Research point 1

Artists’ studios

I am asked to read two texts and then consider my own working space and its impact on my body

of work. This thinking should then be taken through to the next exercise in which I will explore these ideas more fully.

Thinking about the previous exercise as I have shared about how my studio space looks and how I function in my not so organized space. I added to my reading, the essay by Caitlin Jones

Caitlin Jones : The Function of the Studio

Jones asks me to consider the ‘laptop’ studio as a post-studio practice where the digital and online become part of the working environment. She shares many examples of artists who work online and one cannot but consider the positive ideas that came with this technology – artists can collaborate and share. I am still amazed at my own use of Instagram as a platform to share my making. She mentions artists who showed in their work how the internet as a platform has given viewers and users a ‘different read’, as there is the speed of access as well as easy access available -the impact of this on research is clearly something I understand. I live on a farm, study online, and have never needed to visit a physical library for access to any documents, that I cannot read in a bought book, which I mostly order online, I can access online via Google search engines, online libraries, and apps. Cleary our studio in this ‘online’ way becomes not only a place of production but a place of learning, storage, and distribution. I am very aware of the importance of my computer/laptop/Ipad/cellular phone in my own making as a tool and enabler.

I agree that in this situation, the studio became a tool, a space, a product, and a frame.

To Daniel Buren the studio function as:

- It is the place where the work originates.

- It is generally a private place, an ivory tower perhaps.

- It is a stationary place where portable objects are produced.

The book, Old Mistresses, Women, Art, and Ideology by Parker and Griselda Pollock (online 5 leaves event) is a feminist collaboration.

Rozsika Parker

Rozsika Parker was a feminist and an art historian who died in 2010. In the article, she discusses the transformation of the South London Women’s Centre into a site in which the domestic and the studio overlap, reflecting and commenting on the female experience of the 1970s. In 1973 with Griselda Pollock she formed the feminist art history collective and their books, Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology (1981) and Framing Feminism: Art and the Womens’ Movement 1970-1985 (1987) continue to be key texts in art history and the political contexts of images. Old Mistresses was a re-reading of the historical significance of women artists and their containment. The writers focused on art history’s values, categories, and the nature of its discourses. It seems new frameworks for art were mapped by them demonstrating a different approach to historical processes. The Subversive Stitch (1983), a radical history of embroidery was republished in 2010 and is a unique text in the understanding of relationships between gender and power through the history of material culture.

Bless my little kitchen, lord,

I love its every nook,

And bless me as I do my work,

Wash pots and pans and cook.

This rhyme was printed on a souvenir plate and tacked onto the wall of the kitchen at

14 Radnor Terrace, Lambeth. The kitchen was knee-high in the garbage, old newspapers,

half-drunk coffees, milk rotting in bottles, fag ends and grubby plastic cartons. The

kitchen was part of a project undertaken by six women. For two weeks they

worked together on the South London Women’s Centre, painting it, renovating it

, and finally creating rooms that exposed the hidden side of the domestic dream.

Rooms as images of mental states – from unconscious basements to hot tin

rooftops. Kate Walker says that she purposely used the most trite, stale images associated with women in an effort to bring over their true implications. Upstairs was an all-white, shaded, claustrophobic bedroom: Sue Madden called the room Chrysalis because she intended to use the room as a projection or a space in which ‘to grow and transform’.

Rozsika Parker, extracts from ‘Housework’, Spare Rib, no. 26 ( 1975 ) 38. Parker//Housework//201

One cannot walk away without acknowledging the social history of gendered labor. I am more aware of the division between creative production and daily maintenance, which I think is also playing out in my own making. The difference is that I am ‘in charge’ and doing the caring and labor out of choice, but I sensitized myself for in a capitalist environment, and most challenging male/female stereotypes, it still is a reality that many women suffer. I even think that employing a ‘maid’ to do the work is something to consider more, as in my society this would mean a woman of colour. Artists like Mierle Ladermann Ukeles, Mary Kelly, and Martha Rosler used domestic motifs to call attention to the underpaid and undervalued position of everyday manual work. It is by researching Rizsika Parker and Griselda Pollock that I am sensitized to how feminism focussed on works that utilized bodily matter irony, and references to the drudgery of housework. By doing this they underscored the unglamorous and overlooked position of domestic labor. The working of women, became the work, to use the theme I understood in Merlle Ladermann Ukeles’s art in a previous study of her work during level 2 of my studies.

Art historian Alexandra Kokoli describes the re-appropriation of needlework (textile art) as the “feminist uncanny,” writing: “The return of the feminine bears the mark of its imposed exile, from which it broke free; its scars are what is uncanny and its return against the odds is terrible.

(The feminist uncanny is thus perpetually suspended between revision and revenge.”8 In this regard, the use of textiles during the second wave often employed motifs of secretion, leakage, and bodily margins to emphasise the “disjuncture between imposed femininity and lived female sexuality,”9 mirroring and evoking images used in feminist performance art.)

I think I am wondering if I should look at the studio as a worksite only – about material artifacts of artists, a place where things originate as well as stored. After reading these articles the studio is a site and a subject of making/production. Many of the studios we can visit of well-known artists (some dead) have become a place of animated presence. I have wonderful memories of visiting Monet’s and Rodin’s studios in France. It really is a place that in many ways becomes an archive where much thinking, living, as well as making happens, but with realities such as failure, lack of direction, indecision, insecurity, and even boredom come to the front. I am reminded of a work by Philip Guston, In the Studio, 1975). He talked about having lucky days and reminds me that failure was always lurking. I am also reminded of a screenshot I took from IG (I took a screenshot, 22/12/23) Phyllida Barlow was quoted as saying: ” There’s plenty of art that’s never seen.” For Phylida Barlow artists exist regardless of whether they are seen by an audience – to me this says something about my studio and the need to create in that space. In this article she referred to work that does not have a destination – that is has its ‘loneliness and its sadness about it’. I do like her way of looking at the unseen and unkown as part of the creative act, which is mostly a deeply private experience – but happens within the studio.

I found an interesting online article in FT magzine (Feb 12,2022) (Inside the artists’ studios: from Bacon to Bourgeois and beyond)

Buren, Daniel (1973) The Function of the Studio Translated from Spanish article read on https://eleco.unam.mx/en/the-function-of-the-studio/ (Accessed on 02/01/2023)

RESEARCH POINT 2 (PAGE 51 of study material)

I have to research three of the artists listed and one other whose work centers around collecting and archiving online and in books. I have to record my findings considering approaches and methodologies that might resonate with my own approach and development of the BOW.

Rachel Whiteread and her Post card series

The link to the interview was broken and I found another reference to the work which indicated earlier work that centered around collecting when she would be traveling. In this work there is reference to the interview with Tate interviewer, Brice Curiger. Whiteread refers to the places from where the postcards were collected and how she then made holes in them with a hole punch or Tipp-Ex in an effort to remove space or focus on certain aspects of form within the imagery on the postcard. It is as if these postcards now only tell part of a story, but a new story about loss and memory, or the mystery of the unknown. I like that she took her artistic freedom to change or make adjustments. One would see old postcards as a way of keeping memories of a place visited or a message we treasure, like from a lover?

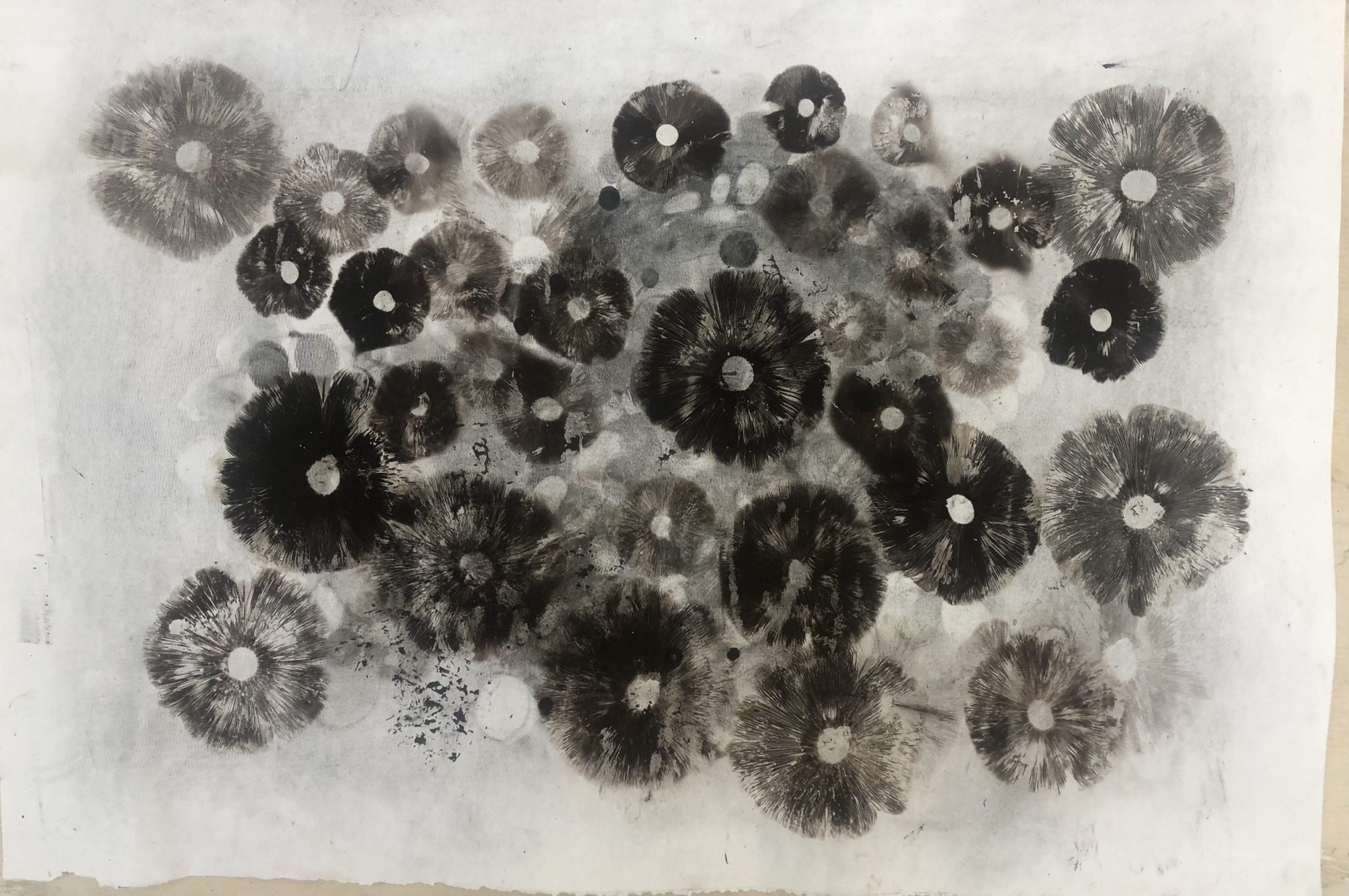

The work reminded my of work I did in my studies earlier. Here I used punched holes on an aluminium plate as part of a hanging installation with mushroom spores. I am again asking myself about traces left behind (the stories they hold) and how much one needs to hide and/or reveal in a work. I also think chance played a role in her work, as in my own – I did not set out how many circles/holes I was going to make and I reworked after I hung it with the mushroom spore work. I do think working in such a space opens possibilities about reflecting on time that passes and memory of place/space.

It does remind me of recent work I started with feathers. In a separate, Exercise 2.1 of my blog I share the process as part of ‘understanding risk’.

Muller, Maxine,2019 Image, perception and the unconscious (MA thesis) https://repository.essex.ac.uk/24973/1/Maxine%20Miller%20-%20Image,%20perception%20and%20the%20unconscious%20.pdf. Accessed on 25 April 2023

Figure . Rachel Whiteread, Untitled (Verso and Recto) 2005, Postcard with punctured holes,

14 x 9 cm (Tate, 2010)

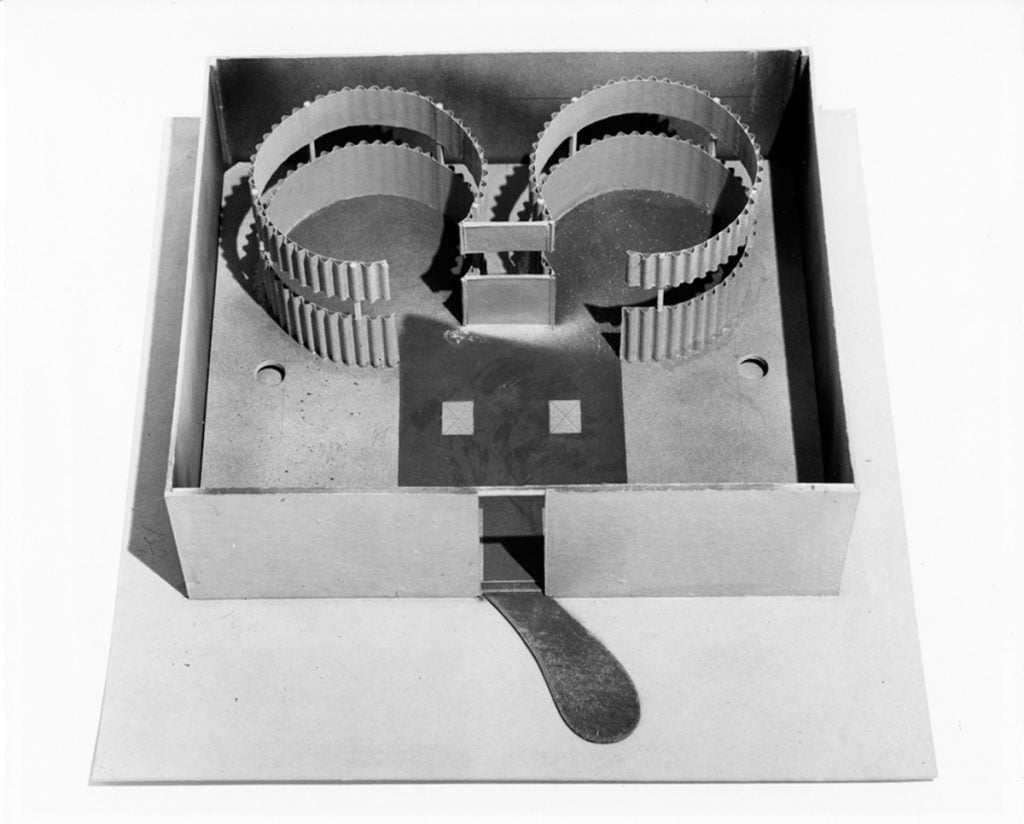

Claus Oldenberg. Manhattan Mouse Museum

When researching this work, I found that he ran two collections, which can be viewed as architectural structures where he presented arrangements of readymade objects alongside various tests and experiments from his own studio. The Tate site describes the work as follows: “Mouse Museum and Ray Gun Wing propose equivalence between collecting and creating while dissolving the distinction between everyday items and museum treasures.” I read that Manhattan Mouse Museum Manhattan gives us a glimpse into the world of the artists as an American Pop Art icon as he tends to an assembly of small curios, objects, and artworks. It seems his mouse iconography manifested itself in drawings and models, in cloth, steel, and cardboard as well as in various sizes and materials. The exterior view of the Mouse Museum, 1965-77, wood and aluminum, was approximately 8½ by 31 by 33½ feet in size. I learned that the word “mus,” in Swedish, means both mouse and museum. The objects displayed were found as well as some made by the artist.

One could view the work as a prototype of the “found art” movement influenced by Duchamp’s “Readymades”. The Mouse Museum reminds of a type of wunder cabinet, and I do like this idea, as I have my own little wunder cabinet in my studio, which I like to fill with made as well as found objects.

Claes Oldenburg: Model of Mouse Museum for Documenta 5, 1972, cardboard and wood, 4¾ by 20 by 21 inches.COURTESY WALKER ART CENTER/PHOTO GEOFFREY CLEMENTS

Ihttps://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1296

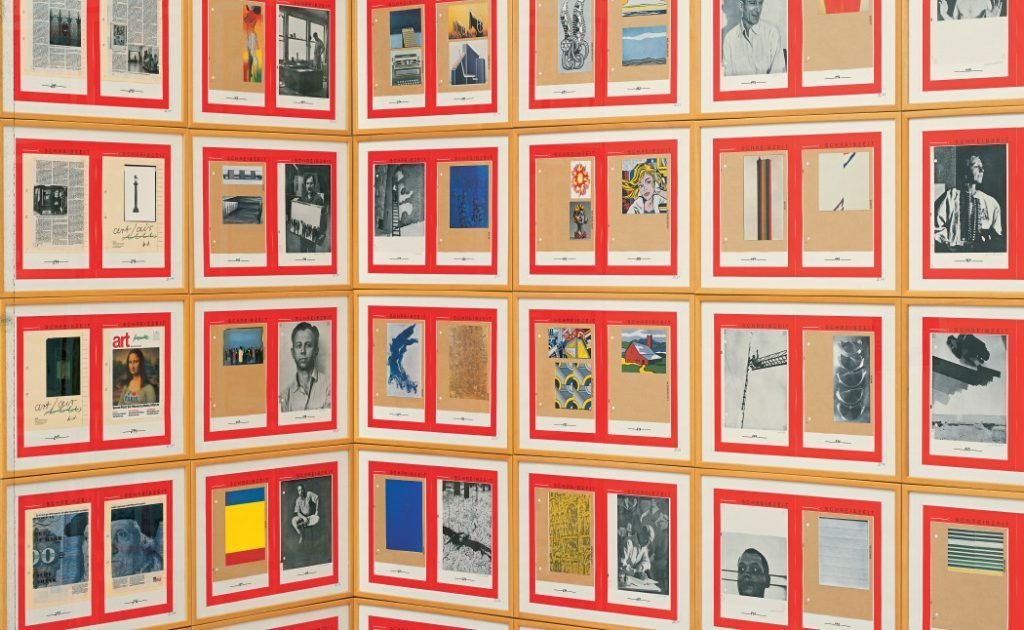

Hanne Darboven – Her first “calendar notes” originate from 1968.

It seems her work is about continuation. On the ArtForum website I read the following about her work:

“The calendar is merely a vehicle, with no other meaning for the work, but by permutating its sequences of order (and leapyearly disorder) through endless cross-sums and progressions, Darboven creates her own time. This time, or timelessness, is what one experiences when experiencing her art. It is a time in which she lives, a time to “write,” as she calls her art activity. And like time, her art turns constantly back upon itself in a circular motion (the circles are sometimes small and sometimes immense); like time, it simultaneously extends an endless line forward, into physical space.” Here I read that she ‘hates to read’ but likes to write. For her numbers is a way of writing without describing.

I found it very interesting that she composed music, called Opus 17A , which is a work for double bass, immediately after finishing the above work, called Kulturgeschichte 1880–1983, 1980–83. This musice was first performed at the opening of Darboven’s exhibition at Dia on Wednesday, May 1, 1996.

Artforum, October 1973, Deep in numbers. https://www.artforum.com/print/197308/hanne-darboven-deep-in-numbers-37981

TATE Papers, Perspectives: Negotating the Archive (Tate Papers no 9. ISSN 1753-9854)

my notes after reading

I think of what is in the works that I have kept over the years, in drawers, files, and shelves, that are significant that I would have kept, but not framed, or exhibit somewhere in my home or studio. Some even traveled to Dubai for 3 years and others were added while I lived and worked there. My phone photos are archived in the Cloud and I have recorded all the work I have made over the years. I started with files that would name groups, such as Landscapes, Portraits, Life drawings, Rhino work, Daily drawings, Assessment portfolios, etc. I am not very good at keeping this organized and updated. Then there are also files with images that inspire me, much like find objects.

I agree these images do not state any of my thoughts or ideas, but in a way, I selected what to keep or discard. I do think of it as stock – but not necessarily in the way a selling business would look at it – I might just feel sentimental, or think I could come back to the work at another time, or find inspiration in the work. The fact that some of my work has been framed, comes to my mind. Is this part of my archival system – I would consider seeing them as part of my ‘stock’.

I agree that the archive designates a territory, and not about a specific narrative. The reference to territory is inspiring to me – the space where the “material connections contained are not already authored as someone’s – for example, a curator’s – interpretation, exhibition, or property; it’s a discursive terrain. Interpretations are invited and not already determined. “.

I agree that to look at the internet and think there is permanence in terms such as ‘auto-archiving’ is an illusion. An archive needs someone to do regular capturing as well as preserving. Thinking that remembering – how we store and retrieve information, is not passive is great. I never really gave much thought to how one is able to confirm the original context and dealing with the provenance of archives is also thought-provoking.

Archives are traces to which we respond; they are a reflection of ourselves, and our response to them says more about us than the archive itself. Any use of archives is a unique and unrepeatable journey. The archive is attractive territory for the exploration of critical theory because of the processes it both documents and enacts, its contradictions and discontinuities. It is also appealing because of the way it both seems to reflect ourselves and yet so clearly does not. Let us not, amid these compulsions, lose sight of what the archive actually is. Carolyn Steedman writes that the reality of archives is ‘something far less portentous, difficult and meaningful than Derrida’s archive would seem to promise’.21 I would say they are meaningful in myriad other ways.

Derrida’s ‘mal d’archive’ can be found in many different people and walks of life. Why do we – archivists, artists, art historians, family history researchers, fans of Sonic the Hedgehog – long for archives? Perhaps because we find ourselves there and we can project onto the archive our imaginings. As with memory, we can be as selective as we like in what we take out of the archive, even while it claims to present the whole story. Those endless shelves of boxes seem to offer an illusion of authority and apparent truth; yet we all know there is no such thing

Both these works offer difficulty in archiving them as they are vulnerable to airflow and physical interaction, such as touching, as well as the paper onto which the sporeprints was made. The nest with found mushrooms is in my little ‘wunder’ cabinet, and the mushroom spore print is hanging in my studio – unframed and clipped to a board. It is both open to airflow and touch and has surely changed shape/form due to not being properly archived. I do find inspiration from them in my current making which is more focussed on kinship and almost representation of ideas of connectedness with the other. I have taken photographs of the spore print and consider printing it as part of the development of the work. This has also led to thinking about how it will sit with feathers. Somebody recently comment that spore prints could look like circular feathers after I added sporeprints onto one of my feather drawings. Doing this work made me ask myself if the feathers (being part of a bird) still share some of the relationships that exist between avians and fungi. It asked me to consider my respect for the other.

I also had to spray fixative on the above work to ensure it can be archived.