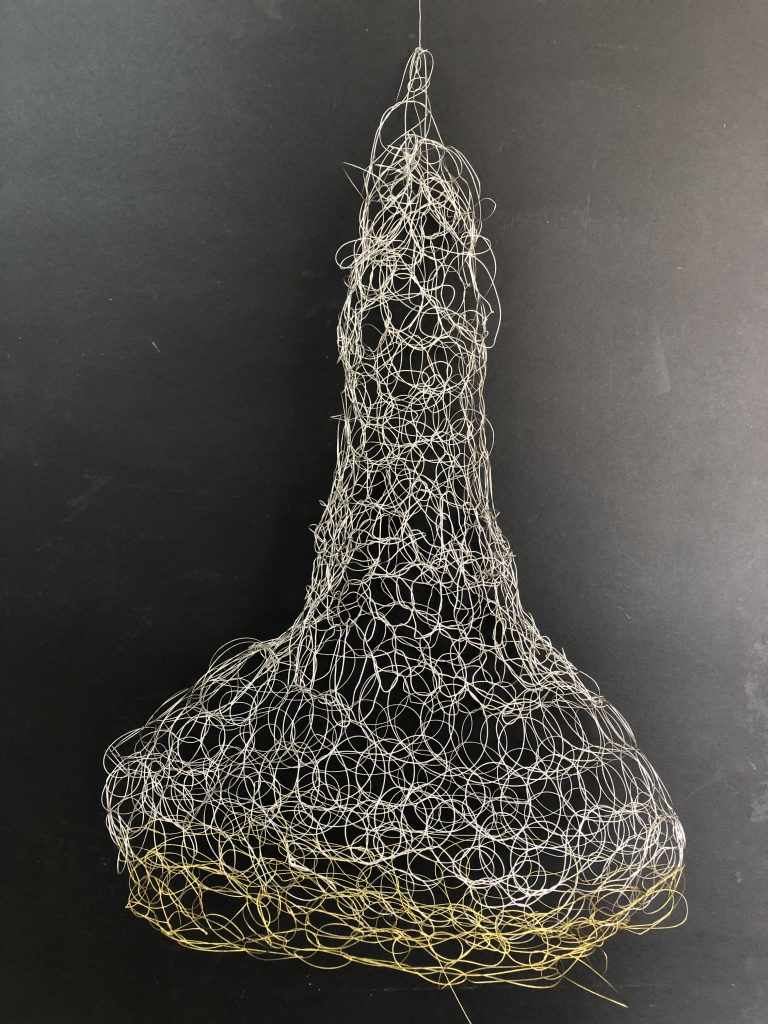

Fig. 6 : Wired 2023. A nest made with Tiger Tail, 0.38mm thickness. It has silver and gold threads and is inspired by the work of Ruth Asawa. It shares research into making 3d objects as installations and exploration of new materials.

Fig. 7: Ephemeral explorations 2023. Drawings with feathers and mushroom ink.

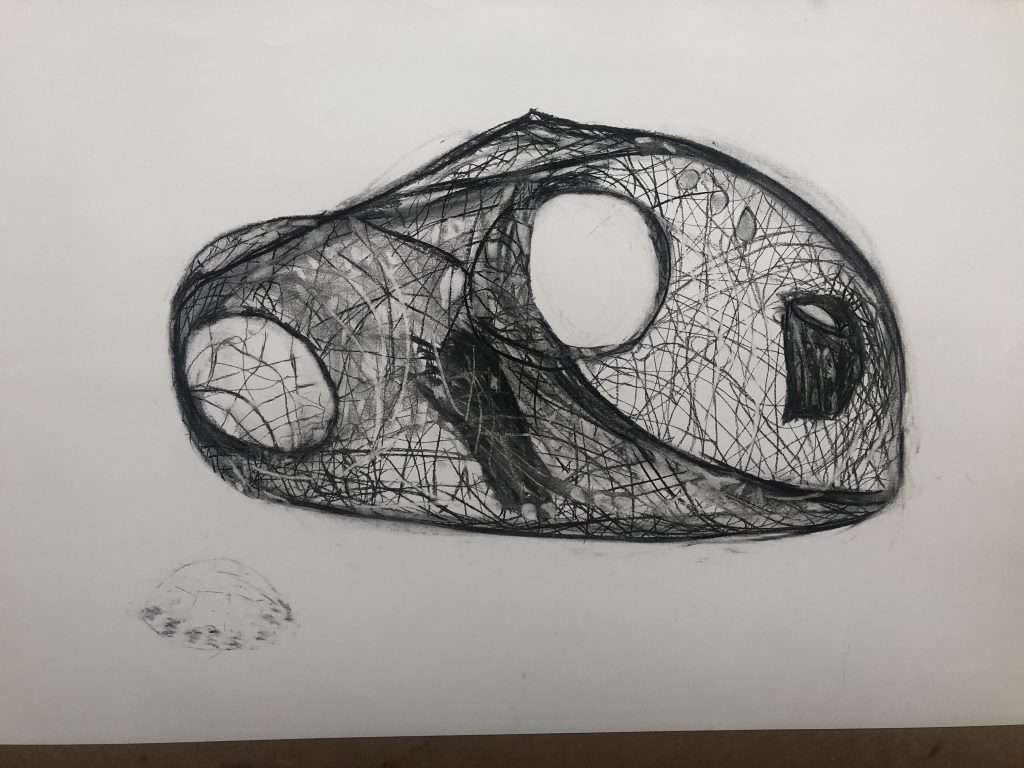

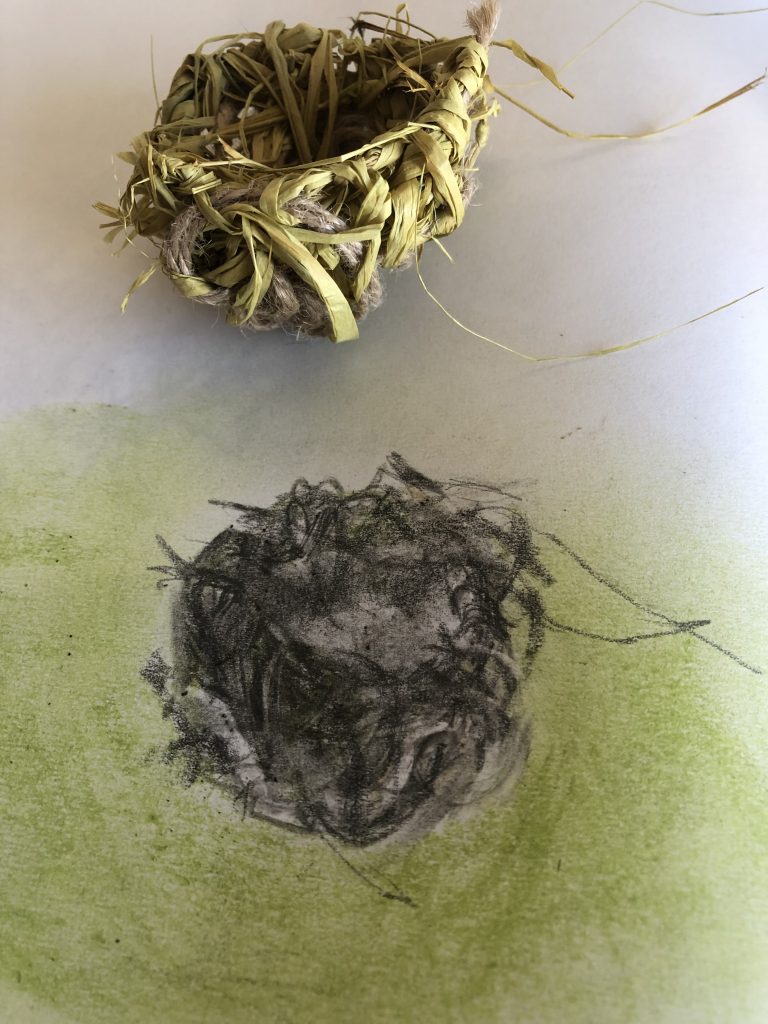

Fig. 8: Drawing a nest 2023. Exploring small-sized nests and material possibilities.

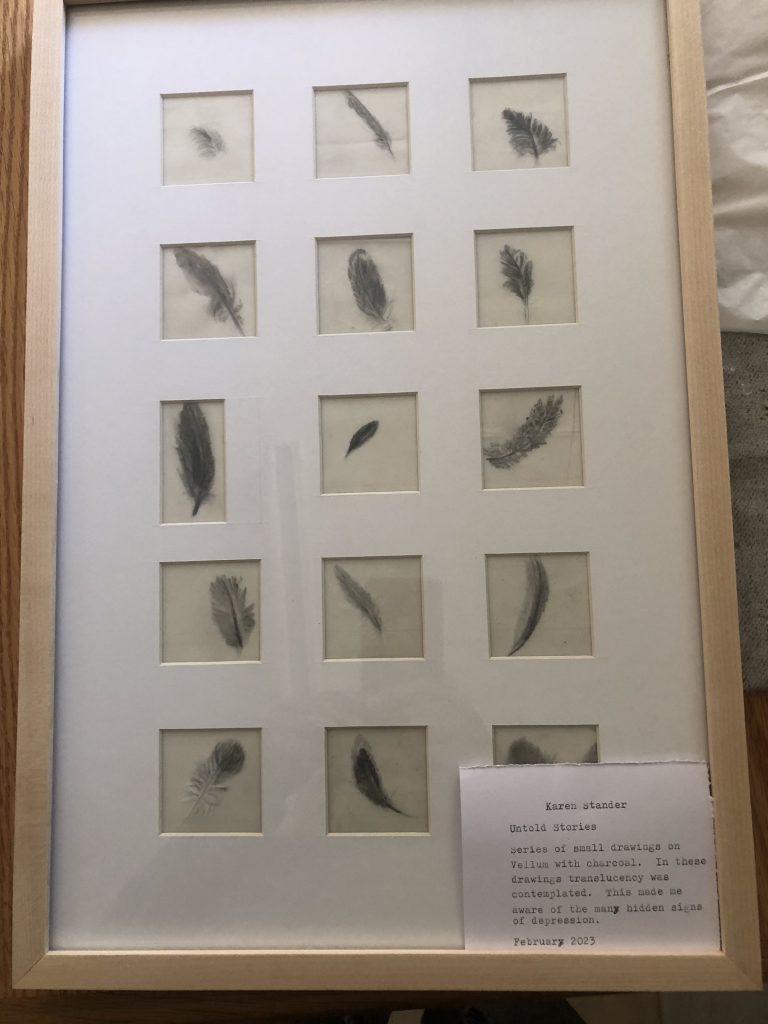

FIg. 9: Collage of feathers, 2023. These drawings on translucent paper are framed and share an insight into my daily drawings and the use of repetitive themes in this practice.

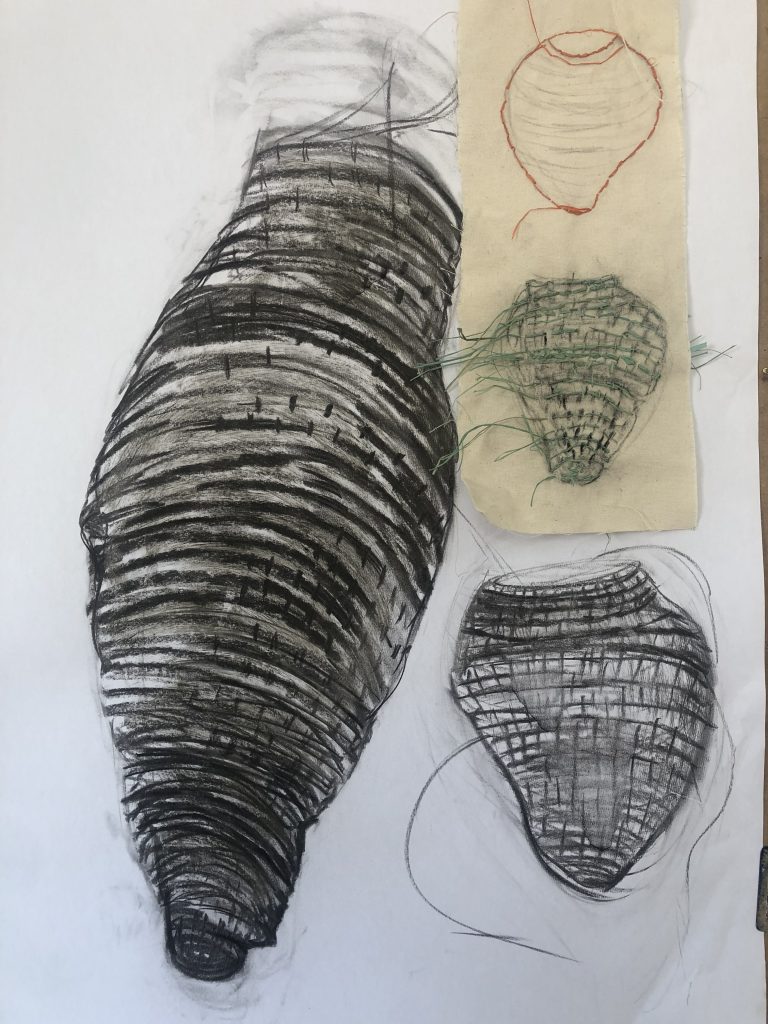

Fig. 10: Nest, 2023. This is a Charcoal drawing of a life-sized nest, focussing on the scale of these non-human-made nests I found in nature to photograph and study.

Fig. 11: Weaving objects, 2023. Works made with raffia, which flowed out of nest making – the also resemble cocoons or seed pods.

Fig. 12: Drawing made objects, 2023. I Consider how weaving leads to drawing and vice versa. It is about taking a line for a walk. Abstract forms remind me of nests, and I felt this drawing of an abstract form became a nestlike container for ideas about symbiotic influences in my practice.

Fig. 13: A Collage of Made Nests, 2023. By presenting the made nests as a collage, consider vulnerability, materiality, and life.

After discussing it with my tutor and looking on the OCA website, I found the following information valuable for writing a reflective commentary.

“Reflective Commentaries: A Reflective Commentary is either a short piece of reflective writing (500 words for Levels 1, 2 and 3; or 350 words at Foundation Level) considering the particular assignment it accompanies, or it’s a longer piece of reflective writing which you submit at the end of the unit in which you reflect on your learning over the unit as a whole, concerning particular assignments (especially the final assignment).” (https://www.oca.ac.uk/weareoca/creative-writing/writing-a-good-reflective-commentary/ I understand this is not the place to write how I came up with an idea or works I discarded. I should focus on the work I submit, the intention, why I share it and how it sits with other artists’ work and measures up with the assessment criteria.

I decided to re-write the below(first) reflective commentary as a self-evaluation summary and re-visit a different way to write a thoughtful commentary or essay. It should focus on my critical engagement with other artists and the research and place my work within this context. I returned to earlier course material, Exercise 1.3: Writing a Reflective Commentary, and took some notes. (Fine Art 3 Advanced Practice, 2020:18-21)

This is the first draft (778-word count), which I, after tutorial discussions, consider more as a self-evaluation summary.

I was influenced by finding connections between my materials and the natural world during my making. I was inspired by the Research part of the course, where I looked at how connectedness with the non-human world inspired contemporary art. I developed work and was encouraged to experiment and explore alongside the course material. This opened me up to the flow of making, accepting mishaps and accidents and focusing on the process. The materials I worked with were primarily natural fibres, and I saw my preference to work with charcoal and natural pigments as I developed drawings. As my studio became a container for these ideas, I wanted to move outside into nature. Working with fungi almost naturally directed me to feathers, bird nests, and weaving with natural fibres.

I am more aware of the importance of drawing in my practice as I continue to think about tending and care and how this interacts with routines in my studio or as rituals to deal with things around me. I became interested in nests as another way of working or making with the non-human. There was an almost natural progression when I explored nests of birds. Looking and drawing nests became a metaphor for care and led to exploring making nests with natural fibres. I studied materials I have never worked with, and now I look at this weaving process as a form of drawing and creating shape and texture.

I became interested in the work of fibre and land artists who connect with nature and natural materials. I looked at the sociable weaver’s nest, only found in parts of Southern Africa. These Sociable weaver nests are the largest structures built by birds. I learned how this species survives mainly in desert areas and forms strong cohesion with the remaining birds in these vast nests. The young birds live in the same nest chamber with their parents through their first winter, travel to feeding grounds daily with their family’s colony and even enjoy free meals from their parents for months after learning to fly. In my research, I realised that birds twist, wind, and manipulate materials, but weaverbirds intentionally tie knots and weave grasses.

As discussed in his book “The Perception of the Environment,” Tim Ingold’s perspective on dwelling challenges traditional views that attribute behaviours solely to genetic factors. Instead, Ingold emphasizes the importance of the environment and ongoing engagement with it in shaping human existence. (Ingold, 2000:185-187). He compared it with how indigenous people of New Guinea make string bags, or bilums. (Ingold, 2000:358-260)with the abilities of the weaverbird to make nests, and concluded that like those of the human makers, their abilities are developed through active exploration of the possibilities within the environment, such as the choice of materials and structural supports and bodily capacities of movement, posture, and prehension. He writes that the key to a successful nest builder is the ability to adjust movements (when making) with exquisite precision concerning the evolving form of its construction. This is developing a skill and learning from experience. In an earlier chapter Ingold talks about worlds being made before they are lived in (Ingold, 2000:194). He also refers to ideas about ‘to build and ‘to dwell’. The act of dwelling precedes and informs the act of building and to Ingold, the act of thinking is inseparable from the context in which it occurs.

My making process was slow. I started with drawings, then developed bigger nests until I made one that compared to my human size. These nests are sculptural and remind me of the works made by artist Claire Falkenstein. By considering her work and looking at the nests as objects, I focussed more on the materials I used. In developing this, I can connect the materials with stories of making in indigenous cultures or non-human making. I want to create installations or performances that play with scale.

While making these nests, I looked at fibre artists who make fibre installations and 3D objects and apply many weaving skills. The first objects I made were created using a spiral pattern, where I started coiling raffia and using a blanket stitch to make the threads that hold and form the works. I am left-handed and work in a clockwise direction. I have the fibre’s core in my right hand and stitch with my left hand. During this process, I was always aware of my materials and that my technical skills needed to develop. I regularly interacted with fellow students in the Textiles course, who could give feedback and critique the work.

I am asking a new question: What if I consider my studio a space to connect with the outside world?

I consider my studio outside the farmyard area as an exhibition space with interactive elements. I could invite viewers to participate in an ongoing art piece, like working on a current container/nest. I will photograph most of my body of work for this assessment outside.

REFLECTIVE COMMENTARY (final version)

Critical moments in how my practice developed are the influence of a wide range of artists I researched, explorations with different materials and my research practice, which focussed on interconnectedness in art making. I was encouraged to continue asking the why question: why am I making my decisions,

where have they come from, and why do they add to my work? I was also encouraged to continue to deepen my reflection and consider more comprehensive sources of contextual information outside the arts to inform your making.

Asking questions about connectedness with non-humans led me to research New Materialist ideas and be strongly influenced by materiality, which draws on a broad historical and geographical perspective and always pulls me back to the connectivity standpoint between humans and non-humans.

Working primarily with natural materials and fibres, I wanted to collaborate with my materials or objects and write about this experience. Within this exploration, experiments with mushroom inks and feathers led to using blotting and marks, which developed out of spore printing and then to explore feathers

and nests and consider care alongside my drawing and making practice. I became influenced by looking at ways to bring nature into my practice and my work into nature. The work of land artists and fibre artists strongly influenced the direction of my work, and a shift in making occurred when I became more interested in weaving and working with fibre.

In making nests with fibre, I learned I could manipulate materials to create 3D forms and explore the weaving of natural forms, which responded to nests made by birds in nature. The form was inspired by learning and observing the skills of current fibre artists and fellow OCA students and researching the organic forms made by female artists like Claire Falkenstein and later Ruth Asawa and Fiona Campbell. These forms could also be easily reinterpreted as drawings, which I share as ideas developed from research and making. As I explored wire as a material and the idea of working inside out, I made vessels with raffia and soft wire and felt inspired by learning weaving techniques. I look at gradually learning and exploring different materials in this process. I learned about considering little/smaller works and experiments and reflecting on kinships I have found in the making for the last few months. Exploring scale and working with works I could place outside in nature helped me find connections. I became aware of my vulnerability and that the nests could become a container or protective space if I explored upscaling them to human size. This also alludes to a studio being a space to connect with the outside world and a container of thoughts. I was again reminded of my interest in the process and ideas of P Barlow about the artistic journey, namely that work takes the artist on a journey and not the artist taking the work/materials on a journey.

My strengths in the works I present are how these works can all be placed back into the landscape and find kinship with nature. I love thinking of them as work in space and how shadows and light can come into play. This making opened up ideas to explore and play with a scale between human and non-human

worlds and explore the provisional nature of my making and how I could look to future work. I learned new technical skills to make 3d works, which informed my practice around interconnectedness with nature.

ARTIST STATEMENT

Karen Stander resides on a farm in the Riebeek Valley in the Western Cape, South Africa. Here, she explores the connectedness between human and non-human by working with natural materials to make objects, drawings and paintings, which asks questions about how we give voice to the non-human world by looking at the natural world through mushrooms, feathers and nests in her recent body of work. The artist is drawn to how care and relating (kingship) are part of making and thinking in the creative process of the contemporary artist practice. Her work reminds us of a vital microcosm of human and non-human agents as she explores her work, which she calls ‘para-sites’ as different explorations of interconnectedness.

For creating her body of work, the artist looked at theories of new materialism and eco-feminism, which critiques the dominant Western outlook on humanity, which has placed humans as independent of nature to justify the domination of a patriarchal system. She states that she was encouraged by Dona Haraway, a leading thinker on kindships and multispecies communities, to visualise her body as a flow of organic and synthetic materials home to millions of microbes, bacteria and fungi.

In her body of work, the artist shares found objects collected from walks in nature by foraging, collecting and translating them into daily drawings, documenting time-based work processes of knotting and weaving materials into nests and cocoon-like objects. The artist enjoys working primarily with drawings and prints, making objects, and keeping a reflective writing practice. The artist wants her viewers to consider the natural process of decay and decomposition, strength and fragility, and nurture and care, as she plays with boundaries between the experience of making with nature and a viewer’s reality, which is mainly disconnected from the natural world.

My artistic evolution encompasses a dialogue between materials, nature, and human creativity. The weaving of nests serves as a metaphor for care and vulnerability as well as a testament to the intentional and skilful acts of humans and non-human entities in creating meaningful, interconnected spaces within the world we collectively inhabit. I want to think that my practical work became a weaving together of different ideas I explored in the research part of this course. This became a rather messy space and I had difficulties always being transparent about my process. By the end of this course, I realised my main concern was giving a voice to the non-human world through my making and that making became a process of becoming and growth. Organic forms in my 3d works play with presence and transparency.

SELF EVALUATION SUMMARY

In my artistic journey, the profound connection between the materials I work with and the natural world has been a guiding influence. This exploration gained momentum during the Research phase of my course, where I delved into how contemporary art draws inspiration from interconnectedness with the non-human world. The encouragement to experiment and explore alongside the course material fostered a fluidity in my creative process, fostering an acceptance of mishaps and accidents and a heightened focus on the evolving journey of making.

Natural fibres became my primary materials, and my affinity for working with charcoal and natural pigments unfolded as I delved into the drawing. The studio transformed into a vessel for these evolving ideas, prompting a desire to extend my artistic exploration beyond its confines and into the embrace of nature. The organic progression from working with fungi seamlessly led me to feathers, bird nests, and the intricate art of weaving with natural fibres. I look at the progression and development of work as part of being in a space of becoming or being in-between with the non-human and finding or searching for connections. I have often wondered about my emotional energy and how making became a way to deal with it – could I say that physical making embodies some of that energy?

Intrigued by the works of fibre and land artists who deeply connect with nature and natural materials, I turned my attention to the Sociable Weaver’s Nest, a marvel found in parts of Southern Africa. These intricate nests, the largest built by birds, became a source of inspiration. Studying weaverbirds’ intentional tying of knots and weaving of grasses shed light on the deliberate and skilful aspects of their nest-building activities.

As I continued to reflect on my practice, drawing emerged as a central element, intertwined with themes of tending and care. This contemplation extended to the rituals and routines within my studio, becoming a poignant exploration of how these practices interact with the world around me. Nests captured my interest as a unique avenue for non-human collaboration. What began as an exploration of observing and drawing nests metamorphosed into a metaphor for care, inspiring me to experiment with creating nest-like forms using natural fibres.

The process led me to study materials previously unfamiliar to me. Now, I perceive the act of weaving as a form of drawing, a method of creating shape and texture that transcends the conventional boundaries of artistic expression. A practical example is my recent work exploring soft wire and raffia. I later removed the raffia to find the vessel would become floppy but still intact – learning it would work much better as a hanging object. In a discussion with my tutor about this development in my work, we discussed the intellectual space, which refers to the conceptual aspects and boundaries between techniques, and the ideological space, which relates to your artwork’s underlying beliefs or themes. The integration of drawing and weaving should become (seen as) a means to dissolve these boundaries and bring forth the deeper intentions of artistic expression. During the last weeks of this course, I started exploring a looping technique inspired by my research into the work of Ruth Asawa. This work is still a learning process, but much has been learnt about weaving as a drawing and weaving with an endless piece of string. I hope to explore this as my course continues.

As presented in “The Perception of the Environment” (Ingold: 2000), Ingold’s perspective on dwelling significantly influenced my understanding of the dynamic relationship between humans and their surroundings. He challenges the notion of behaviours being solely attributed to genetic factors, emphasizing the pivotal role of the environment in shaping human existence. Drawing parallels between the abilities of the weaverbird to make nests and the skills of indigenous people crafting string bags, Ingold contends that these abilities evolve through active exploration within the environment, considering factors like material choice and bodily capacities.

My making process unfolded gradually, starting with drawings and progressing to larger nests, culminating in one that mirrors the human scale. These sculptural nests evoke the works of artist Claire Falkenstein and prompt a focus on the materials used. Inspired by Falkenstein’s approach, I aim to connect these materials with the narratives of making in various indigenous cultures and the non-human world. My desire is to create installations or performances that play with scale, exploring the intersection of human and non-human creativity.

The act of dwelling, as expounded by Heidegger, became a key theme in my exploration. “We do not dwell because we have built, but we build and have built because we dwell.” This philosophy underscores the intrinsic connection between dwelling and building, with dwelling being a prerequisite for meaningful construction. It resonates with my experience, where the act of thinking and making is inseparable from the context of my existence.

My journey also led me to consider the studio as more than a physical space—it is a gateway to connect with the outside world. This contemplation has sparked ideas of transforming my studio into an outdoor exhibition space with interactive elements. I envision inviting viewers to participate in ongoing art pieces, fostering a collaborative and immersive experience. Photographing most of my body of work in this outside area for assessment aligns with this broader exploration of connecting the studio with the external environment.

CONCERNING THE LEARNING OUTCOMES IN THE ASSESSMENT CRITERIA

In terms of knowledge, I build a comprehensive understanding of making and skills needed to weave nests and other objects to be used in an installation/exhibition of my work. I showed an ambitious amount of work in my body during the course. I saw them informed by my learning and research about New Materialism and Agency ideas and different materials to be used. Through making work, I explored new materials and discovered outcomes that led to new possibilities in my practice. Nests developed into a broader level of understanding human and non-human needs for safety and containment, as well as exploring this space where human and non-human meet and ideas of human scale were explored.

To apply theoretical ideas, I researched many artists and used opportunities for crit sessions around the relationship between the making and research. I see myself as an artist focused on exploring materials and the connectedness between human and non-human. My intentions have been shared by continuous visual documentation of my making and using photography to capture the connections in my blog writing and on social media platforms such as Instagram and Facebook and student platforms (padlets, group workshops, silent crits) within the university. I am responsible for making social media communications for the OCA EU student group. This has helped me connect with other contemporary artists and share and learn from them on this platform and at our monthly informal and formal training sessions.

Bibliography

Ingold, Tim (2000) The Perception of the Environment Routledge Press. At: https://sfcmadrid.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/ingold.pdf. (Accessed on 18/12/2023).