EXERCISE 2. BRINGING THINGS TOGETHER. FIRST FULL DRAFT

Contextual Study (5000 word count, currently on 4790) and considering style and tone

Exploring how theories around interconnectedness (entanglement?) with nature can open new ideas for making in a contemporary art practice

I will present this as a Word document for my tutor to annotate. I am unhappy with the conclusive part and need clarity if I add a literature study. I have looked at using citations, a bibliography and a list of illustrations according to the Handbook for Harvard Referencing. I will also add my Glossary of Terms(currently a separate blog entry on this site ) definitions for words used in the writing. I need clarity if I use footnotes instead of the Glossary of Terms. I also think my images should be a specific size, and using the Word application, I need to clarify dimensions. Another thought is to add images as a separate attachment to the writing and place smaller images in the writing part?

Use it as word – save it as a PDF.

The purposes of an Academic essay – do not loose structure and clarity.

Background and introduction to entangled thinking through my body of work

My writing is based on the perspective that human life is entangled in many relationships, including

non-human ones. I will explore how theories around interconnectedness (entanglement) can open new ideas for making in contemporary art practice. My making practice will be considered alongside. This perspective sees the human involved in a multiplicity of relationships with human and non-human others and refuses human exceptionalism.

I owe much to the research of Posthumanism, Feminist Phenomenology and Eco Feminism, where I mainly focussed on work done by Donna Haraway, Ursula le Guin and Maria Puig de la Bellacasa. I want to introduce as background to my making that my choice of materials, like feathers, fungi and nests, are not just passive instruments or containers for social meaning or symbols; I see a fluidity and relation between all things, human and non-human.

For the sake of my question about interconnectedness, non-human ones include other creatures (plants and animals) and the things (objects) of the world. I prefer to think of objects, things, animals, plants, and nature as part of my human experience. To use the words of Haraway, they are ‘companions’ in this world. I would say that this grounds my work fundamentally away from any ontology of anthropocentric or humanist philosophy. I cannot place agency strictly in the human realm and want to move away from a humanist or anthropocentric ontology. I prefer focusing on fluidity and the relation between all things, human and non-human.

Finding my way into – imagining a world where I am the woman with the basket, and how I fill it is a question that matters. (Val Kimerer p 177)

I wanted to apply a structure around the themes of connectedness to discuss other artists who interweave within this theme and show how this influenced my making. To compare, I will look at theorists such as Dona Haraway, Puig de la Bellacasa, and Le Guin. Haraway (When Species Meet, 2008) emphasises the intertwining of the natural and cultural. She goes as far as to discuss the concept of “nature cultures”, organic and inorganic, material and immaterial, and co-constitutive relations between humans and nonhumans (companion species). She refers to human and nonhuman bodies as ‘transspecies assemblages’ when she explains the actants that operate at the level of function in and on our bodies. In this way, she emphasises the fluid, interconnected, and contingent nature of relationships between entities, challenging fixed boundaries and drawing attention to the active agency of various elements within these networks. The use of “transspecies” underscores her recognition that humans and nonhumans are interconnected in complex ways. This suggests that the boundaries between species are not always clear-cut – they overlap, and interaction and dependencies can exist.

By looking at Feminist Phenomenology to explore connectedness in my making and making process, I connected with the writing of Le Guin. Le Guin’s Carrier Bag Theory (1988) challenges traditional narratives of the heroic individual (male) by emphasizing the importance of collaboration, connection, and nurturing rather than conquest. Le Guin provides an alternative perspective on storytelling and research, emphasizing the importance of understanding the complexities and interconnectedness of our world. I have learned from her to be an observer (as a researcher) before trying to change, as by looking, one gets to see what things are in themselves and fall in love with… I think it is about the choice to make time for experience. This process of opening up showed me that interdependence leads to vulnerability and accepting the darker parts and fragility of ourselves and others.

Ecofeminism is based on the belief that the social patriarchal system is the cause of the oppression of nature and women because both nature and women are seen as property liable to be exploited. Ecofeminists seem to call for an ecological interconnectedness between humanity and nature. “The hyper-separation between humankind and nature has contributed to the view that humans are separate from and controllers of nature when the truth of the matter is that humans are part of, bound by and intertwined with the laws of nature ” (Plumwood 1991: 10)

Ursula Le Guin writes about women in an essay, “Woman /Wilderness: Dancing at the Edge of the World, p 162:

“The women are speaking.

Those who were identified as having nothing to say, as sweet silence or monkey-chatterers, those who were identified with Nature, which listens, as against Man, who speaks—these people are speaking. They speak for themselves and for the other people: the animals, the trees, the rivers, the rocks.“

Le Guin gives us this vivid description of women and nature being considered inferior to white Western men. In ecofeminism, there is an acknowledgement of a close relationship between women and the natural world because of their history of oppression. Bellacasa (Matters of Care p 87) reminds us that where there is a relation, there has to be care. I took that an ontology grounded in relationality should consider that interdependence needs to acknowledge heterogeneity. In this way, ecofeminism shows a sensitivity to environmental implications and gender and cultural questions. Donna Haraway referred to dualism that has been persistent in Western traditions, which relates to the practices of domination of women. When she mentions a list, such as self/other, mind/body, culture/nature, male/female, civilized/primitive, reality/appearance, whole/part, agent/resource, maker/made, active/passive, right/wrong, truth/illusion, total/partial, God/man, she wanted the understanding to be there that the first term in each pair was primarily defined in opposition to and with the implicit superiority over the other: being hierarchical dualism. Haraway sees this as a mutually defining understanding, as the one term is lesser or inadequate. I therefore assume that men have chosen to place women and nature in this position. I understand that ecofeminist theory does show some discrepancies towards the views of Haraway. However, I would focus on the resonance with care to continue interweaving these relationships.

Post-Humanism guided my acceptance of the agency of materials and recent learning that I have a phenomenological (bodily)experience of making and needing words (or language ). When reflecting on my making with feathers as a daily drawing practice, it also became a way to deal with personal loss, and feathers became a metaphor for coping with loss, uncertainty and death. The work explored daily drawings of a feather and later developed into an installation made with feathers and other paintings with feathers and containers. I consider this to be about my body, and working with non-human matter was something to explore. At that stage, the idea of making containers for my thoughts was contemplated, and I believe it was a natural shift to look at nests and consider making them.

Looking at the drawings and paintings of mycelium that I created earlier in my making seems helpful in the bigger picture, that is, to show a human search for understanding connectivity. There is no one route, and work is not made in an order like a map. It is for the viewer to choose what to follow and find or make connections. With the weaving of nests, the same thoughts come to the front, and meaning was found in making choices around material and the way I create or try to find form in constructing a nest. I find that by making nests, I am fully involved. This making process with materials took me to how I envision making with the other differently. I am merely attempting to weave a nest; the making is complex, and I must embrace mistakes. It has the potential to become performative by using ideas of documenting. It shows a desire to make with and collaborate with. In this space, I look for the questions that arise from making and I could weave that back into my research. This shows up as being mindful and vulnerable, embracing mistakes, but also becoming a physical act of touching and manipulating, bending and twisting, knotting and unknotting, gathering and sorting. It could also be about an ‘ongoing becoming with’ as Haraway explains (When species meet:p16)

Symbiotic influences on my practice: Learning from others about connectedness

Haraway uses the idea of ‘storying otherwise’: her stories give us the vision to cultivate the art of living on this damaged planet.

“It matters what matters we use to think other matters with; it

matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters

what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts, what

descriptions describe descriptions, what ties tie ties. It matters

what stories make worlds, what worlds make stories.”

—Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble

Research into practices of art research guided me to (a Ph.D. extraction of) Natalie S. Loveless and onto her book, Knowings and Knots (2018). I was attracted to her view of research as a creation project, namely calling it ‘research-creation’. I like to think of my practice as making, discovering and sharing. I would argue that critical thinking often happens when making/exploring work and writing about it. I do think that working with materials such as fungi brought me to a practice where I, most of the time, weave creativity and technical and theoretical knowledge together. This space allows me to be playful, curious, explorative, and solemn during this process. My making starts from explorations and experiences of the self about interconnectedness between human and non-human. I consider that through making, I found words to understand my experience.

I like the idea that knowing and not knowing are embraced by Loveless as it opens the artist to stay with the process. I had the opportunity in my making to allow agency to my materials. This implied not getting frustrated with outcomes which were not how I imagined or hoped. I had to learn to accept making for whatever it was. When I started working with feathers and bird nests, the making became a connection with nature and birds and my gratitude for having a family that cares. I believe the physical actions of weaving the form tell a story of thinking through, making choices about a direction to take, as well as considering the other – the eggs and birds that must stay safe in this environment.

Through making, I have learned much about myself and realised that my projects, being shown as separate (para)-sites, became stories about my gathering and somehow, the making is about how I make sense of life. I remember words that stuck with me when reading Braiding Sweetgrass: I am the woman with the basket, and how I fill it is a question that matters. (Val Kimerer p 177) I have sad and good stories; it is part of a basket of many stories that formed me.

Discussing my work shared as different sites takes me to Rita Irwin, a Canadian researcher who has developed a research approach called “A/r/tography”. This research method references the multiple roles of the artist when the art practice is explored as a site for inquiry. It became meaningful to me that the artist becomes someone who en-acts and embodies creative and critical questions during a research project. I thought it would be suitable (for my research) to understand more about what happens before the work is produced and confirm why I decided to call my different work processes ‘para-sites’. In my opinion, there lies information and knowledge around what happens before art is produced – the processes are shown and discussed/reflected upon. I did not want my making to be seen as theory-dependent; I would like it to be considered mindful, intuitive and discoverable. Haraway suggests blurring science and fiction, and this sits well with my making in my different para-sites, where I hope my making will also be seen as thinking through and gathering ideas within the relationships I have discovered in work with feathers, fungi, soil, rocks, clay, etc.

When I started exploring making bird nests, I became aware of the importance of awareness on a level of being analytical and learning a new skill, but also the emotional of finding ways into something. Ravelling, unravelling, making knots, connecting, weaving, braiding, and gathering became doings and thinking and moved to a vulnerable space as you need to leave room for learning and mistakes. Only when I allowed this space to be a place of ‘no knowledge’ did I become more spontaneous and willing to enable things within my making.

This thinking took me to the non-human, a bird when building a nest: I have seen the most beautiful nests within species and across species. There are many different shapes and sizes: Science suggests each species has a ‘built-in’ plan – genetic encoding to protect and survive (eggs, survival of the young ones) (The Philosophy of Birds’ Nests, by Alfred Russel Wallace p. 413).

Could I contemplate them as expressive creations of the non-human? Below is a found nest of a masked weaver bird, which I collected on a walk here on the farm. Working with natural materials to weave a nest made me consider that using materials should go beyond ideas of using nature; it should turn the focus to coexisting with nature. It reminds me of being woven into and being part of a whole. My making process directs me from being a viewer to seeing things that sometimes go unnoticed.

We experience the world within specific temporal and spatial boundaries. This limitation may prevent us from fully comprehending the non-human, which could operate on different timescales and dimensions. This made me explore my planning upscaling of the work and developing ‘human-sized’ nests as outside installations into which a human can climb and experience a nest.

Artist who inspired my making

Considering doing work outside in nature opened up learning from Land Art or Environmental artists. Work by Patrick Dougherty has been very inspiring. His works are mainly with willow saplings, and I could relate well to a comment he made in 2017 when constructing a work during an artist residency in Lincoln: “….the line between trash and treasure is very thin, and the saplings littering the ground during the building phase may appear to be cluttered piles of yard waste.” This work was called Sculpture in the Wild, and I was presented in an environmental sculpture park.

I have found many artists who work with natural materials and phenomena and can only discuss a few of these when I look at materials used and how contemporary artists explore these in their work.

The work of Nils Udo was suggested during a crit of my work, mainly for his use of scale and its being outside in nature. Nils-Udo moved from painting nature to creating site-specific pieces and working with natural elements he finds on site. He describes his work as a “documentation of a dying world experience.” The Nest” (image: )was built with the assistance of students and other volunteers; 80 tons of pine logs were harvested from a local Oconee County pine plantation, and hundreds of bamboo stocks were carefully organized into a circular structure dug in gardens rich red clay. After two years, the piece was eventually dismantled and the mulched trees were used to fill the large hole partially.

Within his body of work, he works on large-scale installations in public, urban, and rural spaces. What I find connecting with my ideas is that his work focuses on the ephemeral quality of many aspects of nature, and his work captures the way things are at a particular moment in time, knowing that they will constantly change over time. I also read that he believes that his work can help dissolve the wall humans create between themselves and nature and bring the full power and magnificence of the natural world into focus. (interview between artist and Prof. Song: Art in Nature and Schools) I consider his work an embodied interaction with nature and realise the potential of this form of artistic expression.

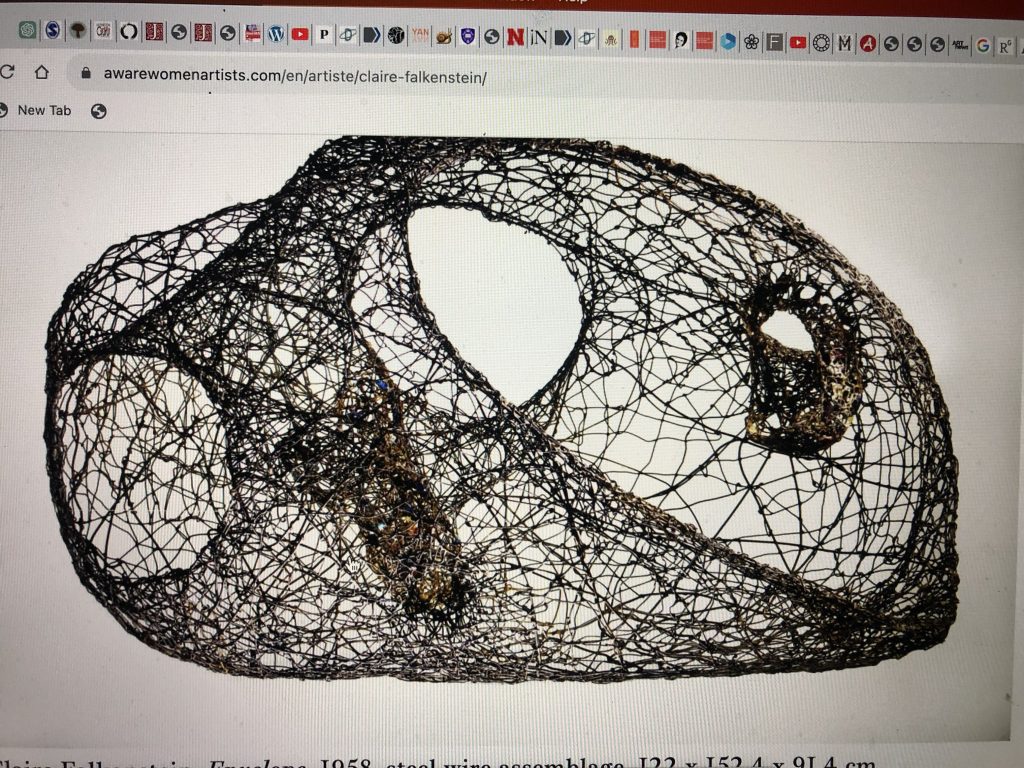

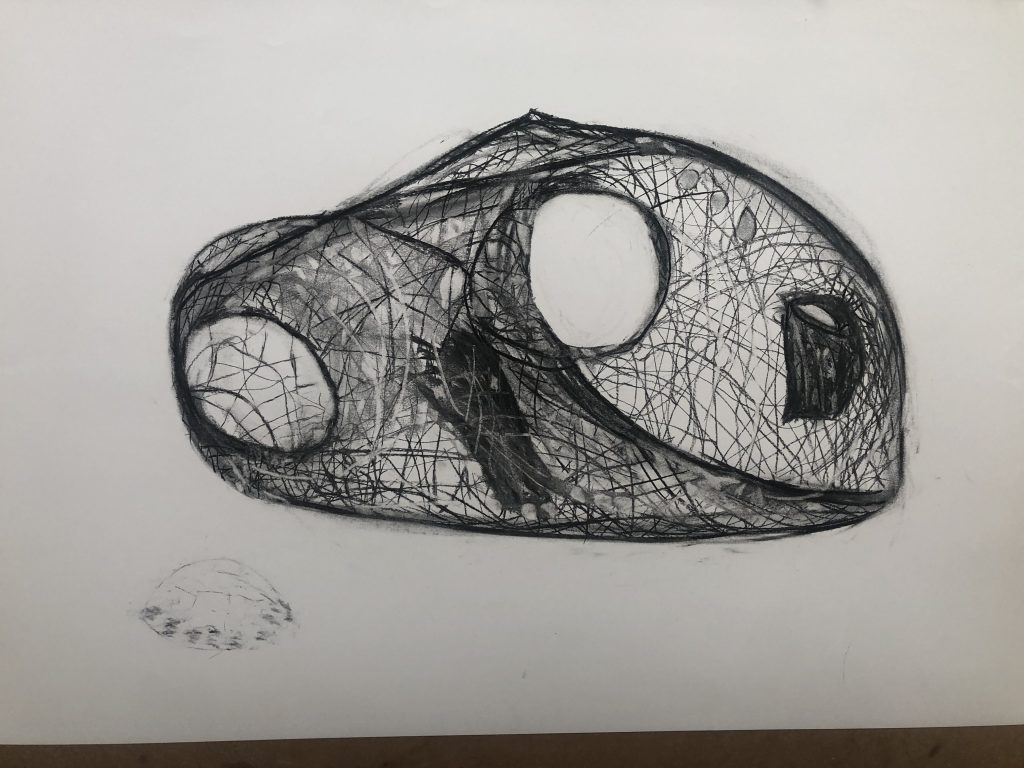

In the work of Claire Falkenstein, I enjoyed her use of various media that were all adjacent to her view. She called her wire sculptures “drawings in space.” She uses themes of scientific concepts and refers to her work’s “Einsteinian” aspects in her bids to evoke interconnected infinity and eternity. I like that the shape or form becomes the connecting idea, part of my making. Her work, Envelope, created from wire and hanging in mid-air, reminded me of a drawing. I read that she intended this piece to be seen from all sides – I can only imagine that one has an experience of the form changing as you move around it – I see outlines (reminds of drawing) and think about how she defines space in this work through hanging it. The form is organic and reminds me of a nest or a cocoon of a larva. I enjoy how it challenges the solid form of traditional sculpture and allows other things inside. The work also placed importance on process – thought during making.

Contemplating real life versus ideal life:

My idea is to consider if contemporary art can challenge dualistic thinking around humans and a perceived position of being in control (at the top of the hierarchy). Can contemporary art embrace the realism of the non-human?

I looked at the origin of the word ecology and an understanding of the relationship between nature and culture and took my view that Charles Darwin and zoologist Erns Haeckel created the awareness of the human being as part of the web of life, and that people began to investigate more intensively the interrelationships between all organisms, and also understood, or became aware that humanity and our technology could be destructive. Darwin opened up ideas about a symbiotic relationship between human and nature. A quote from an essay by Scott Russell Sanders, “Speaking a Word for Nature” (1987), in the introduction of Literature and the Environment (2004: p 7-8), caught my attention. Sanders reminds man that we are animals, in his words: ‘two-legged sacks of meat and blood..’ He described our alienated state from nature as mostly understood only intellectually and writes that it has created a “gospel of ecology” – an intellectual commonplace. He notes that this knowledge (as theories that became wiser) brought a lack of experience (connectedness/interaction) with nature, which implies that humans have become shallower, as it is not yet an emotion alone. “For most of us, most of the time, nature appears framed in a window or a video screen or inside the borders of a photograph. We do not feel the organic web passing through our guts, as it truly does.” This also refers to our continuous strive to stay above and detached from nature in our human-constructed life.

I took a moment to consider D. Haraway’s idea that we have never been human – she believes in transspecies assemblages. This pertains to the fact that we are made up of different bodies of organisms that came together. Some of these are pathogenic microorganisms. One can think of fungal infections in various body areas, or Candida, which can cause candidiasis. Microorganisms, bacteria, viruses and fungi are necessary for our bodies to perform their essential functions and to survive. I consider this experience in terms of my making. Is it about a hybrid body: a body working with non-human matter was something to explore? I wonder about touch when I look at the sculptures interacting with fungi. At this stage, physical contact with the object, whilst the mycelium is still given a protected space to grow, can cause contamination.

I asked myself new questions: What if I consider my studio a space to connect with the outside world? Can it be a container of thoughts as well? If I look at my studio from an outsider’s perspective – lots of things are lying about, things I would like to return to or which inspires me. Is this because I want to hide my vulnerability? Fortnum (2013) writes about the studio’s ability to ‘hold’ a process non-sequentially and make it ‘present’. My human nature says part of showing care is to touch. Touch is a sensory experience at the heart of care or involvement.

By sharing work as visual documentation of found objects and non-human materials, it tells and explores stories of connectedness, care, impermanence, presence/ absence, life and decay/death. My nests are not meant to habitable for birds, but it could house insects and remind humans of the experience and feelings of having or not having a home.

Ingold writes that writing as a practice narrows the gap between thought and expression and makes the critical point that all knowledge-making is participant observation because the investigator is entangled in the world, learning about it from the inside. He questions whether agency should ever have been extended to humans and sees it much better to think in terms of combined actions and flows, where humans get caught up and swept along. “In the art of enquiry, the conduct of thought goes along with and continually answers to, the fluxes and flows of the materials with which we work. These materials think in us as we think through them. (Ingold, 2013:6)

Ubuntu values and matters of Care as an influence on my making practice as a literature study

Bellacasa writes about matters of care as an assembling of neglected things. I took note of her idea when she writes: “I want to discuss ways in which care can count for engagement with “things” from the perspective of critical interventions in technoscience.” (Matters of Care: p 29) She reminds us that these assemblages are knots of social and political interests – they have been socially constructed or embodied.

Considering Le Guin’s Carrier Bag Theory opens up challenging traditional narratives of the heroic individual by emphasizing the importance of collaboration, connection, and nurturing rather than conquest. I think the “Carrier Bag Theory” provides an alternative perspective on storytelling and research, emphasizing the importance of understanding the complexities and interconnectedness of our world. I like the idea of imagining the world by reshaping it, and the power that lies in this way of thinking. Living in a country with diversity and a history of colonialism and apartheid, Le Guin gives insight to: Recognising that there are multiple narratives, viewpoints, and ways of understanding a given topic. Engage with diverse perspectives, voices, and sources of knowledge. This might involve incorporating interdisciplinary approaches, engaging with marginalized or underrepresented communities, or seeking out alternative forms of knowledge, such as oral histories or indigenous wisdom.

I learned that mutual dependence is the ethic of Ubuntu, and in its most robust formulation, it asserts that my very being derives from yours and yours from all of ours. During the transition from a violent colonial apartheid to democracy, Archbishop Desmond Tutu reminded South Africans (and the world) about the ancient African way of life and philosophy of Ubuntu. He described Ubuntu as the essence of being human. It speaks of how one person’s humanity is caught up and inextricably bound up in that of another. ‘I am human because I belong’. In this way, Ubuntu speaks about wholeness; it talks about compassion. Applying Ubuntu gives people resilience. I read the shift from hierarchical to relational to the day’s politics in this. My insight around Ubuntu is that it is a philosophy (African Humanism?) Aristotle insisted on the virtuous function of the human being within the organism or polis. These relations can be viewed as hierarchical, as not all human beings were seen to contribute evenly in terms of their virtuousness and functions within the social order. As a political philosophy, Ubuntu recognises our relationship with and obligations towards others.

Although African morality is generally anthropocentric (or human-centred), it emphasizes respect toward the nonhuman (animal and natural) world. This relates to the belief of many Africans about their unique connections with particular animals, plants, and sacred sites, which may, as a result, become revered symbols, clan totems, or family emblems or may be utilized for healing or general medicinal purposes. African ethics, therefore, emphasizes the interconnectedness of all life, between the human and the nonhuman realms, on the one hand, and the human and the ancestral and spirit realms, on the other (Kwenda, 1999, p. 10; Murove, 2004, 2009). I explore if the relationship with the non-human in contemporary Ubuntu philosophy is focussed on human benefits (being of use to me) and ignoring interdependency as essential.

I considered the role of ecofeminist as my research pointed out that racial oppression looks at how some people see certain races as inferior – to justify domination over them – this was very much the ideas around colonialism in South Africa. My question led me to a South African academic who became a local indigenous farmer and healer, Dr. Yvette Abrahams. I found many articles written by her and want to focus on an article she wrote after she started her organic farming practice. It deals with her personal history of oppression based on race and gender and her decision to become a small farmer, produce organic products, and live sustainably by using indigenous knowledge systems. Abrahams introduces the reader to her world and cultural context from the perspective of a woman and descendant from the Khoesan tribe in almost a storytelling way around soap making and her search for plant materials to make soap. It touches me when I realise Dr Abrahams is a descendant of the First Nations in the Southern part of Africa – here, where colonialism started in 1652.

She writes touchingly about working to ‘decolonise’ her skin, which led to her producing plant-based creams. In our society, skin colour is a complex and painful topic as it contains the construction of race – it is about social divisions, which we still experience. She shares how working the land brought healing: “Slowly, I become once again part of the ecosystem which is my birthright. The wounds left by the loss of land, of knowledge and of bodily integrity are being healed. Waxberry, Buchu and women are re-building community. The land itself is more at peace. We fetch manure from neighbouring horse farms whose owners most fortunately are not interested in gardening, compost it and are slowly building up a living soil. It is becoming more like a sponge year by year. When we take care of the soil we safeguard our future.”

I am open to a thought of Harraway:’ It matters what stories tell stories’, and I take learning from Bellacasa when she writes, “A posthumanist rehabilitation of things needs to remember the wider constituency that this word refers to..” (Matters of Care: p 60).

In pre-colonial concepts of ubuntu, human and environmental exploitation issues are tied in a more holistic worldview, where humans and nature have intrinsic value. I believe the pain caused by Apartheid and the political consequences of it, is still a complex issue which requires care to deal with.

Conclusive thoughts

I want to conclude that research through making as a method enables contemporary artists to understand that art practice plays a huge role in cultural production and has enormous potential to make a difference in the world. Artmaking has become about making connections, having moments of close observation and staying with it.

I came upon a quote by Cicero : “Art is born of the observation and investigation of nature”.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abrahams, Yvette. (2014). Moving forward to go back: Doing Black feminism in the time of climate change. Published in Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity, Vol. 28, No. 3 (101), Gender &

Climate Change (2014), pp 45 -52. Published by Taylor & Francis. Read online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43824370. Accessed on: 8 September 2023

Boyd, Madeleine ( ). Karen Barad;s intra-active Agential Realism: Towards a Performative Multispeies Aesthetics.”

Cornell, Drucilla & Van Marle, Karin, (2015). Ubuntu feminism: Tentative reflections Verbum et Ecclesia 36(2), Art. #1444, 8 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ve.v3612.1444 Downloaded on 30 July 2023

Donovan, J. (1990) Animal rights and feminist theory. Journal of woman in culture and society. 15 (2) p 350 -375.

Fisher, E. and Fortnum, R. (2013). On not knowing how artists think. 1st ed. London: Black Dog Publishing, pp.70-87.

Hart, G., & Slovic, S. (Eds.). (2004). Literature and the environment. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

. Copyright © 2004. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. Accessed online: Created from ucreative-ebooks on 2023-09-15 05:53:14

Haraway, Donna. ( ) The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People and Significant Otherness. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm P, 2003. Print.

Haraway, Donna. ()

Haraway, Donna

Holden, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/sep/10/natural-selection-andy-peter-holden-artangel-newington-library-review

Horsthemke, Kai. (2017). Animals and African Ethics Journal of Animal Ethics

Vol. 7, No. 2 (Fall 2017), pp. 119-144 (26 pages) Published By: University of Illinois Press

Kimmerer, Robyn Wall. (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass Published 2013 by Milkweed Editions

Kwenda, C. (1999). Affliction and healing: Salvation in African religion. Journal of Theology in Southern Africa, 103, 1–12.

Lange-Berndt, P. (2015). How to be complicit with materials. In: Lange-Berndt, P. (ed) (2015) Materiality. London: Whitechapel Gallery.

Le Guin, Ursula (1988). The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. Published by Literary Trust, 2019 with an introduction by Donna Haraway.

Le Guin, Ursula (2013). Talking on the Water: Conversations about Nature and Creativity. Conversation with Jonathan White Coming back from Silence. Published by Trinity Press, 2016 Texas

Mucina, Devi Dee. (2013). Ubuntu Orality as a Living Philosophy The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.6, no.4, September 2013.

Plumvood, V (1991) Nature, self and gender: Feminism, environmental philosophy and the critique of rationalism. Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy6(1):3-27.

Pouliot Alison.(2016.) A Thousand Days in the Forest: An Ethnography of the Culture of Fungi . A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University July 2016.

Puig de la Bellacasa, Maria. (2017). Matter of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press, 2017

Puig de la Bellacasa, Maria. (2012). ‘Nothing Comes Without Its World’: Thinking with Care. The Sociological Review. 60. 10.1111/j.1467-954X.2012.02070.x. Accessed on:

Song , Young Imm Kang. (2010). Art in Nature and Schools: Nils-Udo. The Journal of Aesthetic Education , Vol. 44, No. 3 (Fall 2010), pp. 96-108. Online on : https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/jaesteduc.44.3.0096.