Considering risk and looking at the reading point suggested in this project.

Exercise 2.1. UNDERSTANDING RISK

What factors stop you from taking risks within your work and how do you stop these getting in the way?

Ideas that all work should be as best as possible and almost ‘hide’ the flaws. Time is also a consideration – it takes time to explore and learn. I think I sometimes feel I have to have something to show and force me to work to what I think is ‘acceptable’ to the viewer, not necessary what I would like to pursue.

How necessary do you feel taking risks and embracing chance is to your work’s development?

I believe it is important to push boundaries of making and to take time to observe how I make. By doing this I realized that I am not scared to experiment or feel too precious about developing work, or even have to discard it. I think making more personal work also brought me to a place of unexpectedness – new thoughts and some painful experiences are embodied into my making – what control do I have over this? I recently looked at an image of the studio of Louise Bourgeois in Brooklyn;, when she was working on her Cells series, one gets the feeling of how her work completely takes over the studio, in a more dramatic/massive size of the work way, than say the work of Kurt Schwitters (learned about his work in UVC2). It is as if her work can consume the space it is in. I think in that way one’s studio becomes the most private space to use to ‘overcome’ / come to grips/be honest, about how one is living live, much more reality.

I took a feather drawing and added mushroom spore prints onto it. I shared it on IG, but then in a impulsive action, I made two small drawings on it. I do not feel comfortable sharing this, but I think I would like to leave it and contemplate the use of figures in the work. I do believe it is a way of connecting with the other, more-than-human in the work. I also think passion and ideas drive one to experiment with less fear. I believe that when I work around research and reflection I find this space to open up my own intentions. I am more honest.

Could you describe an occasion when taking a risk with your work proved to be a really positive move?

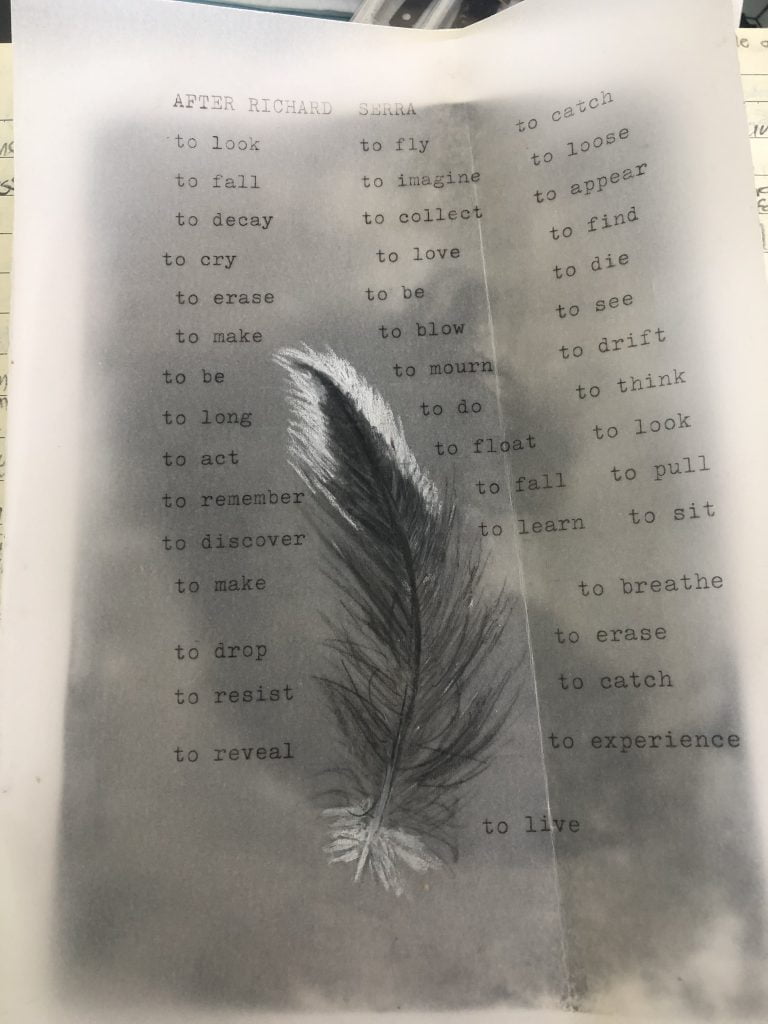

I recently started working with feathers as a daily meditative practice and to deal with loss and grief. I became more interested in the materiality of feathers and how I could inform myself about them. This led to making a process type of list which reminds me of working with feathers and the inspiration was taken from Richard Serra. I was thinking: to fall, to catch, to float, to drift, to fly, to grieve, to experience, to drop, to learn, to think, to imagine, to cry… the list became a way to look at the nature of feathers and how they interact with my own emotional experience and observation of self during this period.

It made me consider making installation work. It was completely unfamiliar to think how to hang the work and create a shape/form for it to become a 3d work., all made with feathers as the material.

Could you describe a moment where you were able to use failure as a positive tool within your practice?

Early on in my attempts at making a vessel, the vessel collapsed. I made a vessel with cellulose material (building material) which I used for printing, and built it around a balloon that I placed outside to dry – the balloon burst by the time I checked on it, and the vessel had collapsed partly, as it was not dry enough. and not being able to hold up its weight. I joined a fellow student for a making morning and we discussed different fabrics that could be softer to use. I have not given up and take the lessons learned with me. The vessel eventually dried.

I have composite copper leaf sheets and plan to ‘mend’ my vessel after it dried.

Exercise 2.2. BEYOND “failure”

Using Charlie Chaplin and Silent movie in the images makes me think about how he used humor to make his audience laugh, but also inwardly, challenge their own ideas about shame/failure/societal rules

I think the fear of failure should not hold one back, but it takes a lot of courage to come back after a failure and try again. I think one has to consider your emotional feelings of self-worth during such a process when you feel the work did not turn out as intended and you deal with it as being unsuccessful or just plain ruined. I tend to think about what if I did….. or I should have done ….. It makes me think about being process focused – the fact that the end result is not what should be important, because there is so much learning to gain from the process.

I actually think that failure is necessary and part of any creative effort. My concerns are mostly with my own inner critique when I start out to work – how to keep it under control to let creativity flow.

Kintsugi, or gold splicing, is a physical way to deal with resilience. Instead of discarding marred vessels, practitioners of the art repair broken items with a golden adhesive that enhances the break lines, making the piece unique. They call attention to time and the wearing down of objects due to use. This practice—also known as kintsukuroi (金繕い ), which literally means gold mending—emphasizes the beauty and utility of breaks and imperfections. It clearly turns a problem into a plus.

I found the following post by artist, Magdalena Abakanowicz:

Nassar, Hammad, Whitechapel catalogue

Exercise 3.1: STAGING CHANCE

STAGE ONE

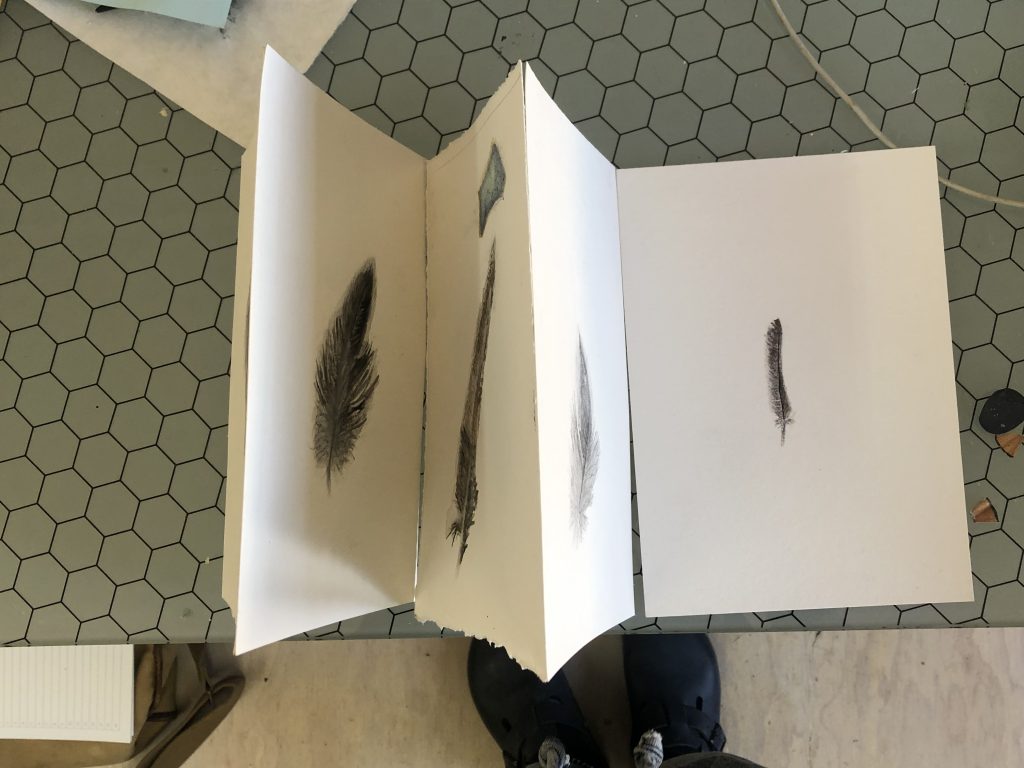

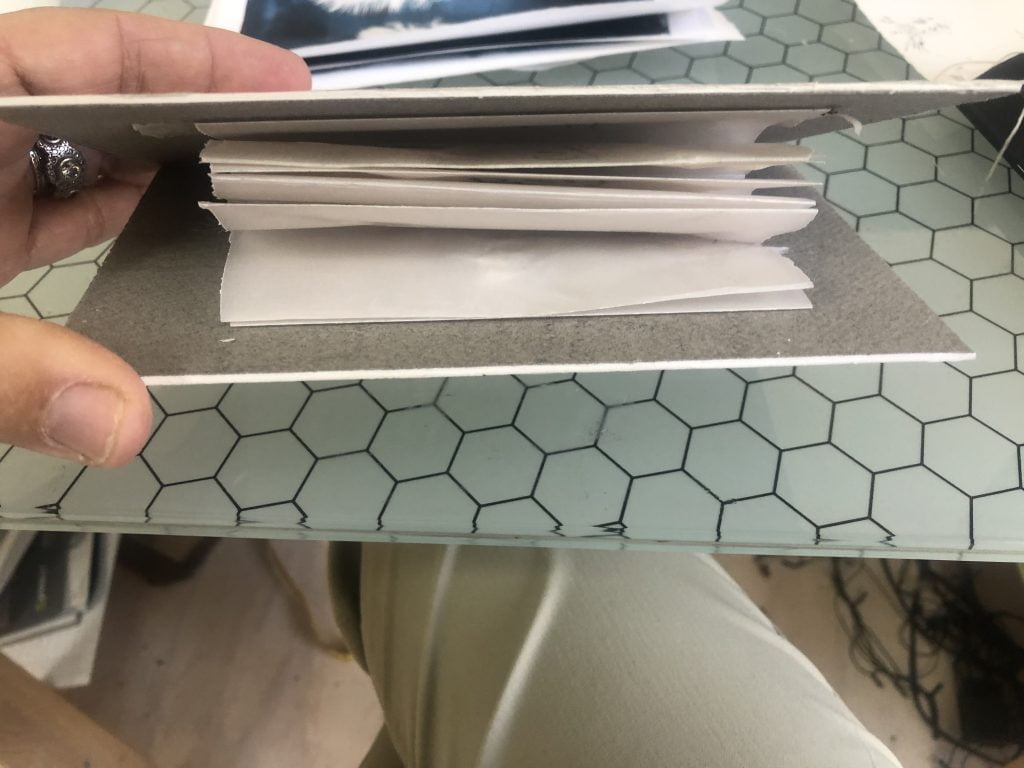

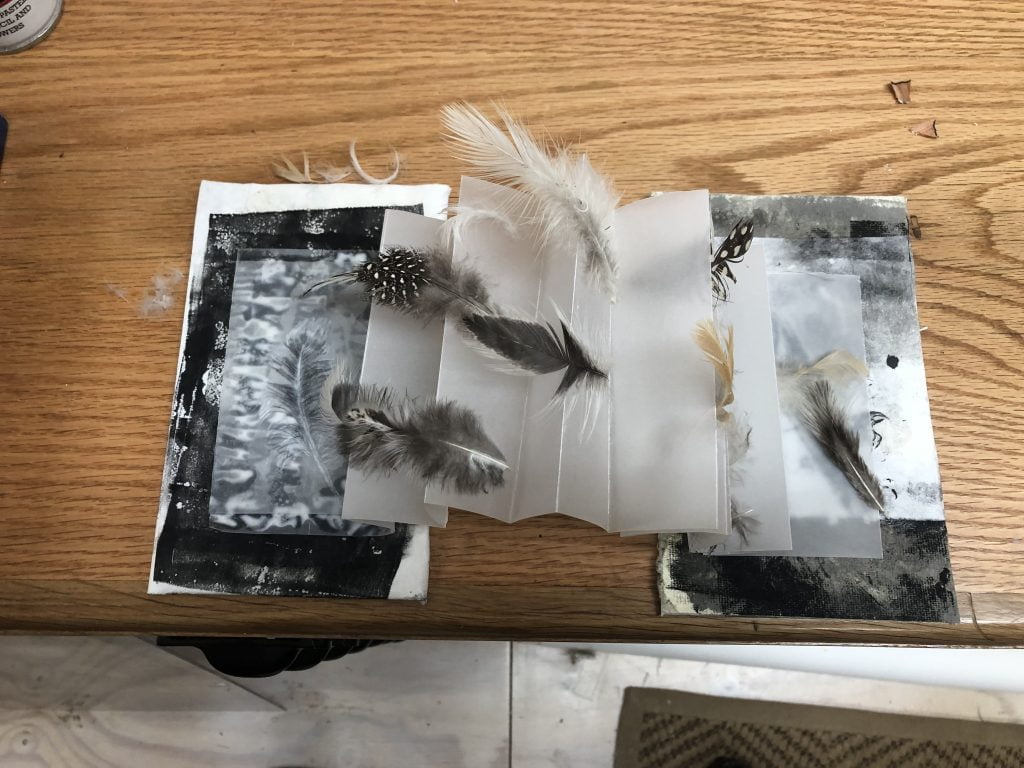

I have recently tried to make vessels and artist books with feathers. I worked with techniques of paper mache and folding paper, something I have never done as part of my making. During the making process prints I made were used to make new work, namely the covers of the artist’s books.

For the vessels, I used a critique group (students from OCA EU group) to suggest ideas for making and exploring feathers. I spent a few hours with a textile student to talk about making, sharing our making, and influencing each other’s work – this was done over a Zoom meeting and some Whats app sharing of images and talking about the process. The first vessel was formed over a balloon and made with paper and tea bags, and the second vessel was placed inside a bowl, using only white glue and feathers.

I explored hanging the vessels and finding different use of feathers as another layer of the vessel as well as ‘feet’ /base, by drilling holes into it and adding feathers as feet or decoration. I considered it with a painting, by hanging it in front of it, like a mobile. I eventually came to the conclusion that the vessels are ‘strong’ enough to stand on their own, without being supported by other artwork – to me, it talks about a holding space for emotions and thoughts.

The vessels made me think of using only feathers and placing them inside perspex. I first made a ‘drawing’ with the feathers and would like to explore this. I am not comfortable gluing the feathers together as I have seen with the work of KateMccGwire. I see the feathers as being free-flowing as part of their intrinsic quality, which I am not sure I want to alter at this stage of my development of BOW. I do not have an objection to placing them ‘behind’ glass or perspex, or resin.

In the image below, I placed the arrangement of feathers inside a perspex A4 menu holder to see if it could stand as a piece. I do not think this is the correct ‘holder’ and will work on finding a more suitable vessel.

(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mUMhry8lUoI)

Use of feathers for the art books was mainly through chance as I was looking at my daily drawings and thinking about how to present them in an upcoming art exhibition in our town. I was folding paper and looking at options to show these works. The first attempt was a small folded ‘book’ with cut-outs of feathers after I could not figure out a way to ‘bind’ scraps of paper into a foldable book. The loose small drawings were eventually framed.

I then worked with printed daily drawings to make a proper cover and made 3 artists books, I called the Book of Feather I, II, and III. In one of them, I wrote a poem about feathers.

STAGE TWO

Whilst working with feathers I go back to the story (myth) about Daedalus and Icarus. After his father made their wings to escape prison and warned his son, Icarus to fly not too close to the sun or too low, Icarus became ‘overconfident’ and flew too close to the sun. Their wings were attached with wax, so his wax melted, the feathers dropped and he tumbled to earth and drowned in the sea. I think in art making one also has to fly between extremes, you have to have ambition, but also not become apathetic about your making. Below is an image of a work in oil by Carravagio, Dadalus and Icarus.

Earlier in my studies I attended a session with a music department tutor and we worked in groups with music as

I decided to alter the work. I was influenced by an earlier session with dr Carla Rees, OCA Music Programme Leader and Tutor where we looked at music and art as creative spaces to create in. Ideas about time, memory, repetition, patterns, and improvisation were discussed. One of the good experiences was that we were making art whilst reacting to visual and sound/music responses. A copy of the recording of these sessions is still available in a G drive folder, and I remember our group worked with music called Daedalus. By now I have been reading the myth/story about Daedalus and Icarus.

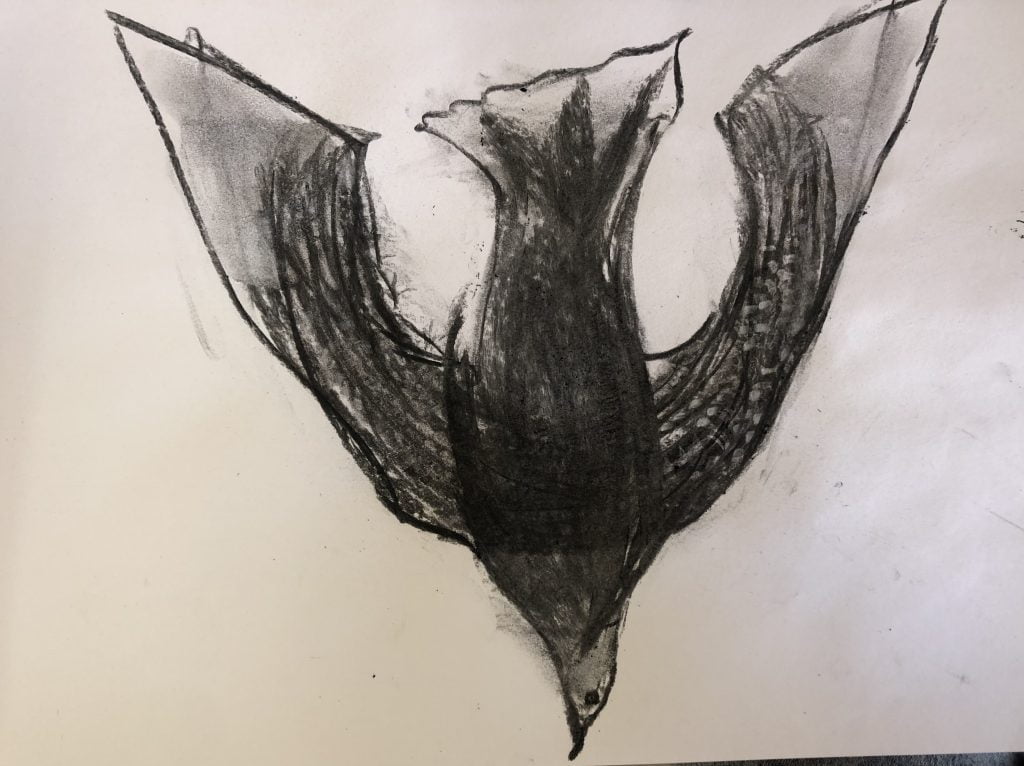

My making was inspired by the story of the Greek mythology of Daedalus and Icarus. I started with a charcoal drawing and intuitively started drawing into the drawing until it became a bird diving downwards. I photographed the process of drawing as I continued making changes and then add this to my iMovie app. I listened to music whilst drawing and decided to use this as the accompanying sound. The music was taken from a lyric video made by Christopher Tin and features the Royal Opera Chorus, after a YouTube search on the story. The ‘Daedalus and Icarus’ is sung by tenor Pene Pati with the backing of the Royal Opera Chorus. By now I was thinking that I could develop the work with more drawings and, or paintings. I can confirm that listening to music whilst drawing did change my way of working, and there is much more of this composer’s music that I enjoy. I felt comfortable to moving into a ‘new territory’ and was not concerned if the outcome is not great. My concern was to go with the material and my own feelings to create. If I do not try, I will not learn. I added other images, previous work, like a photo image, and considered how to blow onto the feathers. i think this creates some chaos as it cannot be controlled. The process showed me that I can develop more work, it was inspiring and stayed mindful. I will need to look at more upskilling my video editing if I continue with video/audio presentation. For now, I plan to make a bowl with the feathers by using resin and look at using a perspex box with two small holes drilled (with small latex airball pumps) where viewers can blow into the vacuum and create movement. This will be an interaction where ‘the work’ will never be the same, and create an interactive experience with making as well as my material.

With regard to copyright, I wrote to the composer and requested permission. The video footage is 33 sec long. Feedback from his team kindly remarked that he would be honored that I chose the composition, but, “….Technically a license is required from the entity that owns the master recording which in this case is Decca/Universal.” (E mail reply received from Meg Davies, Music Productions for Christopher Tin.) I feel that I have only used a short snippet of the work and will not follow through with the copyright issue. I will take cues from my tutors.

I share the video on my learning log for the viewing of my tutors only

I would also consider rules when I explore work with chance.

However, feathers are bio-resources with high protein content. They consist of about 91%

keratin protein, a hard, fibrous protein also found in hair, skin, hooves, and nails, a good source

of a natural adhesive. Feathers might be the most abundant keratinous material in nature (Khosa

and Ullah, 2013), that are yet to be adequately utilized in the wood adhesive formulation. Colored feathers: Although blue, green and color-shifting iridescent feathers—as seen in peacocks and hummingbirds—share a specific structure consisting of a layer of spongy keratin and another of pigment-carrying melanosomes, Science News’ Carolyn Gramling points out that these so-called structural colors can be further broken down into iridescent and non-iridescent groups.

Keratin doesn’t fossilize well, but melanosomes often do. In fact, National Geographic’s Greshko writes, fossilized pigment sacs have already been recovered from an array of prehistoric creatures, including non-avian dinosaurs, marine reptiles and various bird species.

By drawing on this abundant data source, Babarović and his colleagues set out to discover whether a specific melanosome shape could be associated with non-iridescent blue. Their findings, potentially indicative of an evolutionary link between gray and blue, make it more difficult to determine whether an ancient specimen was one color versus the other, actually lowering the accuracy of previous predictive models of fossil color from 82 percent to 61.9 percent.

Molting

Microraptor’s shorter feathers appear in just a small patch on one of the dinosaur’s four wings — suggesting that the dinosaur molted sequentially, too, bird ecologist Yosef Kiat at the University of Haifa in Israel and colleagues report.

All modern, adult birds molt at least once a year to replace old, damaged feathers, or to exchange their bright summer colors for drab winter camouflage. Genetic reconstructions of bird lineages have previously suggested that sequential molting has existed in birds for at least 70 million years, and was a trait of the common ancestor of all modern birds. But this is the first fossil evidence of a nonbird dinosaur exhibiting this behavior. Furthermore, the researchers say, the find would push back the estimated origins of sequential molting by 50 million years or so.

Feathers appeared in dinosaurs millions of years before the first birds and initially had nothing to do with flight. In fact, full-fledged contour feathers have been found on dinosaur species that did not fly.

“The original feathers were simple filaments or down feathers, and probably used for body insulation, camouflage, but also display,” Foth said.

“This probably was also true for the first contour feathers. However, once contour feathers were evolved, they could be easily recruited for aerodynamic functions,” Foth added.

The study was published in the journal Nature.