Considering weaving and looping as techniques to make nests: A shift in my practice

This blog started in early January 2024 as I continued working on my practice and considered upscaling the nests and/or painting/drawing humans in or around them. It made me feel like I was sharing drawings and interacting with the outdoor environment. I started to wonder about nests as home and how territory and belonging play a role in human and non-human situations.

Looking back at a drawing I made with an eraser feels like a turning point. I see how my hands try to find the weaving process. It is a search for those lines that intertwine in the making of the nest.

I had been considering my ongoing practice, which looked like it was shifting from drawing to making with my hands. I was also talking about performing drawing as a local artist connected with me, and we started talking about doing work in the future. My idea was to explore a nest as the drawing. I am open to these ideas around performance art and will continue this exploration after SYP studies in early 2025. I knew for now I wanted to work around making 3D nests.

Learning the skill to make

I had a strong need to loop and research methods I could learn. Something in the rigid steel material reminded me of possibilities where learning the technique would help me understand shaping, making, and telling a personal story of motherhood, loss and reconnecting. The practical step was to learn how to do this and start making work. I searched for online workshops and shared my need to know this technique with my peers. In March 2024, I started making the wire nest, which I later titled Hotel Kalahari. By now, I have made a raffia nest after the sociable weaver nests and explored it tactically with a vast wall drawing in charcoal. I visited actual nests in early April, and their communal living and interdependency told me so much about adapting to circumstances and learning from nature.

I searched for the new term knotless (looping) netting and found these images from a 1935 article, “Knotless Netting in America and Oceana, ” by Daniel Sutherland Davidson. It became clear that I had to research Ruth Asawa’s method more.

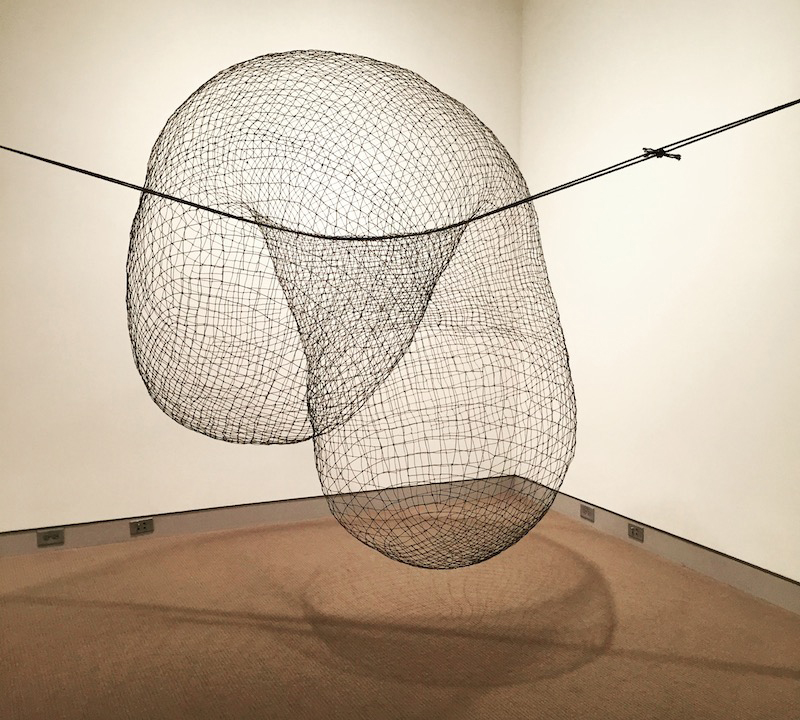

Contemporary artists working with wire

Current artists using the technique were also in my pipeline, so I started following local and international artists/ makers and installation artists on social media to learn about their work, methods, and materials. When I discovered the wire works by artist Anna Hepler, I became aware that my work is also very much based on an intuitive approach, a whole of risk-taking. There is much uncertainty in this making process. Her work, when she explored wire as material, talked to me about the ‘floppiness’, but as she continued to explore the material, new work emerged, which became increasingly abstract.

Artists I follow and who influence my work are Gjertrud Hals (fibre), Racso Jugarap (Wire artist), Anna Hepler (USA), Catriona Pollard (Australia), Kate McDonnel ( UK), Roberta Wagner (Textile), Emma Willemse (Local). I visited the local artist Emma Willemse’s studio to discuss her installation work and ideas for working with loss. I am also grateful for my fellow student group as part of the OCA EU group, where we almost daily share work, do critiques, and share our experiences of making and keeping an ongoing practice going throughout the studies. A fellow group member shared a video of how she looped with wire – this was very helpful, and I could advance my learning.

Fig 7 (video below)

I considered the materials Asawa used: brass, copper, aluminium, iron, and steel wires (Graf, 2022). By mid-February, I was confident I understood the ‘ how to’ of Asawa’s looping technique. I was now ready to buy a more significant supply of wire and decided to purchase agricultural wire from our local agri store. The wire connects to my rural living; it is financially viable and easy to work with. My husband assists in making a much bigger coiling tool, which I can move around whilst working. I bought a roll of 50kg of binding wire from the local Agri store. By early June 2024, I employ a studio assistant to do the coiling – I pay her per kg and have more time to focus on my making and working on the idea of a huge nest for my exhibition.

On her making, the following was written about Asawa in Interior Design, September 2018: “The repetitive, mechanical aspect of Asawa’s technique may have troubled critics, conjuring baskets and fish traps, but I would argue that her art occurred precisely at the intersection of the mechanical and the organic, and so addressed a central problem of early postwar modernism. Rumpelstiltskin-like, Asawa spun living forms out of base materials. She transformed a mechanical process into a richly organic oeuvre, echoing and marking the cultural rebuilding and renewal process that followed the Machine Age and World War II.”

I value that Asawa mastered her material – the idea of repetition implies continuous working, exploring, and learning. My research showed that her initial classes in working with paper laid this foundation for understanding your material. Her studies at Black Mountain College encouraged her to ‘abstract from the material’ rather than to enforce your ideas on the material.

I later found an online article in Panorama, which describes her making method so well:”The principal technique in her best-known sculptures is derivative and simple in concept and painstakingly manual in execution, employing an interlocking looped-wire construction. With this repetitive technique Asawa made sculpture built up from repeated formal units that inevitably display subtle differences. Difference achieved through repetition might, in fact, be as appropriate a summary as any of her achievement, and as evocative of its fundamental humanity.” (Klein, 2019)

The first successful work

My thoughts on the making process so far are:

- It is hard on my hands, and

- the trick is to keep tension in the weaving, allowing the loops to be open for the next row of loops to ‘click’ in.

- The wire is hard to control; with that, I mean pulling the wire to a desired tension, as this is the ‘trick’:

- working on keeping the loops the same size. I see the need for sharp, rounded tools to assist in this pulling and even pushing the loops into the previous row. (I later mastered this by keeping the gauge consistent through the dowel sticks I used to coil it)

- I needed a dowel to coil the wire onto.

- I need pliers to cut, bend or join the wire.

- Art versus craft and ideas around aesthetics came to mind

- It is a time-consuming process but can be meditative as it becomes easier to master the process

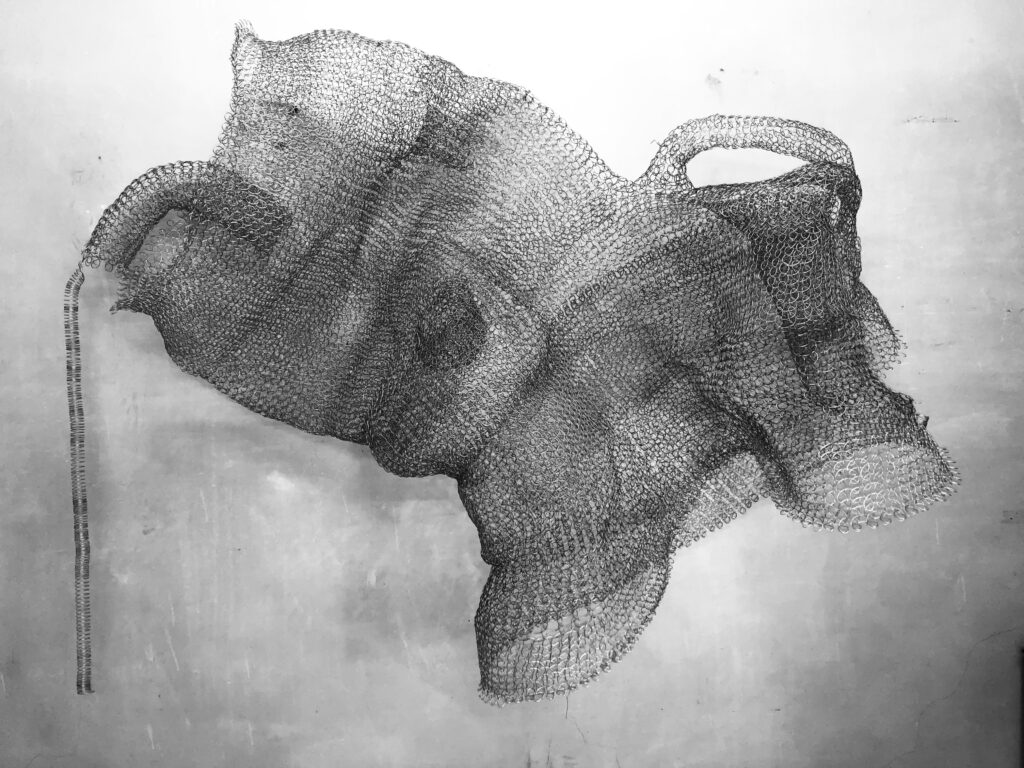

WHY a Nest?

I questioned why I liked working with wire and found myself at this place of learning weaving skills with wire when I could go and paint or draw instead. It must lie in how seemingly inert materials give me an experience of connection with making, and on a deeper level, I was going through a tumulus emotional crisis after my youngest son’s death. How one makes these e-loops that form a pattern, work with interconnectedness and evoke emotions ranging from wonder/ joy to contemplation/introspection. When I think about the shadows these works cast, I see forms that are not static: there is a visual rhythm and sense of movement which change throughout the day as light moves around and in the work. I learned much about transformative qualities in the wire (material). Initially rigid and lifeless, the wire can be manipulated to embody fluidity and movement. The transformation of the material contributes to perceiving the forms as dynamic and alive.

I later go back to think about ideas for making – about beauty and being in awe of nature. The fact is that a nest is primarily a temporary idea/thing. Things/life constantly change; they transform into something new over time, and with it, they are carrying layers of past lives. It is as if something in the making relates to interconnectedness, which evokes emotions ranging from joy to introspection. My nest is not just a physical structure; I am trying to create a space to hold my memories, hopes and fears. I wanted to construct something that could have and protect, but I began to see how these protective spaces sometimes feel like barriers – keeping the world out and, sometimes, keeping me locked inside. I think about how I protect myself. I need a refuge, a safe space, but it might unintentionally separate me from the outside world. I think about myself working in a studio on a farm – I prefer this space and tend to ignore my connections with the outside world. This space could also be a refuge, but I need to interact with others – my course asks questions regarding connecting with peers and my local opportunities. I learned about my need to feel safe and share my emotions – my making is essential.

Louise Bourgeois discussed artmaking as a way to process and transform otherwise intangible feelings. My subject is not the wire but the ideas and emotions it contains: care, loss, and resilience. Each object/nest becomes a vessel for these, offering me a curative space for healing through creation. For Louise, spiders became a recurring motif, symbolising her mother: protective and patient, yet often misunderstood. I have found my symbols in nests.

I like to view my work not as finished constructions but as an ungraspable moment of transformation. I explore this space, but it is still a blurred area where meaning and the work/ concept meet. In the following months, I learned that these nests were not just physical structures I made; they became a space for emotional reflection. Each loop became an act of resilience, and something cold and industrial turned into something fragile and vulnerable.

By July, the nest had become a very interesting work – I liked to refer to it as a lump of wire. Hanging it on the wall meant it could change form.

Final reflections

Returning to this writing near the end of my course, I reflected on how my making is a form of “being with,” as Tim Ingold describes in The Life of Lines. Making nests became a correspondence, an immersive process where understanding emerged through bodily engagement. Ingold’s concept of “coiling over” highlights the dynamic relationship between maker, material, and form. In this dialogue, my hands and the material seemed to co-lead the process, revealing an intuitive, meditative experience of time as a temporal flow.

This process deepened my practice, allowing me to take my work beyond the studio. Ingold (2013:6) notes, “These materials think in us as we think through them.” My nests embody this interplay, blending human and non-human connections. Each object became a vessel for emotional reflection, transforming cold, industrial wire into fragile, vulnerable forms. Through this journey, I discovered that my practice is not just about the visible outcomes but the layered, speculative processes—the fears, failures, and reflections that ground my work in experiences of creating and connecting to nature and myself. On a practical level, my costs incurred for material and labour (outsourced) are the same.

I do think this blog relates to my journey of how I started developing my body of work. The outcome of a coherent Body of Work has benefited from acquiring new skills and their application

List of Illustrations

Fig. 1 Stander, K. (2023) Drawing a nest [Video] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West, South Africa.

Fig. 2 Stander, K.(2024) Sociable Weaver Nest with Raffia [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West, Sout Africa.

Fig. 3 Stander, K. (2024) Nest in charcoal [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West, South Africa.

Fig. 4 Rademeyer, Sonya. (2022) Drawing performance [Photograph] At: https://www.sonya-rademeyer.com/performances (Accessed 03/03/2024).

Fig. 5 Davidson, D.S. (1935) Knottless knitting, table 2. [Photograph] In: American Anthropologist p 121.

Fig. 6 Hepler, A. (2016) Double Hung. [Photograph] At: Artist Instagram Post. (Accessed 04/05/2024.)

Fig. 7 Inger Weidema. (2024) Sharing looping technique. [Video] Whatsapp post on 02/02/2024.

Fig. 8 Stander, K. (2024) Wire Coiling Aid. [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West, South Africa.

Fig. 9 Stander, K. (2024) Getting help. [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West, South Africa.

Fig. 10 Stander, K. (2024) First wire loop work. [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West, South Africa.

Fig. 11 Stander, K. (2024) First wire loop work, different view. [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West, South Africa.

Fig. 12 Stander, K. (2024) Hotel Kalahari WIP. [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West, South Africa.

Fig. 13 Stander, K. (2024) Copper vessels. [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West, South Africa.

Fig. 14 Stander, K. (2024) Hotel Kalahari WIP. [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West, South Africa.

Bibliography

Davidson, Daniel, Sutherland. (1935) ‘Knotless knitting in America and Oceana’ In: American Anthropologist pp 116 – 134. At: https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1935.37.1.02a00110 (Accessed 11/02/2024).

Graf, Stefanie. (2022) ‘How Ruth Asawa made Fascinating Sculptures’. Read online In: The Collector, 05/09/2022. At: https://www.thecollector.com/how-ruth-asawa-made-fascinating-sculptures/ (Accessed on 03/02/2024).

Klein, John. (2019) ‘Ruth Asawa: Life’s Work’. Pulitzer Arts Foundation, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no1 (Spring 2019) Online. At: https://doi.org/10.24926/24926/24716839.1711. (Accessed 08/02/2024)

Ingold, Tim. (2013) Life of Lines. London: Routledge.

Interior Design. (17/9/2018) ‘The Wire Sculpture of Ruth Asawa‘ Online article read At: https://interiordesign.net/designwire/the-wire-sculpture-of-ruth-asawa/ (Accessed 08/02/2024).

Morris, F. (1989) Louise Bourgeois – I transform hate into love [Video talk] At: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/louise-bourgeois-2351/art-louise-bourgeois. (Accessed on 21/02/2024)

Synder, Robert. (1978) “Ruth Awawa: Of Forms and Growth.” Masters & Masterworks Productions, Inc. Filmed 1978. Video, 5:02. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T5eyKMEQizY.