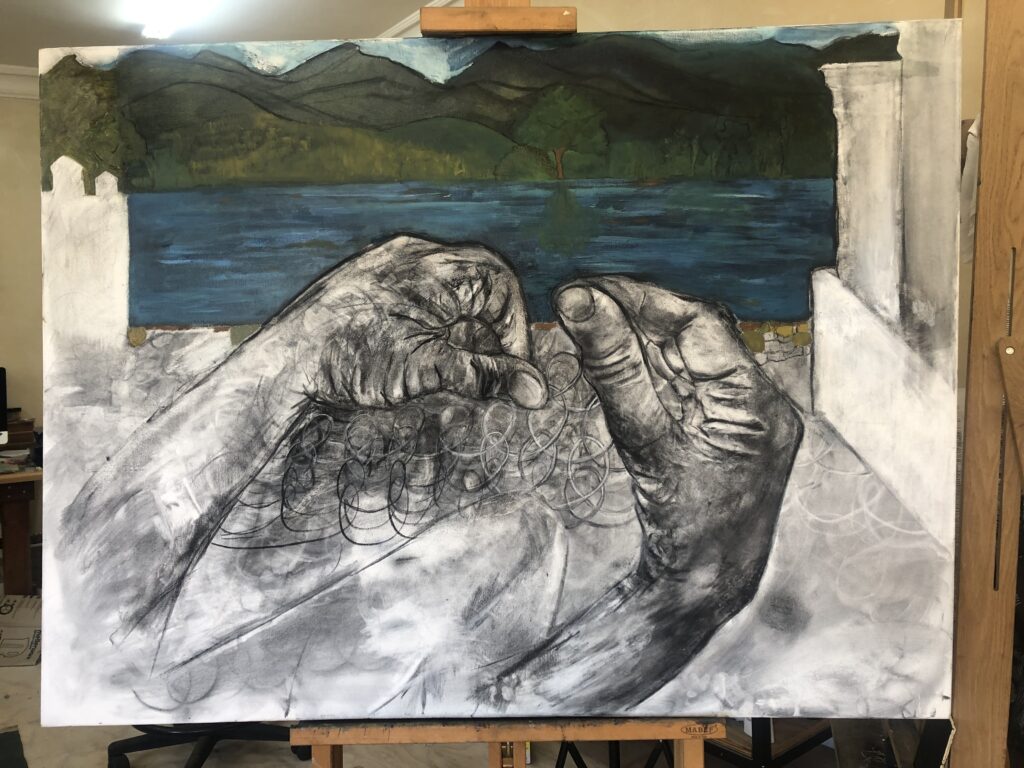

After the culmination of Hotel Kalahari, I revisited the physical venue and its layered experiences. I did not have to ‘break down’ the exhibition and decided to keep it in the space for the time going. The mixed-media drawing/painting I created below became a bridge between my initial concepts, the exhibited works, and the impact of the space itself. It feels like an extension of my studio—an opportunity to process, reinterpret, and deepen my understanding of what unfolded there.

Making a work after the exhibition became a way to process the fleeting interactions I observed during the event—the interplay of light, the movements of visitors, and the quiet stillness in between.

The above work is a reflection and a continuation of the exhibition’s narrative. It serves as a reminder that art does not end when the last viewer leaves the gallery. My tutor and I discussed whether one is ready to exhibit one’s work. Doing this after the exhibition, I learned that work evolves as we reflect on its place within a space, our lives, and the broader world. This process reinforces my belief that my studio practice and exhibitions are not separate entities but parts of a more significant, ongoing dialogue.

Regarding refining, adapting and resolving, I had to consider the art market: A curator visited me and looked at the body of work. We had a sensible conversation about the work and whether I should sell it as separate works. She suggested that I share it regularly on social media and find international online exhibitions to explore how the work is received. I should not feel urged to sell now. I should consider keeping them longer until at least the end of my studies but continue to do more work with the idea of selling. This way, I am ready to participate in group exhibitions or collaboration. Regarding pricing, we discussed that I should be careful not to sell at too low prices, but I still consider that the South African art market is not as profitable as the European or Western art Market. It could be worth my while to hang on to the work for a time.

I found an interesting comment from Tracy Emin: “I was terribly scared about my future. I sold some paintings, and made about £2,500, but nowhere near enough to pay back the bank. After I left, I was homeless, became pregnant and had a total breakdown. Eventually, I got a job working for Southwark council as a youth tutor and did a part-time philosophy course. I got my brain back into shape, paid back all my debts and started making art again.” The Guardian, 23/06/2015. Emin did her MA at the Royal College of Art MA, 1987-89.

In Part Three I wrote the following reflection around my strategy for the exhibition:

In “Kalahari Hotel 2024,” I intend to create a space that fosters reflection and connection. By drawing on the natural architecture of sociable weaver nests and the theoretical framework of heterotopias, I aim to provoke thought and dialogue about our societal structures and the spaces we inhabit. The work is also a homage to the remarkable nests of sociable weavers, inspired by their intricate architecture and scientific research into their multifaceted roles.

If viewers find new meanings or connections within this work, then it has achieved its purpose. Through this exhibition, I hope to create a junction where art, nature, and society intersect, offering a space for contemplation, connection, and perhaps a new understanding of the intricate webs that weave us together. This exhibition explores themes of home, safety, and adaptation through wire sculptures that echo the form and function of these natural marvels.

I decided to share this with some visitors and ask them to anonymously reply on their experience.

Regarding future opportunities, I have started dreaming of workshops in this space and considering residencies on the farm. In my future-facing practice, I will discuss this later in this part of the course.

In the meantime, I had the urge to work with wire, so I started a new shape and size, removed the nest from its hanging position, and placed it on the floor. I know I want to expand the work soon.

I had time to consider how, with my making, I am busy with a line, but also, within my making, I was thinking of what Tim Ingold wrote about ‘being with’ (The Life of Lines, chapter 17, Coiling over). I was being with a nest – a correspondence happened! I think the making process gave me a form of bodily experience. I would think this is what Ingold implies with ‘coiling over’. I agree the nest is not sentient, but I became immersed in sentience. I do believe there is an opportunity to go deeper into this idea. Two things I consider are how my hands guide me as I work and that, at times, the material seems to ‘lead’ the process. The other is how I experience time as a temporal flow – the experience is meditative and intuitive. I have no pattern to work on; I design as I go, start with an idea, and develop the form.

I am reminded of the word ‘curare’ around curating in Part Three and how I responded and want to revisit the following question in this part of the course:

“How might we curate, exhibit and make work from a personal perspective, that acknowledges our place, and agency within communities, global and local networks, and how might we respond with curare?”

Drawing on Dialogues:

Artists research and consider new materials or extend the current method

I have been researching the works of Anna Hepler recently. She works with ceramic, wood, metal, and paper, both hand-held and on a monumental scale. I learned that her work grows out of experience, so she lets each new piece be informed by the last. Hepler coordinates a series of mutations that turn a collage into a woodcut, a woodcut into a print, a carved woodblock into a sculpture, and a wooden sculpture into a clay form. She portrays folded, slumped, stacked or intertwined forms in which one material looks or behaves like another. Wood slats mimic hanging rope; woodblocks resemble animal hides; drypoint etchings simulate cloth scraps; ceramics are made of steel; and wire sculptures drape and flow like fabric. Hardwired presents recent work from Hepler’s exploration into the language of visual perception, its illusions, its grammar of depth, surface, and edge, and the impressions gathered when certainty is lost.

I started collecting cardboard to create a nest with rolled/folded cardboard.

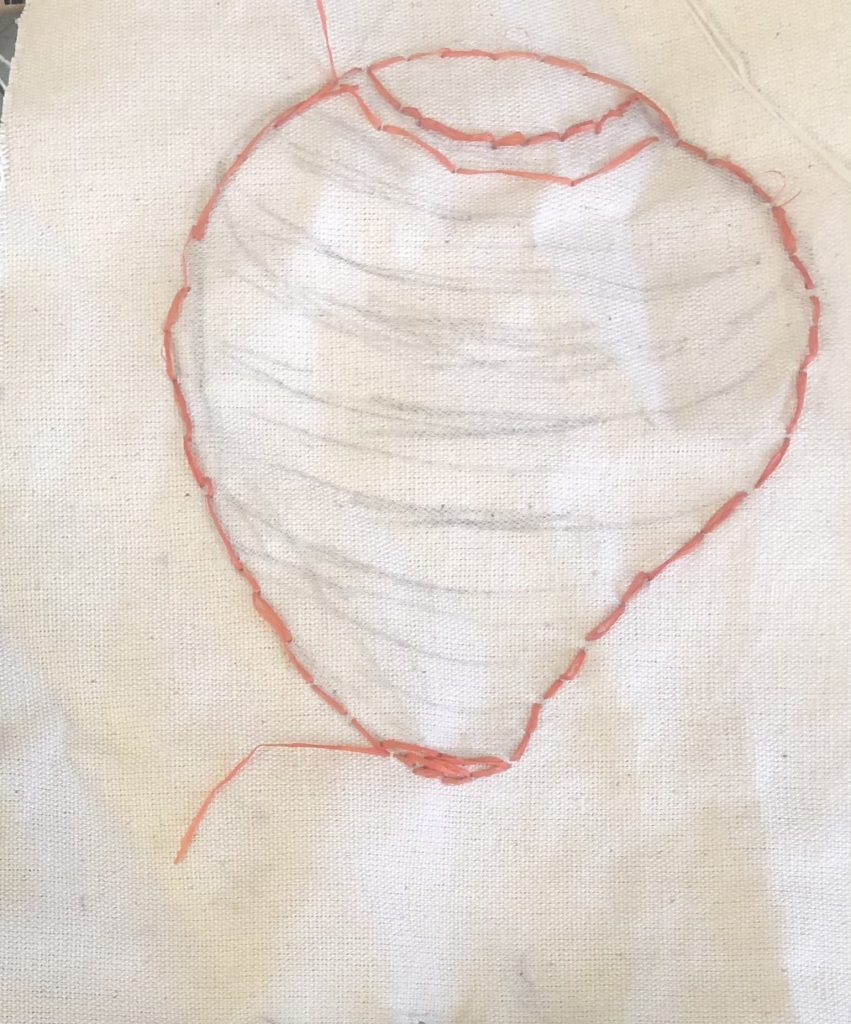

I have also started looking at using embroidery techniques to work with wire and other materials around nest making. A drawing I made earlier on canvas has been explored with stitches and materials.

Earlier in the course, I made an embroidery exploration of the containers I was weaving with raffia, and I think this can be further explored in my practice. I like the idea of bringing my hands working on materials into the work – making it more experimental and open to other materials. In the above work, I experimented with different gauges, textures, or types of wire to explore how they alter the dynamics of “coiling over.” There will be great opportunities to reflect on how each choice changes my relationship with the material and build an intimate knowledge of the ideas around a nest and materials I can use. I would say that by working with unconventional materials (e.g., wire, found objects, or textiles) I could see how different textures and resistances affect the correspondence.

The research task in this project is fascinating and ongoing.

I have never read about Michail Karikis, but immediately felt connected to his projects. I love how he works, finds inspiration and learns.

Mikhail Karikis is a sound and video artist who operates within a socially engaged practice, working with, or collaborating with groups of diverse people, often in poverty stricken areas of the UK, or internationally. Below he comments on his collaboration with a class of seven year olds at a London Primary School, on the film ‘No Ordinary Protest’ 2018.

“A lot of the props in the film were made in collaboration with the children…they were pushing the aesthetics in a direction that I would not have gone, had I not worked with them.”

Reflection

I see opportunities to expand my understanding of the nest as a symbol. This would imply that I will be able to deepen the emotional resonance of my work by embedding the voices and hands of others and keep pushing my creative instincts by embracing unexpected aesthetics.

Considering writing about “Being With the Nest” as an artist statement leads to the following:

In my artistic practice, making becomes a dialogue, a correspondence between myself, the material, and the form that emerges. This process resonates deeply with Tim Ingold’s concept of “being with,” as explored in The Life of Lines. Through the meditative act of coiling and shaping wire, I immerse myself in a dynamic interplay—not imposing a predetermined design but allowing the nest to reveal itself in its becoming.

Ingold’s notion of “being with” suggests an attentiveness to the material and the environment, a form of ‘bodily seeing’ that arises through hands-on engagement. This aligns with my intuitive approach, where the material seems to guide my hands as much as my hands guide the material. Each twist and curve of the wire holds a temporal flow, echoing the rhythms of natural growth and decay. The process is not linear but fluid, a dance between intention and surrender.

Time within this practice is experienced as a meditative continuum, where the past, present, and future converge in the making. With its inherent properties of tension and flexibility, the wire mirrors the precarious balance of life within a nest. The nests of sociable weavers, which inspire my work, are not static; they grow, shift, and sometimes collapse under their weight or the forces of nature. This precariousness is both a physical reality and a metaphor for the fragility and resilience of home, care, and connection.

Through this process, I aim to cultivate a sense of ‘being with’—not only with the material but with the ideas of home, loss, and community that nests embody. The nests I create are not replicas but abstractions, spaces where absence and presence intertwine. They invite viewers to engage not only with the forms but also with the shadows they cast, emphasizing the intangible dimensions of care and memory.

By embracing “being with,” my practice seeks to move beyond the dichotomy of maker and object, instead fostering a relational understanding of artmaking. It is a collaboration with the material, the site, and the viewer, a continuous unfolding of meaning that emerges in the space between.

Recently, I have begun to explore cardboard as a medium in my nest-making practice, inspired by the work of Anna Hepler. Her approach to allowing one material or form to inform the next resonates with my intuitive process. By rolling and folding cardboard, I aim to evoke sociable weaver nests’ tactile and structural qualities while inviting associations with shelter, fragility, and adaptation. Cardboard, an everyday material often discarded, mirrors the ephemerality and resilience inherent in the nests I study. This shift in material opens new pathways for collaboration and reflection, reinforcing that each iteration of my work is a continuation of a broader dialogue—with the material, the environment, and the concepts underpinning my practice.

London Primary School, in the film ‘No Ordinary Protest’ (2018).