SELF-MANAGED ART PRACTICE

Exercise 6: Part One follow-up 1 week – 4 week

Dedicate time to making and developing further from your Part One practice work. How can you extend and develop this? What strategies are working / not working so well? What do you need to keep making? Make notes and a simple proposal for the next week and the next 4 weeks.

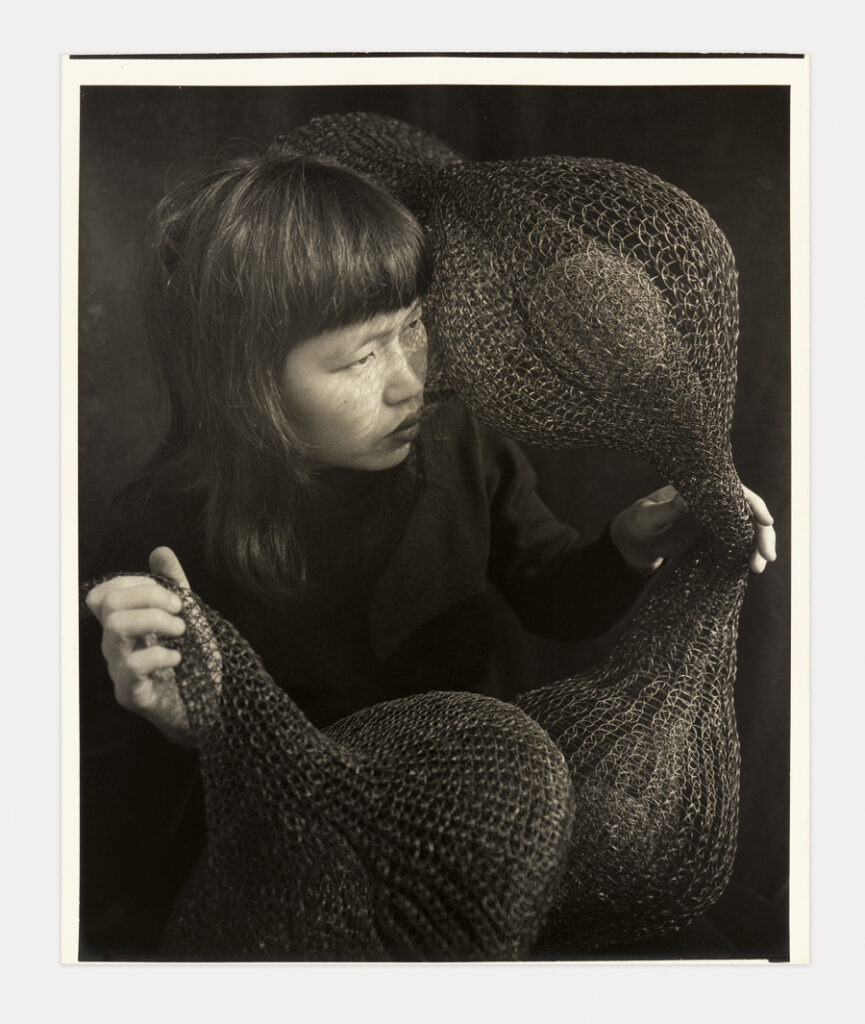

Notes to review: I looked at images and an article on an inaugural show, “Revolution in the Making, Abstract Sculpture by Women, 1947-2016,” by Curator Paul Schimmel, which was shown at the New Downtown Art Space Hauser Wirth & Schimmel during 2016. Here, almost 100 works were shown by ‘pioneering’ female artists, like Ruth Asawa, Claire Falkenstein, Louise Bourgeoise, etc. The following was taken to keep as contextual consideration for my own thoughts and writing about my making: “Can you tell us about the specific pieces you chose to display for your debut exhibition?

It’s a broad survey that really explores the revolution in the hands of women artists, in terms of new materials, new processes, new forms, breaking down of hierarchies not just having to do with identity politics, but the hierarchies of what is appropriate for artists to work with and express. So the earliest section — in many ways — the artists who came before the feminist revolution were both embracing aspects of modernism and doing so in ways that were unprecedented — the use of wire, stretched canvas, new materials that relate to primitive sculpture, basket weaving. Really, the profound change that took place in some ways, some artists got bigger, more monumental, more steel, heavier, and working with more fabricators or more things where they had to direct. This generation of artists really embraced the most intimate of expressions — realized as grandly as anything else — but done so with the sense of their own touch and feel. And what began with artists such as Louise Bourgeois, Ruth Asawa from San Francisco, and Claire Falkenstein, one of the great L.A. artists who has been overlooked, continue through a dialogue of artists like Jackie Winsor and [Magdalena] Abakanowicz. Their kind of monumental use of rope, fiber, and the primary forms and structures of circles and cubes. The loss of weight and gravity as seen in [Eva] Hesse, Gego, and Mira Schendel. The weaving of corners with Lygia Pape or the definition of a frame with Marisa Merz. The appetite to take over architecture with Cristina Iglesias and the beautiful concrete sculptures by Isa Genzken. And in the last section, the fourth gallery, you really have a new generation. Many merging here today: Lara [Schnitger], Kaari [Upson], others who live and work around here, Rachel Khedoori. They too have brought the legacy of all of these artists forward into an increasingly riotous use of color, a deeper sense of the relationship between the viewer and the object that is both installation and environmental, performative, and culminating in works like Phyllida Barlow. She will be representing Great Britain in Venice this coming summer with her immersive [installation], taking pom poms sort of “girl’s language” and turning it into a cathedral of pick up sticks and which you can wander in and through and among.” (https://www.pbssocal.org/shows/artbound/curator-paul-schimmel-on-the-new-downtown-art-space-hauser-wirth-schimmel) March 2016

Reflection :

I want to acknowledge the lineage of artists who have influenced my work, such as Ruth Asawa, who utilized wire to create intricate, transparent sculptures. Her work, like my own, balances the line between intimate craftsmanship and larger conceptual themes. I am also more aware of how the feminist revolution allowed for a broader acceptance of diverse materials and methods. This context helps to situate my work within a larger movement that values both the intimate and the monumental in art.

I need to explore the nest. It has become a symbolic place where I grieve and find a space to be alone but feel comfortable. It could be a symbolic place inside myself. I do not want to necessarily share all this with viewers and feel the nest can have different symbolic meaning to viewers.

The nest

I recently listened to a video conversation by Phyllida Barlow on her working with big sculptures and how she felt the viewer could come to view a familiar object which is turned upside down bringing a new opportunity. This reminds me of nests of birds – most of us have encountered them, but I can bring a surprise element into the work by making the viewer stop and figure out more about the nest. One can look into it, through it, move around it. I also ask myself in the making, at what point does the sculptural process take over the making – I am trying to ‘find’ a nest with my hands and the making. Phyllida Barlow referred to it as the ‘high point’. Why a nest, the form, the textures, the materials. I am also asking myself about the nest claiming space to create further conversation around, belonging and feeling comfortable and nurtured.

Wire objects:

My journey with wire objects begins long before the actual making. The meticulous preparation of materials often consumes more time than the creation itself. This essential groundwork introduces a certain stress to my process—the repetitive, laborious nature of preparation sometimes overshadows the meditative experience I seek. However, this duality is part of the artistry I embrace. I use a technique called ‘the art of e’ to craft forms and objects with wire. This method aligns with traditional basketry, and I researched it by looking at the wirework of Ruth Asawa. The ‘e-looping’ involves intricate loops and interweavings, creating a continuous form that draws from and contributes to the rich basketry tradition. Through studying the work of basket weavers, I found a sense of belonging in this age-old practice.

In the making process, the works become more than objects; they are three-dimensional line drawings—e-loops in space. The shadows they cast add a profound layer to their presence, resonating with my research on Ruth Asawa and Claire Falkenstein. In their works, negative space and transparency are not mere byproducts but vital material properties. Light filters through the wire loops, casting delicate, intricate patterns on the walls and floors. These shadows extend the sculpture beyond its physical boundaries, potentially engaging the viewer in a dynamic visual experience that changes with the light source. This concept profoundly influences my practice as I explore how light and shadow interplay to redefine the space around my creations. The looping technique further lends itself to creating fluid and organic forms, and the wire sculptures often appear weightless and airy due to their open structure. This lightness enhances their transparency and creates a sense of delicate balance and floating, contributing to their ethereal quality.

I cherish the making process itself the most. It is inherently speculative, driven by exploration rather than a predetermined outcome. This allows for a dynamic interaction with the wire, where I can manipulate the material during and after its creation. Each piece evolves organically, reflecting the fluidity and flexibility of the medium. Through this practice, I have discovered a deeper understanding of myself and my art. The process is a reflection and an exploration of my thoughts and emotions. I am excited about experimenting with new techniques and materials and continually evolving my practice. The journey with wire is ongoing, filled with endless possibilities and discoveries.

I find that wire emphasizes openness and fluidity rather than mass and solidity. The choice of wire as a medium challenges traditional perceptions of sculpture, often associated with mass and solidity. Asawa’s work uses wire’s inherent qualities to create robust and delicate solid yet transparent forms. I feel the final object plays with soft versus complex compared to a nest built by birds and the ‘nests/house/ we as humans build. Looking at the ‘archive-ability’, when viewing the works of Asawa, I am comfortable with continuous looping of the wire, which not only defines the form but also provides structural integrity to the objects. The fact that the wire is worked by hand, without complex tools, makes it a versatile and accessible material. I also value the simplicity of the technique and that it can form into organic shapes, which reminds me of nature or natural elements.

Thinking about emotional and conceptual resonance with the material, I could say that being such an open object due to the use of wire, the nest can symbolize vulnerability and interconnectedness and become inviting as a space for contemplation or reflection. I relate to P Barlow around her ideas on damage and repair – this is something we are constantly doing (adjusting to these changes) in personal/emotional relationships and seeing it in our environment and nature. She talks about ‘constantly shifting our lines of focus’ to know where the two meet – the reparation to the damage.

I contemplate my age and the fact that I started doing art and then continued to study Fine Art at a late age. I am writing this because SYP is nudging me to think and plan to become a practising artist and make plans for the future after this course. I am very aware of the process as I daily make, with a strong focus on the course and my own body of work — qualifying is only part of becoming who I am as an artist. The reality is to focus on this and work on it daily. My daily hours in my studio are essential, and I feel the course has been directing me here all along.

I want to contemplate and contextualise why I should consider shredding/destroying my work. At first, there was the idea of having so much work that I could call ‘failures’ or not for the market, and the idea to reuse paper as a weaving material was considered. (JohnSeed). What will be the learning or growth? Why would I do it? The other side is also, why do I think my art should not be destroyed – what value do I place on my work to keep it? I do not feel too attached to most of my work, which has become more so during my studies at OCA.

Not too long ago (05/10/2018), Banksy shredded (orchestrated) a painting just when it was auctioned. It was the last item on the list, no 67 for that evening’s auction. What happens here? Can it be seen as a protest act or a performance art spectacle? The shredding action transformed the work and challenged ideas of creation and destruction, again taking us to effectively redefine what constitutes “art” in the modern day. It seems the title change implies that the work changed status in the artist’s mind.

I also read that Banksy implied that the work should self-destruct completely, which did not happen at the Auction event. A quote from Picasso was at that stage posted on his Instagram account, it read: “The urge to destroy is also a creative urge”. (This post was also deleted) This was the first time ever that an artwork was created live during an auction.

A little research into the reaction: “Love Is In The Bin’ is,, therefore,, a work that exists in two states: its original form as conceived by Banksy and its transformed state post-half-shredding. The duality of this work only adds layers of complexity to its interpretation and, indeed, its value. The work is both finished and in flux; its value diminished by its partial destruction and made intensely more valuable thanks to its newfound historical significance.”

I think it important to link this ‘event’ to this other work, Morons (2006) which is based on the historic moment when, in 1987, Van Gogh’s Sunflowers achieved the price of £22,500,000 at a Christie’s auction and set the record price for the highest auction price paid for any work of art at that time. This moment marked the beginning of colossal changes in the art market, characterised by the emergence of the first ‘mega lot’ auctions. In Morons, the large canvas has written words in block capitals; the bold words read, ‘I CAN’T BELIEVE YOU MORONS ACTUALLY BUY THIS SHIT’. Again, Banksy mocks art collectors the world over who are ready to bid absurd sums of money to acquire artworks by himself or other famous artists. It also talks about the ‘elitism’ in the art world.

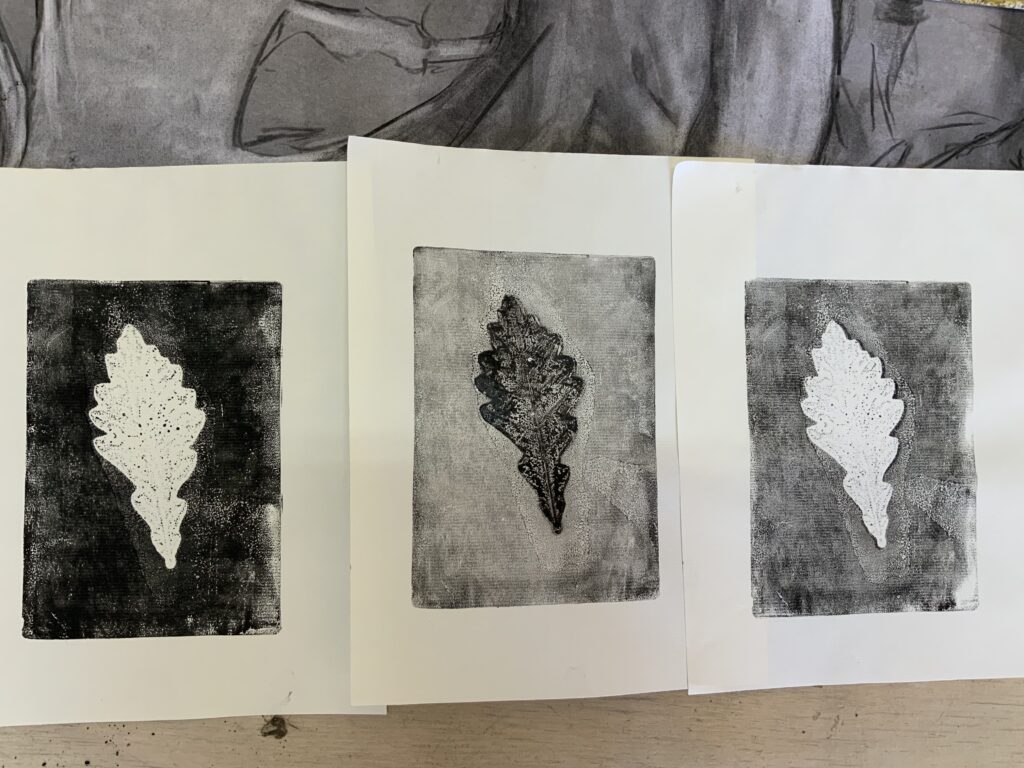

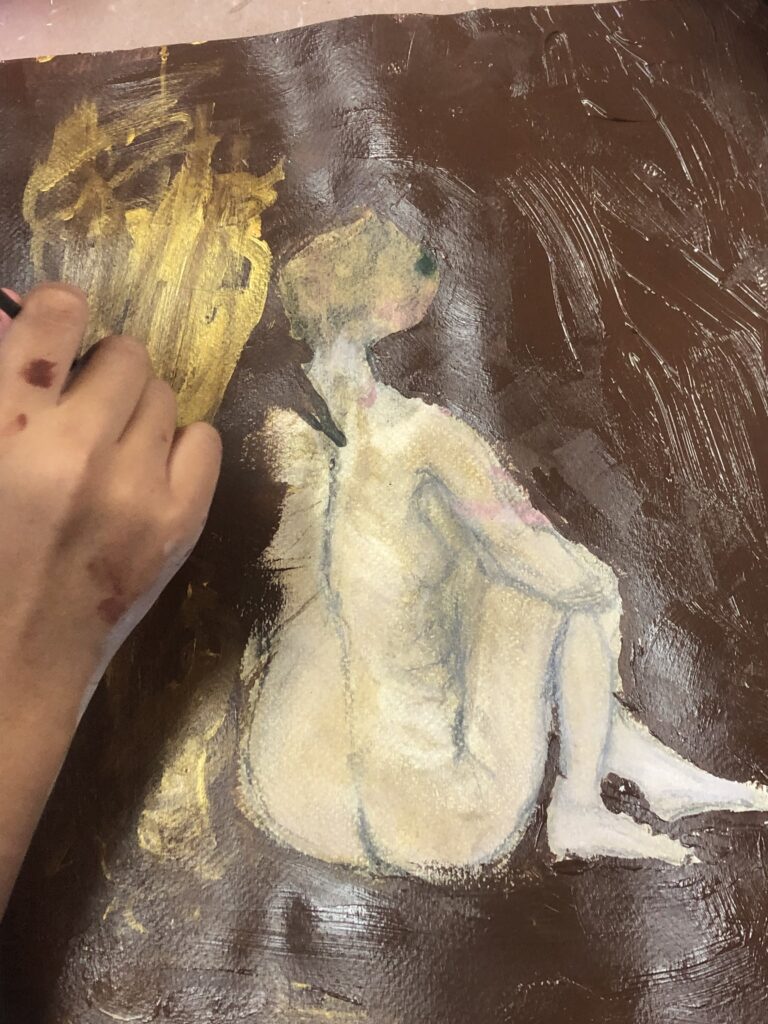

After the first attempt to ‘deconstruct’ my work, which was shared in the first part of this learning log, I decided to take some work to the art class with young kids that I help facilitate here in our community. At first, I did not want to disclose that the work was mine and thought to suggest to the kids to use the work as ‘ground’ for their painting/drawing. I shared a little about the blankness of a canvas and how it can be intimidating when one starts to work, and then showed my work and suggested they use it. I wanted to understand their experience and reaction to this ‘experiment’. Our work in the art class was around Breath, Breeze and Winged Things for an upcoming exhibition. The class was also dealing with the sudden death of a facilitator, and I suggested they use this as an opportunity to think about the cycle of life, what is precious and what we can let go of. We used straws to blow the ink around the surface, making paintings and monoprints with leaves. Interestingly, they did not want to work on my monoprints. I would say making their own was more ‘attractive’. I think it was a curiosity to learn something new

It became clear that most of the kids were almost astounded that I could do this, and when they started to work, they did not want to ‘destroy’ my part but only tried to bring in their work alongside what already was on the surface. We discussed this as a possible idea around ‘collaboration’, but I pushed them to express themselves by using ‘my work’ as inspiration to change the work and leave a trace of themselves. The choice was open to have a clean paper to work on or to choose one of my ‘works’.

Creation and interconnectedness are core themes in my nest-making, and I want to explore these concepts more. I can share personal experiences and explore my ideas. By creating oversized nests that can fit a human, I seek to contemplate our human need for connectedness. This connectedness is a safe space and can be within families, friends, nature, or art. In this way, weaving (e.g., looping and random weaving techniques) became a literal and figurative process that connected me with my materials, thoughts and viewers.

It is essential to consider the difference between scale and size.

Reflecting on my intentions

Reflecting on Banksy’s “Love Is In The Bin” gave me a valuable lens through which to consider my artistic practice. By examining themes of destruction and creation, value, duality, and historical significance, I can gain deeper insights into the complexities and potentials of my work. I must embrace these reflections to enhance my art’s conceptual depth and narrative richness, making it both a finished piece and an ongoing process.

The above reflection asked me to consider how I balance the idea of my artwork being a finished piece versus a part of an ongoing process of creation and destruction. I now felt more comfortable with my WHY. I can also add that this experience motivated me to add to my body of work a work that will be presented at the upcoming Solo Studios exhibition (August 2024) where the viewers can build or deconstruct my work. The process will be documented. I started making a list of ‘reusable’ materials which could be used at the exhibition.

How big will the nest go? I do not know. Will time show? I once read this quote as shared by Phylida Barlow: ” In Duchamp’s fantastic lecture The Creative Act [1957], he talks about the process of transmutation, about things in the world becoming something that has never existed before, like sugar cane being refined to become molasses. I find that very non-judgmental. Unfortunately, Duchamp is used academically as a prop, where verbal language is prioritised. In the end, that is what I am trying to escape.” On the Royal Acadamy website (https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/magazine-phyllida-barlow-conversation-harrison-birtwistle

Considering this, I believe art should not be based on time spent or labour intensity; art values the inherent creative process and the outcome as something novel and original. The implication for my work: Whether a nest takes hours or days to create, it should focus on the transformative journey of creation and the emotional and philosophical insights it brings forth. I also think this work will only have a ‘limited’ time frame; it will fill some space, but there will be no permanence. We will take it away and even change it. I can consider making drawings of it to have something that lasts longer. I could also see if it could ‘deconstruct’ if the wire is exposed to the weather conditions and erode.

More wisdom was found from P Barlow when I searched damage and repair and the personal and how it is part of her process of making, she talks about being interested in the ‘cycle’ of damage and repair and working on that edge: “Coming back to damage and repair: We also see this in the urban environment. Things we have been very familiar with are almost overnight wiped away by demolition, and then the new glass building goes up. And I think psychologically, we are constantly adjusting to how we relate to global disasters and our own more intimate disasters within our families. We must constantly shift our focus lines to see where the two meet: the reparation for the damage. So, including this in my making process is a kind of subject. It’s a crucial part of being alive.” (https://www.dreamideamachine.com/?p=83017 the video https://vimeo.com/757513110). This discussion also touches on the ‘permanence’ of artwork. I would agree with Barlow that I am not interested in permanence.

I wrote the following around my ideas of impermanence as it is a place where I find myself in the process after the above learning and reflection:

In my nest-making practice, I also explore the concept of impermanence using materials traditionally associated with durability, such as copper and steel wire. This juxtaposition creates a rich dialogue between the transient and the permanent, inviting viewers to reflect on the ephemeral nature of life.

Nests in nature are mostly built as temporary shelters, serving their purpose before being abandoned. Similarly, my wire nests symbolize the fleeting moments and experiences that shape our lives. Though made from materials that suggest longevity, these nests are intended to evoke the beauty of impermanence. Over time, the wire may tarnish and change, mirroring the natural processes of ageing and transformation. This exploration is deeply personal, reflecting my journey through loss and the acceptance of life’s transience. The nests become metaphors for the temporary homes we build, the care we provide, and the inevitable process of letting go.

By embracing impermanence in my work, I aim to create art that resonates with the universal human experience of change and transition. The wire nests remind me that even the strongest structures serve a temporary purpose, and there is profound beauty and meaning in their eventual transformation.

I was also thinking of further investigating the concept of care in my work after reading an article on hyperallergic.com: “In considering the term “care” as a provocation in work by contemporary artists, I am drawn to feminist ethicist and psychologist Carol Gilligan’s concept of it. Gilligan describes care as “an ethic grounded in voice and relationships, in the importance of everyone having a voice, being listened to carefully (in their own right and on their own terms) and heard with respect.” Such a compelling proposition is present in artistic practices that critically engage with and accessibly activate this concept of care. In particular, the statement in their own right and on their own terms resonates with these artists, who are charged by their experiences to activate responsibility, access, and inclusion in their creative practices.” (article by Lisa Slominski, published on March 9, 2023)

Care and interconnection are strongly related in my work. I suggest we see it or look at it as a holding space as well as a feeling of being held and grounded. Care is not only a feeling (to feel being cared for); it is action, process, and practice, and it makes or has an impact. Care is relational and personal and becomes an ongoing practice.

Bibliography

Argun, Erin Atlanta, https://www.myartbroker.com/artist-banksy/articles/banksy-shred-five-years-in-the-market

Slominski, Lisa,

Research task: Ten practitioners

Throughout your studies you’ll have discovered a large number of practitioners working in a variety of ways and your knowledge of your chosen subject will be as diverse as you are individual. Whether you already have a clear idea about the way you want to work or whether you still have questions you’re looking to answer, you will probably have a sense of how your work fits in context with the practitioners you relate to.

Make a list of 10 practitioners who you feel can support your ideas and practice. They may be artists you admire and who work in media or with subject matter in a similar way to you. However, they may also be artists who make work that challenges your ideas and that you use as a foil or sounding board against which to analyse your work. They may broadly work in similar ways to you, overlap with some of your ideas, approaches and processes, or have opposing practices. Once your list of artists is complete, ask the following questions of the practices of each one.

Ruth Asawa: I have to include Asawa into my list as her practice is closely linked to my wire objects and I have done a lot of research into her practice.

Sopheap Pich (Cambodian artist working with rattan and wire)

Ulrikk duFosse (New York wire artist—doing looped work as Ruth Asawa): I found it interesting that he uses the same white floor displays to show his work, as one sees with Ruth Asawa’s work. This made me consider researching how I could use this, as the benefit is great light and play with transparency and shadows when exhibiting the works. His practice is described as a form of knitting. The long hours it takes to make are also acknowledged.

Andy Goldsworthy

Elishia Jackson (Australian Fibre artist)

Tininha Silva

Jennifer Quan

Petrit Halilaj

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV

Antony Gormley ( British – inspirational large drawings – very indexical, of the moment)

Anna Mendieta (Silueta Series)

I decided to focus only on Ruth Asawa for this part of the question

What is the subject matter of your practitioner’s work?

Ruth Asawa’s subject matter primarily revolves around nature, organic forms, and the interplay between space and material. Her wire sculptures, often reminiscent of natural forms such as flowers, roots, and sea creatures, reflect her deep appreciation for the natural world. Her intricate and delicate patterns highlight the beauty of simplicity and repetition.

What are they responding to in their work?

Cultural Heritage and Personal History: Asawa’s Japanese-American background and experiences during World War II, including her internment in a Japanese-American internment camp, deeply influenced her artistic vision. Her work often embodies themes of resilience and beauty emerging from adversity.

Creative Research: Asawa was influenced by her studies at Black Mountain College, where she was exposed to avant-garde artists and educators like Josef Albers. This environment encouraged experimentation and pushed the boundaries of traditional artistic techniques.

Social Concerns and Education: Asawa was a strong advocate for arts education. Her work and her efforts to integrate art into public education reflect her belief in the transformative power of art. Her sculptures were not just aesthetic objects but also tools for engaging the community and fostering creativity in children.

Nature and Organic Forms: Her immersion in nature and organic forms was both a personal and artistic response to the world around her. She found inspiration in the natural environment, translating its complexity and beauty into her wire sculptures.

What makes their ideas contemporary and critical?

- Innovative Use of Materials: Asawa’s choice of wire as a primary medium was innovative and ahead of its time. She transformed an industrial material into delicate, intricate artworks that challenged traditional notions of sculpture.

- Intersection of Art and Craft: By blurring the lines between art and craft, Asawa’s work questions and expands the boundaries of fine art. This approach is particularly relevant in contemporary discussions about the value of different artistic practices.

- Community Engagement: Her commitment to arts education and community involvement resonates with contemporary practices that emphasize social engagement and the democratization of art. Her legacy in public art education inspires new generations of artists and educators.

- Minimalism and Abstraction: Asawa’s work is often seen as a precursor to minimalism and contemporary abstraction. Her focus on form, repetition, and space aligns with crucial principles in these movements, making her work relevant in today’s art discourse.

- Resilience and Identity: Asawa’s work explores resilience, identity, and cultural heritage, which speaks to current social and political conversations about race, identity, and the immigrant experience.

How could you start a conversation with them?

I wrote a little script:

“Ms. Asawa, I am deeply moved by your incredible wire sculptures and dedication to arts education. Your work has inspired me and countless others who see the beauty and complexity of your simple materials. Thank you for your contributions to the art world and for being such an inspiring figure.

Tell me how your artistic journey began. What initially drew you to working with wire as your primary medium? How do you refer to your making? Many people ask me if I call it weaving, crocheting or knitting.

Your sculptures often evoke natural forms and organic patterns. What aspects of nature inspire you the most, and how do you translate these inspirations into your intricate wire works?

You have been a passionate advocate for arts education and community involvement. In your view, what role does art play in shaping and enriching our communities, especially for young people?

Your work has left a lasting impact on the art world and public art education. How do you see your legacy, and what do you hope future generations take away from your work and your approach to art?

Many contemporary artists explore themes of identity, resilience, and cultural heritage, much like you have in your work. How do your experiences and artistic expressions resonate with today’s social and cultural conversations?

Thank you so much for sharing your insights with me, Ms. Asawa. Your thoughts on art, community, and the creative process are incredibly inspiring. I am eager to apply these lessons to my practice and continue exploring the themes that resonate deeply with me.”

To conclude this research, draw out three or four key points from your answers to the above questions that offer useful knowledge to keep at the forefront of your making.

The time it takes to make.

Gestural work, which is in the present moment.

Look at the shapes and volumes – as if suspended in the air.

DuFosse works with interior designers as well as art dealers. – balance between craft and art is important, could be an issue to address.