THE PUBLIC ENCOUNTER WITH WORK

I presented the wire work as an installation called Hotel Kalahari 2024 to keep it focussed on the themes around the nest and where my story originates, personally and physically. Having had an academic speaker who researches the sociable weaver bird gave the work a contextual background about these nests and birds in nature. I suggest setting the tone for my external-facing project by reflecting on O’Doherty’s observation: ‘Every studio has to have some traffic with the outside’ (O’Doherty, 2007:21). O’Doherty’s remark highlights the interplay between the studio and the outside world, and this idea can directly inform my plans on how to transition Hotel Kalahari into a new exhibition space. The focus shifts to how it will interact with and is transformed by its placement.

Living on a farm and doing profoundly personal work that connects strongly with the natural world was the main reason for my exhibition in a barn here on Langvlei Farm. It was accessible from town (6km) and close to Cape Town and surrounding suburbs to invite friends and local connections. A big part of this is the thankfulness that I have reached the end of my studies, which must be celebrated with friends and family. I am motivated and optimistic that this space will also suit my plans concerning future workshops and small exhibitions after residencies or working with other invited artists here in my space.

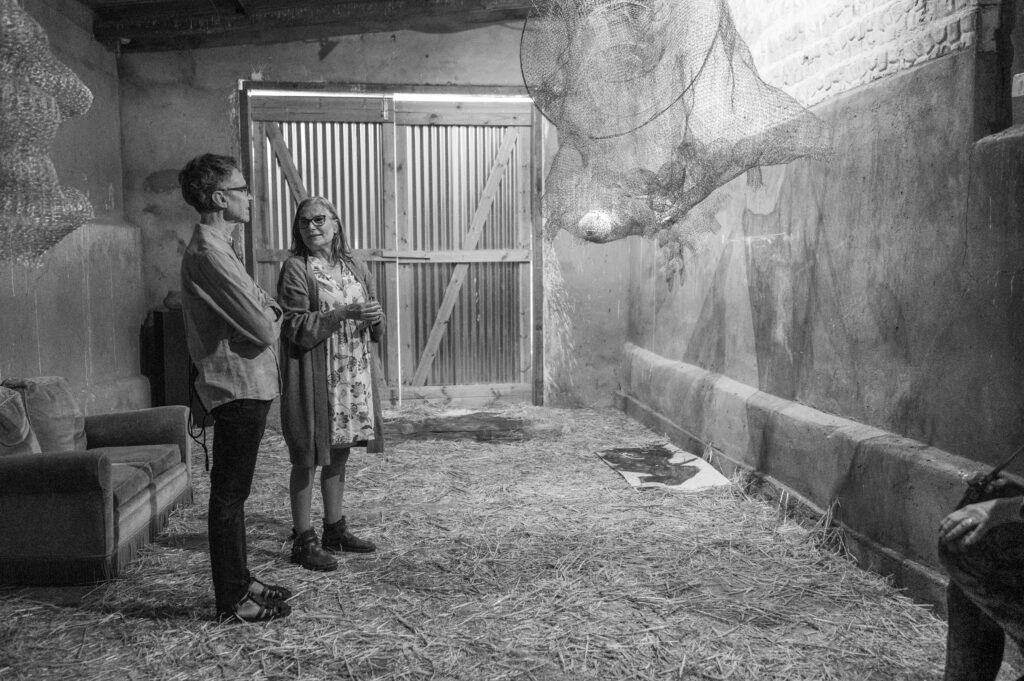

Reading Obrist and O’Doherty earlier in my research and being influenced by the opportunities to use space as a Heterotopia hugely influenced my choice of the barn as my exhibition venue. Having had a chance to study the sociable weaver birds and their nests in nature, as well as being given access to research, such as the articles published by the FitzPatric Insitute and the University of Cape Town, by the invited speaker, was another big motivation to see this space ‘for generating dialogue, creating relationships, and fostering new understandings..’ I believe the barn was that ‘junction’ my work and I needed. (Obrist:2015 ) In earlier discussions around learning outcomes, my tutor encouraged me to develop a broader context for my work, which I think has come together during the exhibition. The exhibition space allowed me to consider professional contexts, such as engaging with and how viewers will experience the work.

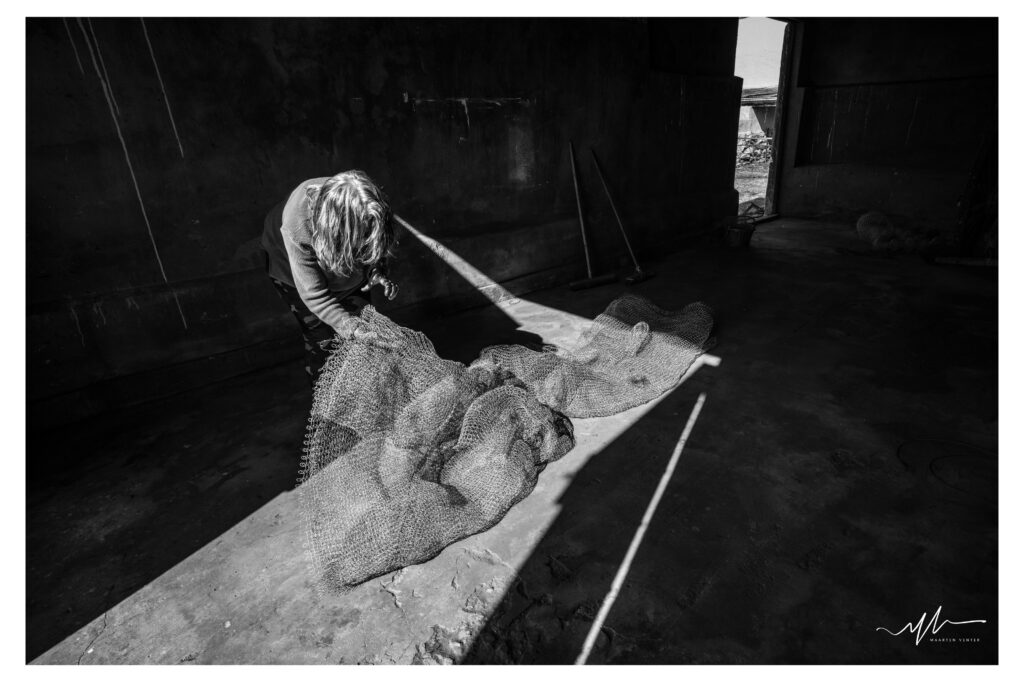

Hotel Kalahari represents the culmination of a deeply reflective process that engages personal narratives and broader contextual frameworks. By making, presenting, and contextualising my work, I have explored and synthesised historical and contemporary approaches to fine art while grounding my practice in personal experience and theoretical inquiry. Ruth Asawa’s meditative weaving process provided a foundational influence, particularly her ability to transform industrial materials into organic, flowing forms. My wire nests echo her approach while engaging with distinct thematic concerns of care, loss, and ecological resilience. My nests are not just physical structures but symbols of resilience—testaments to the human capacity to weave something tender and hopeful even from the most challenging materials. The exhibition’s success lies in fostering a dialogue between the work, the space, and its viewers. Feedback from audiences revealed a shared emotional resonance, with many reflecting on themes of loss, care, and interconnectedness. During the days up to the event, I was always struck by this experience and the work in the space. Taking smaller groups or single visitors through the space after the event confirmed this intimacy with the space and work. The audience engaged with the work within a tactile, intimate context, surrounded by hay and the texture of the space itself.

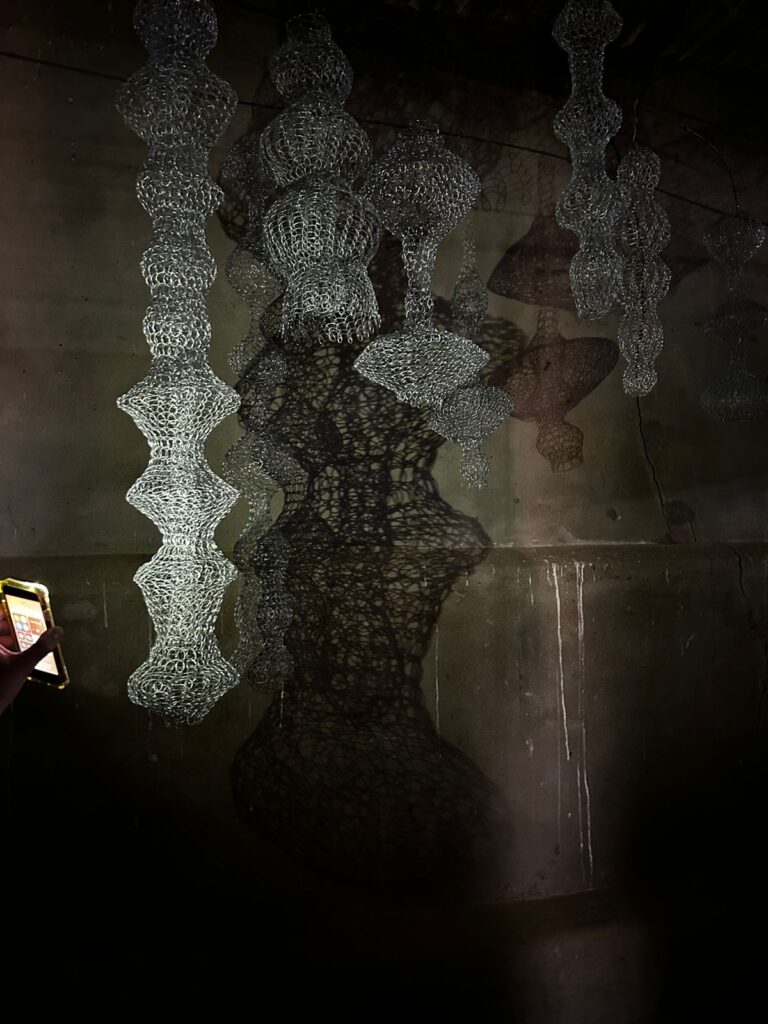

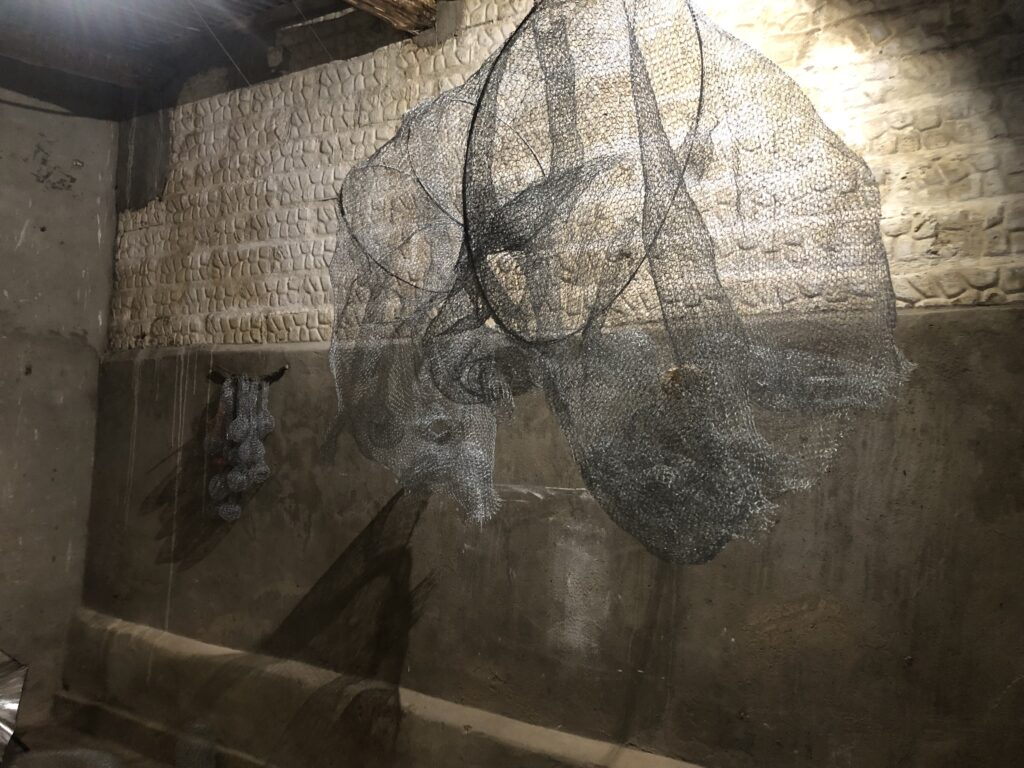

Placing my suspended wire nest and other works within this space blurred the boundaries between art and environment. The interplay of light and shadow became vital, expanding the sculptures’ meanings and inviting the audience to engage with them physically and emotionally. Here, the barn functioned as a heterotopia—a space that, according to Michel Foucault, simultaneously reflects and disrupts societal norms. This heterotopic framework deepened the thematic resonance of my work, underscoring ideas of community, resilience, and belonging within liminal spaces. This has emphasised the importance of contextual research in shaping my creative decisions.

In my Research part of this Level Three course I was strongly influenced by key thinkers, Karen Barad, Posthumanism and Jane Bennett, Material Agency. I see objects and spaces not as passive but as they possess agency, influencing our perception and meaning-making. It was always my thought how the environment participated in the work’s presence. In a new space, walls and sounds will influence the work.

By integrating the insights of Obrist, O’Doherty, and Foucault alongside artistic and ecological influences, I have developed a deeply personal and contextually rooted practice. I aim to continue expanding these connections, exploring how site, material, and narrative can further enrich my work and its impact. Discussions with local curators and gallerists encouraged me to keep the work as one installation. I plan to exhibit it later in 2025 at a ‘new’ venue (still to be identified) in town. The above reflection is what I can take forward when I look at a different space to exhibit the work. The immersive work has conceptual depth to enrich exhibitions and foster audience engagement.

Questions I do need to consider are:

- How can the work adapt to different scales and proportions in outdoor or indoor spaces?

- Will the curatorial strategies preserve the works’ connections to ecological and personal themes?

- How will the audience’s perception of the work shift based on the site and its context?

Site-specific art inherently adapts to and dialogues with its environment. Earlier in my studies, I remember that Kwon argued that the meaning of a work is contingent on the space it occupies, evolving as it moves or is recontextualized. (This is what my tutor kindly reminded me earlier in the course) Reimagining Hotel Kalahari in a new setting could frame the space as a heterotopia—offering a reflective or transformative experience. For example, in an urban gallery, the nests might serve as a counterpoint to industrialized surroundings. At the same time, in an outdoor location, they might blur the boundaries between natural and human-made worlds.

Galleries can constrain movement; when I started suspending the work at various heights and considered pathways that guide viewers through the installation, I tried to imagine that in a vast white cube space or outside in a natural environment. Engaging the audience with interactive or participatory elements could maintain the communal and tactile experience of the barn. The barn I used is not very big (4 x 9m), and visitors had to wait to enter on the opening evening. There was an outside ‘nest area’, made with hay where people could sit as well as interact with a few works that were placed there.

A friend shared this photo (Fig. 4) taken during the opening event. I love how she interacted with the work, touching and moving around it and asking her husband to make this a photographic memory, which she later shared with me. The visual also shares the floor covered in hay, and the irregularity of the walls shows the shadow play. It shares something intimate – a personal experience of space. To me it makes me agree with O’Doherty:

“With the intrusion of installations, video, and the rest, the white cube has become increasingly irrelevant.” (O’Doherty, 2007:40)

In my reflective notes to myself, I kept a quote in the study material made by H Warburton close to my heart:

“One of the things I often find people don’t expect, when exhibiting or installing their own pop-up exhibitions, is how long things can take and the need to thoroughly plan ahead. A show can be turned around in just one day, but making sure that time limitations don’t negatively impact on the final presentation is paramount. With every project I’ve completed, I’ve found the team delivering it, are central to its success or failure and that it is a worthwhile use of energy to ensure individuals are in sync, reliable and assertive and that you work with those who can supplement your own skills.”

The curation was driven by myself. With the support of my husband, close friends and family, whom I could enlist with tasks and responsibilities around catering and practical issues, I could manage organising the event I planned. I had a small budget and kept a firm watch on how I spent it. I had one helper to assist with hanging and moving the work and equipment. As a family, we like entertaining with food, love our home, and have the benefit of excellent summer weather to rely on. The atmosphere was rural, and our homestead had lovely views of the dam and surrounding mountains as the sun gradually set. I intentionally planned the opening event to be early evening as I wanted the visitors to experience the shadows within the space and enjoy the calmness of the farm after a day’s activity. The wine was from the local cellar, and the snacks were homemade. (did I ever tell my tutor that we bake sourdough bread and have had a starter plant for years?)

Fig. 4 Below is a video of guests arriving.

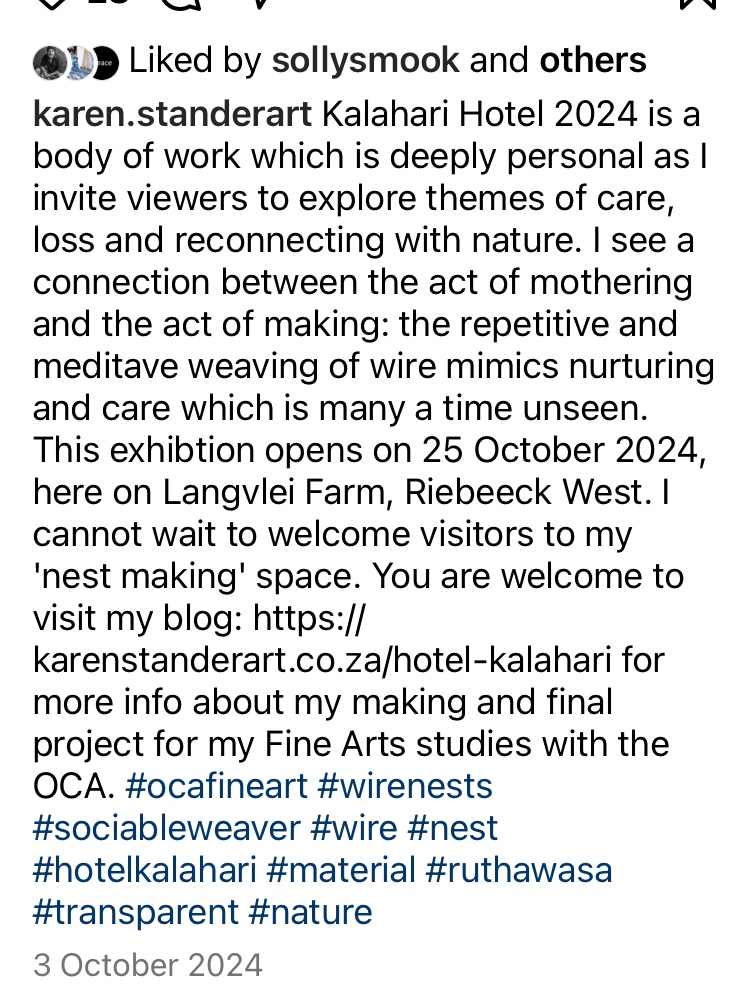

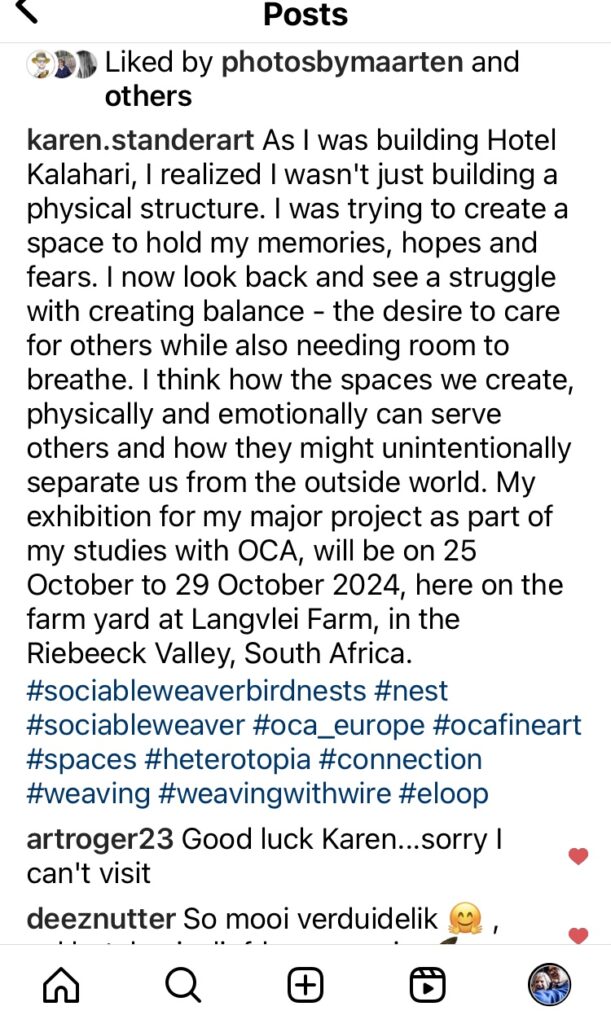

Reflecting on how I used social media and the marketing material leading up to the event is essential. I did write about this in earlier blogs, but to put it in context, I used a save-the-date announcement to start the marketing/reaching-out part of the exhibition. Below are images of posts I shared in early October 2024. In total,l I shared 12 posts over the 8 weeks leading up to the opening event. Almost 90 people attended the opening event.

Below are screenshots and images of visitors’ videos and photos taken during the opening evening and the short speech by Prof. Thomson from Cape Town University’s Fitz Patric Institute for Ornithology.

I invited a knowledgeable academic in the field of research on the sociable weavers to give the visitors an informed overview of the nests in nature and share anecdotes of his interaction as a scientist with ideas of cooperation and care in nature. I have a video to be shared, which gives an impression of the opening and the short talk by Prof Thomson.

The choice of exhibiting in the barn on the farm was not incidental but intentional, rooted in a desire to create a dialogue between the work, its environment, and the audience. Reflecting on Hans Ulrich Obrist’s idea of exhibitions as storytelling tools, I saw the barn as more than just a backdrop; it became an active participant in the narrative. The imperfections of the space—its hay, dust, and shadows—made the work feel alive, evolving in its context. This approach directly contrasts with the sterile neutrality of the “white cube” described by Brian O’Doherty in Inside the White Cube. O’Doherty’s critique of the white cube’s privileging of pristine art objects over material interaction encouraged me to embrace the barn’s rawness, challenging hierarchical norms of art presentation.

Below are some of my favourite moments.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Fig.1 Venter, M. (2024) Shadows [Photo taken with the light of cellularphone] In possession of M Venter: Riebeek Kasteel.

Fig. 2 Venter, M. (2024) Black and White [Photo, wire installation] In possession of M Venter: Riebeek Kasteel.

Fig. 3 Lottering, C. (2024) Enchanting Encounters [Photo] In possession of: C Lottering: Oudtshoorn.

Fig. 4. Stander, H. (2024) Panoramic view of Guests arriving [drone footage] In possession of: H. Stander: Riebeek West.

Fig. 5. Stander, K. (2024) Instagram Post 1 [Screenshot] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West, South Africa.

Fig. 6. Stander, K. (2024) Instagram Post 2 [Screenshot] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West, South Africa.

Fig. 7. Stander, K. (2024) Instagram Post 3 [Screenshot] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West, South Africa.

Fig. 8 – 11 Stander, G, (2024) Screenshots [Video stills] In possession of: G Stander, Durbanville.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Obrist, Hans U. ( 2016 ) Ways of Curating. Farrar, Straus and Giroux read on Kindle

O’Doherty, Brian. (1976) Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space. The Lapis Press, San Fransico. At: https://monoskop.org/images/2/29/ODoherty_Brian_Inside_the_White_Cube_The_Ideology_of_the_Gallery_Space_1986.pdf

PRESS STATEMENT

I was considering using the Press Release I wrote earlier in my separate blog for the exhibition of my work in October 2024. This can be viewed at https://karenstanderart.co.za/press-release/. However, after the exhibition, I re-considered the statement and focused on the following for the assignment.

- Be precise.

- List what works will be on view, describe what they look like, and how they fit into the artist’s practice.

- Include a short artist bio highlighting the artist’s career and mention forthcoming shows and projects.

- Optimize it for legibility on mobile – all my communication. Went out on social media and WhatsApp.

Karen Stander, a local artist in the Riebeek Valley, is hosting her major project for her Honours studies in Fine Arts, during October 2024 in a barn on the farm, Langvlei, where she resides with her husband, Tienie Stander. The opening event will be on Friday, 25 October, at 18:30. The work is part of a more significant body where the artist explored wire as a material.

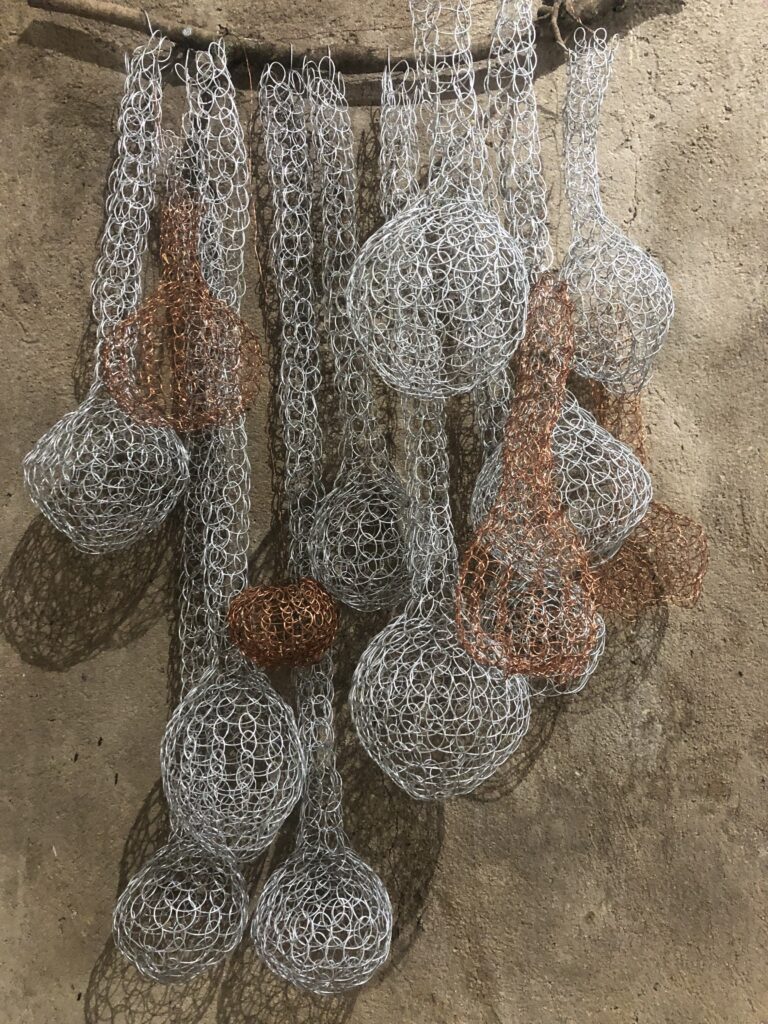

Visitors will be invited into a rugged barn where the work is presented as an installation called Hotel Kalahari 2024. The work refers to the massive nests built by sociable weaver birds and explores the layered themes within nests as places of safety and confinement. These weavers do not weave their nests but stack them. The technique of making the wire nest incorporates using continuous wire, much like a line when drawing, and interlocking loops of wire. As the wire is looped, the artist creates shapes and focuses on form and how light will play through the work. This becomes a meditative process of making.

The work, installed as hanging from the roof trusses of the barn, has the intention to be an experience of interaction with light and shadow. More than 20 organic forms remind the viewer of the work of Ruth Asawa, who inspired Stander to work with the wire looping technique, hanging from the roof at different levels as a group. Viewers can interact with and walk around the work.

In the centre of the barn, you encounter a suspended lump of wire hanging from the trusses, and on a closer look at the underside, it is unexpectedly filled with smaller nests. Viewers are invited to interact with the work. You can lie on your back or sit on the couch. You might feel like looking through the nest or putting on headphones and consider that you have been connected with the little social engineers who make these huge nests. The sounds of the sociable weaver birds are played in this area.

PRACTICE STATEMENT

According to Williams, the Practice Statement should be tailored to inform art professionals, such as curators, critics, and collectors, as well as for professional contexts, such as gallery submissions, grant applications, and residencies. It is about the artist’s trajectory and overarching vision. This implies a broader focus of the artist’s work and creative process. One could consider writing about recurring themes, methods and conceptual approaches across multiple works or projects.

FINAL PRACTICE STATEMENT

Karen Stander’s artistic practice is characterized by an exploration of material agency, spatial relationships, and the transformative potential of art to navigate loss and foster connection. From her studio in the Riebeek Valley, South Africa, Stander creates large-scale wire sculptures inspired by the nests of sociable weaver birds—ingenious communal structures embody resilience in the harsh Kalahari Desert. Her work reflects the interconnectedness of the human and natural worlds while reimagining notions of care, survival, and adaptability.

This exploration of materiality has been central to her practice. In prior installations, Stander worked with feathers, creating evocative pieces that invoked fragility, flight, and transition. A later project saw her crafting a steel wing armature—a powerful symbol of both strength and aspiration—further developing her interest in dualities such as groundedness and transcendence, containment and openness. These themes recur in her work, forming a throughline of inquiry into how materials and forms embody human resilience and connection.

In Hotel Kalahari’s monumental wire nest installation, the interplay of light and shadow animates the work, creating shifting patterns that echo the fluidity of human experiences. Historically associated with control and division, industrial steel wire is transformed into woven forms that convey fragility and strength, openness and containment. This material choice underscores her practice’s recurring themes: reclaiming narratives of separation and imbuing them with care and connection.

Stander’s practice is deeply personal, shaped by her own experiences of grief and healing. Following the loss of her youngest son, the repetitive act of weaving wire became a meditative process, a way to transform pain into meaning. This process mirrors the instinctual and collective building practices of sociable weavers, whose nests inspire her work as metaphors for survival, care, and community. Each wire loop embodies intention, creating spaces that are as much about resilience as about vulnerability.

Drawing on Michel Foucault’s concept of heterotopias, Stander’s sculptures function as spaces where multiple narratives and histories converge. For Hotel Kalahari, the barn on her farm became a crucial collaborator. Its imperfections—marked by hay, dust, and the passage of time—interacted dynamically with the industrial wire forms, creating a dialogue between site and object. This contextual relationship invites viewers to consider how spaces shape the meanings of art and influence engagement.

Inspired by Hans Ulrich Obrist’s idea of exhibitions as storytelling tools, Stander views her practice as an ongoing dialogue between work, audience, and environment. Her vision for future exhibitions involves expanding Hotel Kalahari into outdoor landscapes or urban spaces where new spatial relationships could emerge. Each iteration would reflect the recurring themes of transformation and resilience and her commitment to engaging with local communities and environments.

Through her practice, Stander asks: How can materials, imbued with division histories, be reclaimed as symbols of care? How do natural or constructed spaces shape narratives of connection and survival? In both material and theme, her work offers a meditation on the human capacity to create meaning, foster connection, and weave hope from even the most challenging materials.