Introductory thoughts

During our tutorial session on Part Two of the work, my tutor suggested I delve into Foucault’s ideas on Space and Heterotopias. This was a transformative moment to understand how spaces function and how this will deepen the theoretical underpinnings of my practice and assist in creating a more impactful exhibition. Regarding curation strategies, I was also looking at the work of curator Hans Ulrich Obrist. I could access pdf documents, video talks, and links in the study guide. My studies and experience suggested that knowing how I present my work and where I exhibit the work is particularly important. The study guide presented interesting spaces and ideas.

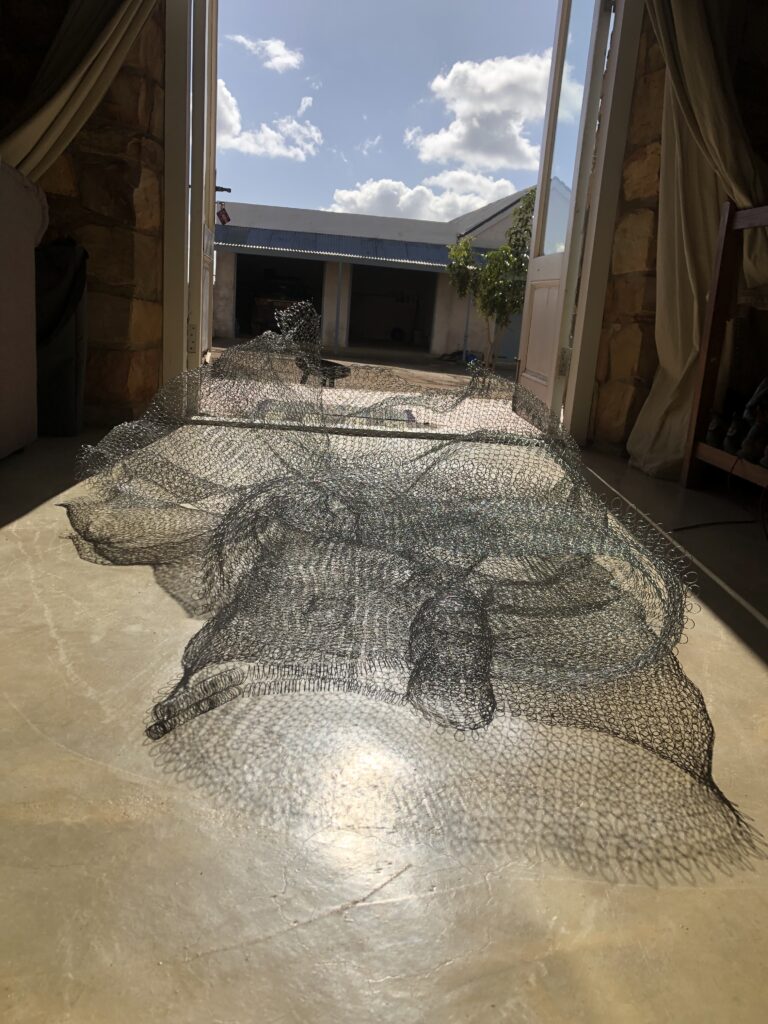

I was able to show my wire work with the NGO where I facilitate art classes for young children. I did not want to share my nest on this occasion – being influenced by Obrist, I wanted to work more on the space and experience of being with the work. I also felt it was still a work in progress. Instead, I made a considerable wire wing in 5 separate pieces, installed in the ceiling of the exhibition space, from which works done by the kids in interactive workshops would be suspended. Below is an image of that installation – I share it as I realise it shows the influence of the work of L Prouvost, but it also had that immersive experience with the work in the space: it was placed and shared with the audience, who was also invited to touch and interact with the work, as well as make work during the daily workshop sessions. The installation was almost alive – it grew over the 3 days of the exhibition and workshops, as more work were added after the workshops.

By looking at broader contexts, I see this blog as investing in my final presentation of my body of work and its curation. I have to consider the type of place of an exhibition, external encounter and/or public presentation. What might a ‘space’ mirror or reflect in the work, and what questions and/or connections might it foster? I looked at conversations the exhibition could open up, hopefully, a new and meaningful dialogue between the work, myself, and the audience. Hans Ulrich Obrist talks about junctions and the exhibition space being like a toolbox (Ways of Curating, 2015). What stuck most with me is that Obrist examines why making exhibitions matters. Exhibitions become dynamic “junctions” where ideas, contexts, and experiences intersect and evolve. I would love for this to play out in my exhibition! His perspective on an exhibition as a toolbox challenges the traditional notion of the exhibition as a static showcase. Here, it highlights its active, participatory role. It suggests that exhibitions are processes rather than finalities, where the curatorial approach can frame, activate, and even transform the meaning of the work.

Below is a summary of my research after I read articles on Space by Foucault

- Foucault sees space as social, cultural, symbolic, political, and functional. It is not just a positivist scientific observation. It becomes ideas about how we reflect on our culture.

- He argued that spaces are not neutral but imbued with power and social meanings.

- The concept of heterotopia describes real places that exist outside of ordinary spaces but are still connected to them.

- Heterotopias are distinct from utopias, which are idealised, imaginary spaces.

- Heterotopias serve specific functions and have meanings within a society.

The concept of heterotopia describes real places that exist outside of ordinary spaces but are still connected to them. That connection I understand is that these spaces are localizable, like in the attic, at the bottom of the garden, and in art. Heterotopias serve specific functions and have meanings within a society. Heterotopias are worlds within worlds, and they suggest that composing incompatible spaces is vital; heterotopias can bring together incompatible spaces in the ordinary world. According to Foucault, heterotopia overthrows the rules of the real and makes other laws – push and pull.

Foucault presented six principles of heterotopias.

- The first principle is that every society has heterotopias of some kind and delineates two main categories: crisis and deviancy.

- The second principle is that heterotopias are adapted according to new functions required by society.

- The third defines heterotopia as multi-faceted.

- The fourth principle is that heterotopias exist in time slices with a clearly defined beginning and end.

- The fifth principle is that ‘heterotopias always presuppose a system of opening and closing that both isolates them and makes them penetrable’.

- The final principle is that heterotopias ‘have a function concerning all the remaining space.

Application to my work

I understand that heterotopias in art happen when the artist creates a physical space separate from the outside world. Stagers of Heterotopia provide visitors with a place to escape and explore within. As an artist, I aim to create a Heterotopia where visitors can experience something profoundly and emotionally. My work can be an installation, and I am intrigued by using space as a form of ‘interiority’.

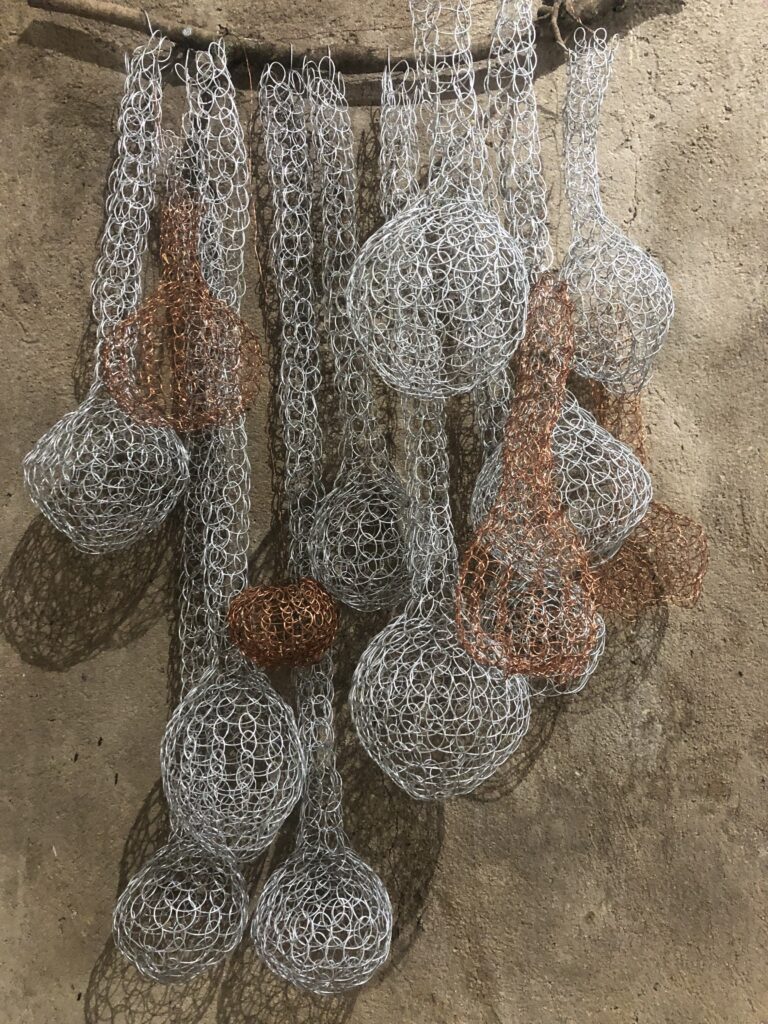

By creating a wire nest installation, I can present the nest as a heterotopia if it embodies a space that reflects and challenges the viewer’s perceptions of home, safety, and confinement. The nests could juxtapose the natural (nest) with the artificial (wire installation), creating a space that speaks to protection and entrapment, mirroring societal tensions. By choosing wire, a material associated with barriers and protection, I can produce a space that critiques and comments on societal norms and power structures, engaging viewers in thoughtful reflection to contemplate the intricate balance between safety, division, and confinement. I realized the nest could lie on the ground, not necessarily hang on a wall – use ‘place’ to position the work. It allowed me to explore how different contexts influence interpretation.

The image above reminds us of spatial theories ( Foucault) and Postmodernism – a heterotopia that emphasizes spaces within and outside societal norms. Postmodern approaches acknowledge the layered meanings of spaces and their histories. I learned that this reaction took on multiple artistic forms by the 1950s, including Conceptual art, Minimalism, Performance art, Video Art, and Identity art – spaces and histories were acknowledged for their layered meanings.

The nests’ relational aspect is crucial, relating to the viewer’s experiences and perceptions of space, safety, security, attachment and confinement. I can explore how context affects their interpretation by placing the nests in different environments (public spaces vs. galleries). I am considering having my exhibition in a barn on the farm. I can use the opportunity to display my wire nest for viewer interaction about the space in which it is displayed.

Controlled lighting will emphasize shadows and the illusion of flatness. In this environment, and being conscious of the narrative capacity of the site, it acts as a bird nest by bringing the inside to the outside – the viewer can see into the nest, and the breeding chambers and tunnels are placed on the outside. I can use soundscapes of bird songs to create an auditory sense of nature, contrasting with the visual confinement of the wire.

I strive to create spaces that offer solace, provoke thought, and foster a deeper understanding of our shared need for safety, connection, and compassion. Am I asking my viewers to see beyond the ordinary? Is this not what art wants to do – to question our reality and what we see as usual?

This method aligns with Hans Ulrich Obrist’s ideas on exhibition-making as storytelling, emphasizing process and context. For Obrist, curatorial practice involves activating spaces to enhance the dialogue between the artwork, the site, and the audience.

My work carry cultural and symbolic meanings. While nests in nature symbolize home, safety, and nurturing, they transform into a symbol of confinement and restriction when made out of wire. This juxtaposition highlights space’s cultural and symbolic layers, showing how a simple object can have multiple, often conflicting, meanings based on its material and context. In nature, the materials used by birds speak to the landscape, so you can identify the bird that made that nest. I also know that the natural landscape is changing and birds must adapt, even when finding nesting material. The nest has become a representation of natural forms, but I also hope it is an intricate commentary on the human condition. Will it challenge viewers to consider the complexities of care, confinement, and the ephemeral nature of life? Through this work, I strive to create spaces that offer solace, provoke thought, and foster a deeper understanding of our shared need for safety, connection, and compassion. A bird’s nest has areas of invisibility – I show everything with my wire nest: as a heterotopia, there is a visual exchange between the inside and the outside of the nest. The wire shows this potential of seeing the nest differently – seeing the inside. While nests traditionally symbolize safety and nurturing, wire transforms them into sheltering and isolating spaces.

As I work on the nest, the object becomes heavier and more challenging to move and manipulate. I know how objects morph into shapes and forms due to material ‘plasticity’. I increasingly feel the nest must be suspended when I consider exhibiting it.

Enhancing Conceptual Framework by looking at contemporary artists who work with space

Here, I looked at the work of Laure Prouvost in a separate blog. (https://karenstanderart.co.za/laure-prouvost-ideas-to-consider/). Much later, after the exhibition, I realised that in future, I could use performance to explore entrapment/protections around the nest. This will be part of the Project Plan after my studies.) In the image of her installation called Above Front Tears Nest in South, below, I saw that the nest could represent a place of emotional refuge or where memories and personal histories can be or are (?) woven together. Her work shares a theme where home, security and nurturing happen.

Rachel Whiteread creates sculptures that cast the negative space around or within objects, such as her famous piece “House,” a concrete cast of the interior of a Victorian terraced house. Her work interrogates the spaces of everyday life, often highlighting the absence and presence in domestic spaces, which can be linked to Foucault’s ideas about the function and meaning of different spaces in society. I like that her work also connects to ideas around absence and loss and how she explores a home as a place of domesticity, which align with my nests as symbols of shelter.

I also look at the work of Chiharu Shiota, where thread installations envelop objects and spaces as they become immersive environments. Viewers are invited into the work – stepping into a web of physical and emotional entanglement. These installations invite viewers to enter and experience a physical and emotional space. Shiota’s work transforms spaces into heterotopic environments that blur boundaries between interior and exterior, past and present, presence and absence.

In his work, Uncertain Journey (2016), below, red threads fill a gallery space, enveloping skeletal boat structures. The boats symbolize journeys—literal and metaphorical, while the web of threads represents the complexities of life, relationships, and emotional entanglement.

Reflecting on the learning around Heterotopias and nature where the real nests occur

This research contributes to a theoretical outlook on my work. I do not want to ‘reproduce’ nature but want to push towards themes that highlight protection versus confinement and look at the idealized secure environment versus chaos in the world. I can create conversations by playing with scale, materials, and the nest’s structure. Heterotopias have provided a valuable framework to challenge perceptions around protection and confinement. I will have the opportunity to curate my work and think about the etymology of curating, coming from the Latin word curare, which implies to take care. Over time since the Roman times, what was cared for changed – by the 19th century, it meant looking after collections of art and artefacts.

In my research on the sociable weaver nests, I learned that entrance tunnels into the nest can be up to 25 centimetres long and 7 centimetres wide. The inside of the nesting chambers are round and 4 to 15 centimetres in diameter. There may be 5 to 100 nesting chambers in a single sociable weaver nest, providing a home for 10 to 400 birds! No other bird species build such a communal home. The interesting fact that other birds nest inside or on top of these structures made the idea of the nest as a heterotopia even more legitimate. I have a list of birds who live inside these nests.

The South African pygmy falcon relies entirely on the sociable weavers’ nest for its own home, often nesting side by side with the sociable weavers. The pied barbet, familiar chat, red-headed finch, ashy tit, and rosy-faced lovebird frequently find comfort in the cosy nesting chambers, too. Researchers showed that communal nests of sociable weavers provide thermal benefits to weavers and heterospecifics alike, creating a more optimal environment for breeding. Vultures and eagles often roost on the nest, and owls use the top as a nest.

Why are weavers willing to share the huge nest they worked so hard to make? More residents mean more eyes keeping a watch for danger. And the weavers often learn from the other birds where there are new sources of food.

In a podcast with research group leader, Dr Robert Thomson, from a local university, I heard the reference of the nest to a hotel. The design of the nests, which allows various species to coexist, reflects the balance between isolation and accessibility. In ecosystems, do this balance ensure that no single species dominates, promoting a healthy environment? I contacted dr Thomson to ask permission to use his term, Hotel Kalahari, as the theme for my planned exhibition of this body of work. The nests in nature are located in arid areas. The nest is a hotel for other species, such as birds that roost on or in or even breed in them.

By applying Foucault’s concept of heterotopia to contemporary museums and galleries, we can better understand how these spaces function as repositories of art and culture and as dynamic, multifaceted environments that reflect, challenge, and shape societal norms and values. This framework allows for a richer, more nuanced analysis of the role of museums and galleries in contemporary society, highlighting their potential to act as spaces of reflection, engagement, and transformation. Thinking, a visual language – to go beyond, create another possible world – the field of imagination, transformative potency. A bird’s nest has areas of invisibility – I show everything with my wire nest: it can be a heterotopia where there is a visual exchange between the inside and the outside of the nest. I use wire to show this potential of seeing the nest differently – seeing the inside.

Consolidating the notion of separateness and securing the spatio-temporal boundaries, the fifth principle is that the heterotopias have a system of opening and closing that isolates them and makes it possible to enter them. In society, we constantly navigate the tension between private and public spaces, as well as exclusion and inclusion. By creating an open yet intricate structure, my work can prompt viewers to think about how they engage with others and how societal norms dictate access to different spaces and opportunities. In my research on sociable weaver’s nests, I read about the work done by a group of scientists who have been busy studying a group of nests for longer than ten years.

In the fifth principle Foucault refers to openings which seem to be pure and simple openings, but are generally hiding curious exclusions. Foucault gives the example of the famous bedrooms that existed on the great farms of Brazil and elsewhere in South America as explanation. The entry door, meant for uninvited guests, did not lead to the room where the family lived, but to the bedroom where one could overstay the night. ‘Everyone can enter into the heterotopic sites, but in fact that is only an illusion – we think we enter where we are, by the very fact that we enter, excluded.’ Another example for this type of heterotopia could perhaps be found in ‘the famous American motel rooms where a man goes with his car and his mistress and where illicit sex is both absolutely sheltered and absolutely hidden, kept isolated without however being allowed out in the open. Given above discussion around how the nest is used by other species one do as yourself why are weavers will to share the nest they work so hard to make. One reason could be that there are more eyes watching out for danger, another could be that the birds could learn about new sources of food.

Exhibition space

Thinking about my planned exhibition, I think of using our house or the cottage, a barn and or the farmyard/dam as ‘gallery space’. I can highlight the potential of these spaces for reflection, engagement and transformation. The barn’s role as a site also aligns with Foucault’s concept of heterotopias—“other spaces” that function outside or alongside normative cultural spaces. The barn becomes a heterotopia where traditional hierarchies of art presentation are disrupted, and the boundaries between art, viewer, and environment dissolve. I can cover the floor with hay and allow the natural markings of the space to interact with the artwork. This intentional approach blurs the boundaries between the works of art and its environment, turning the barn into more than a backdrop. It can become integral to the narrative, inviting viewers to engage with the work more tactilely and immersively. I will also look at the critique of the white space by O’Doherty in this part of my discussion as I will use a barn as an exhibition space.

The nests create physical and symbolic spaces, challenging viewers to consider themes of care, nurturing, security, attachment, confinement, loss, and connection. This theoretical framework enhances the meaning of my work, positioning it within a broader discourse on the production of space and the power dynamics inherent in spatial configurations. I started playing with the words habitat and habituation, and as my thoughts developed, I became more aware of the effect of the transformations we made to make the world our habitat. Did we compromise the landscape’s habitability? Is this the challenge of the Anthropocene? While nests traditionally symbolize safety and nurturing, wire transforms them into spaces that shelter and isolate. These nests, viewed as heterotopias, challenge the conventional perception of home as a purely protective space. They reflect the complexities of our social structures, inviting viewers to contemplate the intricate balance between safety, division, and confinement in our lives. Parts of the cultural sphere have facilitated resistance to dominant discourses, while art studios and galleries, dance and performance settings have transformed into spaces within which the order of things is recreated, disrupted and challenged.

While both bird nests and human houses involve intentional construction, the distinction lies in the scale, complexity, materials used, the intent behind their creation, and the broader societal context. The concept of “natural” versus “artificial” is not always straightforward. Birds use natural materials they source in their environment. Still, birds also use other materials in different spaces, sometimes not natural, such as plastic, made-made fibre materials, etc. (Humans use primarily manufactured materials to build, and our houses are bigger and more complex in design, planning and construction.) I wonder about comparing the nest and its protection for its inhabitants and how biodiversity offers resilience against environmental changes. I am aware that studies around these nests also look at the biodiversity compared to trees without nests. Can the wire emphasise the nature of protection and vulnerability and ask us to consider how ecological systems and social norms can protect and expose members to risks?

My wire nest installations draw inspiration from the sociable weaver’s nest, embodying Foucault’s fifth principle of heterotopia. “Heterotopias always presuppose a system of opening and closing that both isolates them and makes them penetrable.” These nests, with numerous entrances pointing downwards from the haystack-type nest and their interconnected chambers, symbolize the delicate balance between isolation and accessibility, protection and openness. Just as the weaver’s nest creates a complex social structure within its confines, my work explores the dynamics of access and confinement, reflecting on the societal structures that govern our lives. Wire as material further emphasizes this duality, with its transparent yet rigid nature, inviting viewers to contemplate the interplay of security, protection, inclusion, and exclusion in our environments.

I also looked at the work of O’Doherty, and by choosing the barn as an exhibition site, I actively reject this “neutral” framework he refers to. The barn is far from a blank slate; it brings with it its own history, textures, and context. The hay, dust, and natural markings interact with my wire installation, emphasizing their materiality and connection to the environment. This challenges the supposed neutrality of the white cube by embedding the work in a specific, lived, and dynamic space. The barn will enforce an inclusive, tactile, and immersive experience for the viewers that reconnects the art to the “messiness” of life. It is not a sterile, sacred space but a site of labour, care, and connection. This invites a more grounded and immediate interaction with the work, fostering a sense of intimacy and accessibility. The barn’s rural setting further connects the work to themes of community, ecology, and the natural world’s rhythms, opening the exhibition to broader social and cultural resonances.

List of Illustrations

Fig. 1 Stander, K. (2024) Breathe, Breeze and Winged Things.[Photograph, Installation] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West, South Africa.

Fig. 2 Stander, K. (2024) Heterotopia: A history of space [Photograph of cleaning the barn to become an exhibition space] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West, South Africa.

Fig. 3 Stander, K. (2024) Nest on floor. [Photograph of Work in Progress] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West, South Africa.

Fig 4 Prouvost, L. (2023) Above Front Tears Nest South. [Photograph, Installation] At: https://moody.rice.edu/exhibitions/laure-prouvost-above-front-tears-nest-south (Accessed 06/06/2024)

Fig. 5 Shiota, Chiaru. (2016) Uncertain Journey [Photograph, Installation] At: https://www.chiharu-shiota.com/uncertain-journey. (Accessed 22/06/2024)

Fig. 6 Stander, K. (2024) Nest chamber group. [Photograph, Installation] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West, South Africa.

Fig. 7 Stander, K. (2024) Collage of Nests. [Photograph, Installation on paper] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West, South Africa.

Fig. 8 Stander, K. (2024) Heterotopia 2: A Barn as Exhibition Space? [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West, South Africa.

Bibliography

Foucault, M. (1967) Of other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias. (written as “Des Espace Autres’) published in Architecture /Mouvement/ Continuité in Oct. 1984 (9-page PDF)

McConnel, Deirdre. (? ) Slices of Time Heterotopia and Counterspace in Art Therapy. Published online At: https://trackchangesjournal.wordpress.com/archive/issue-12-utopias-dystopias-and-heterotopias/slices-of-time-heterotopia-and-counter-space-in-art-therapy/ (Accessed 02/06/2024)

Miloje Grbin. (2015) Foucalt and Space (8 page PDF) In: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320184686_Foucault_and_space/fulltext/59d384a90f7e9b4fd7ffb2c5/Foucault-and-space.pdf)

Kabra, Fawz. (2018) Above Front Tears Nest in South. online In: https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/laure-prouvost/ (Accessed 04/06/2024)

Lowney, Anthony M & Thomson, Robert L. (July 2022) Ecological engineering across a spatial gradient: Sociable weaver colonies facilitate animal association with increasing environmental harshness. Read online article published in the Journal of Animal Ecology Volume 91, Issue 7. Pages1327-1553 at:

https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1365-2656.13688?campaign=woletoc

Obrist, Hans U. ( 2016 ) Ways of Curating. Farrar, Straus and Giroux read on Kindle

Obrist, Hans U. (2011) The Art of Curating. [TedxTalks] At: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gyIVCqf23cA (Accessed 31/05/2024)

Obrist, Hans U. (2013) Do it At: https://curatorsintl.org/exhibitions/18072-do-it-2013 (Accessed 28/05/2024)

O’Doherty, B. (1999) Inside the White Cube, University California Press At: https://monoskop.org/images/2/29/ODoherty_Brian_Inside_the_White_Cube_The_Ideology_of_the_Gallery_Space_1986.pdf (Accessed 20/05/2024)

My artist’s statement after the above research

My wire nest installation is inspired by the intricate nests of sociable weaver birds in the Kalahari, which serve as homes for multiple bird species, each benefiting from the structure in unique ways. This installation reinterprets nature by bringing the inside out—displaying the ‘breeding chambers’ externally and allowing the nest to remain open, potentially inviting viewers to climb inside. The work I am referring to is called, Kalahari Hotel, 2024.

This work embodies Foucault’s concept of heterotopia, spaces that juxtapose multiple, often contradictory elements within a single site. The wire nest combines natural inspiration with artificial materials, creating a transparent and rigid space, symbolizing the duality of vulnerability and protection. The open structure invites viewers to contemplate the delicate balance between isolation and accessibility, reflecting on societal structures that govern our lives.

In nature, sociable weaver nests support biodiversity, offering roosting and breeding spaces for various species. Similarly, my work explores themes of interconnectivity and interdependence, highlighting how different elements can coexist within a single space. This nest becomes a living heterotopia, encouraging viewers to reflect on the dynamics of access and confinement and the richness of biodiversity.

Through this installation, I aim to create a space that transcends its immediate function to reveal more profound truths about community, cooperation, and the complex social structures that shape our interactions. By engaging with this work, viewers can explore the interplay of security, protection, inclusion, and exclusion in our environments, drawing parallels between the natural world and human society.”

More ideas to explore:

The concept for a performance (after Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping, 1981)

I consider how in my writing with a performance around the work (narrating/fiction) will can share this exchange. Can a performance be explored: where I show an attempt to render the nest habitable for humans – safe space or consider how we life an consider permanence and stability in our lives and not always consider change or that things come to an end. Can one extend the boundaries of the nest into the landscape – our way to domesticate or find safety , but also the house could become more habitable by the nature of those who live in it, letting nature come into the house – outward and inward. In a way the space is now not only physical, but also our imagination.

Did I try to ‘domesticate’ a nest?

Can art create a space of unlimited opportunities? Art is the way of connecting all our stories and sharing our humanity. [. . .] I don’t know of other means that do that. (Arianna Economou)