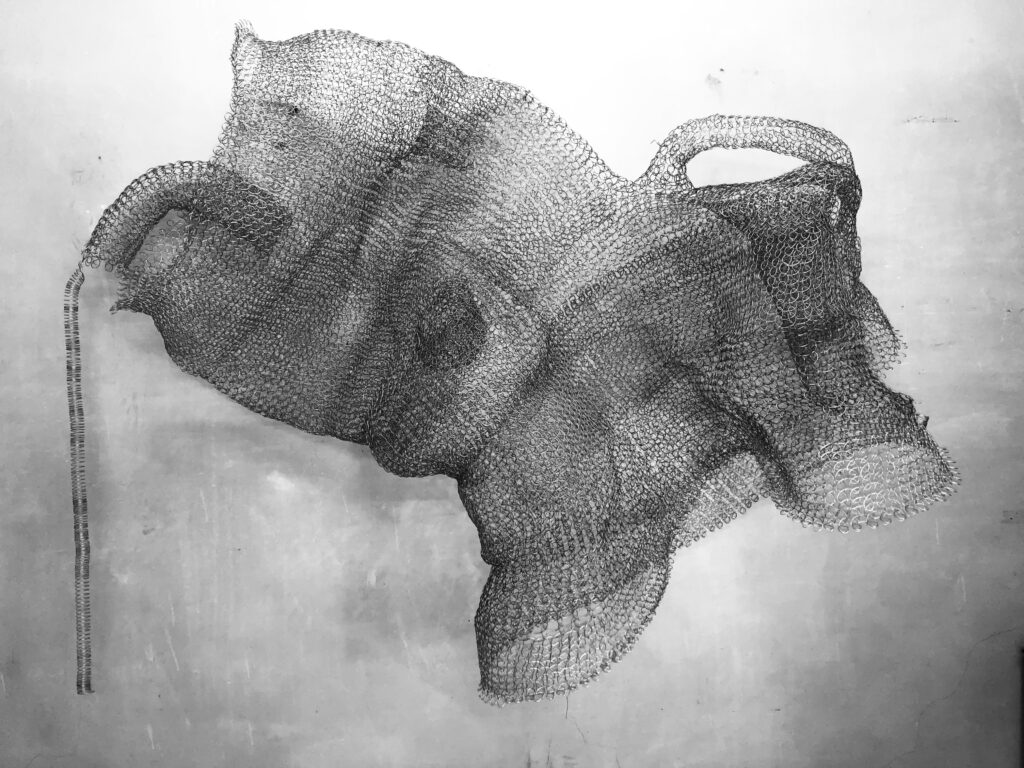

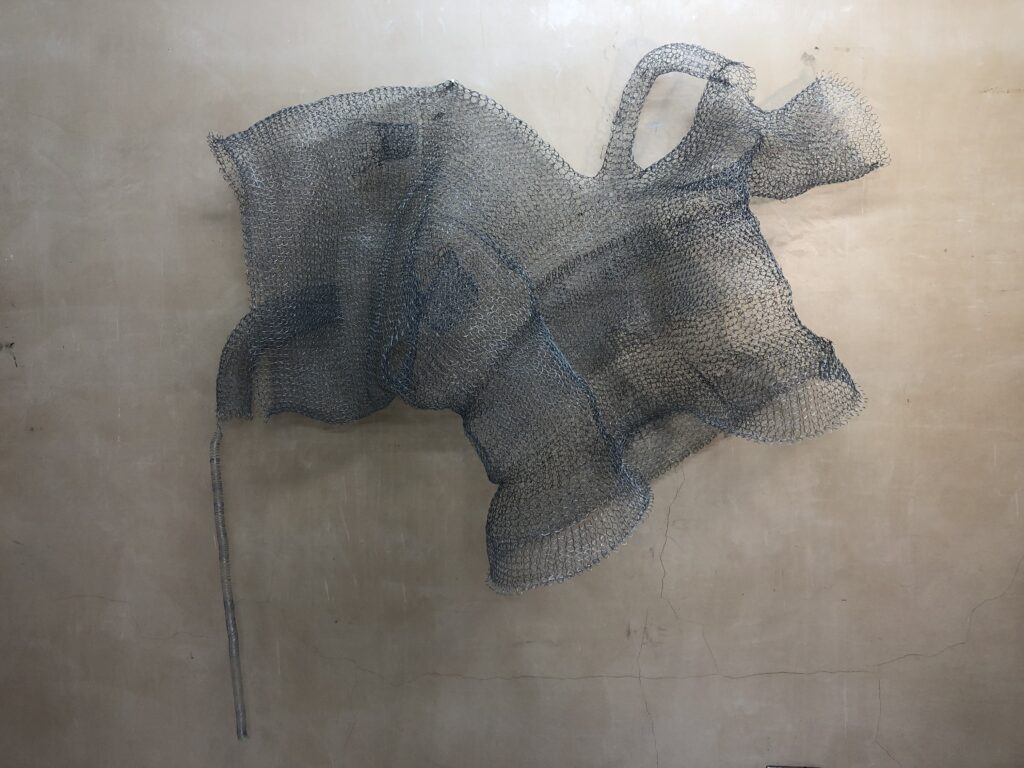

Here are a few views of the nest on my studio wall. I can manipulate the form and make the nest fold over itself when I hang it against the wall. Compared to the idea that wire is rigid, I know the material’s ‘floppiness’. A bird nest in nature comes to mind—this form is solid and maintains its intended shape. (soft and dry materials are interwoven to create the form) I value the transparency of my construct with wire – to always see through it.

At this stage of my making, I consider intention and meaning much more than the technical ability to make it. I am encouraged by the wire work of Ruth Asawa who wanted her viewer to truly see – as if for the first time.

Reading Worringer’s Abstraction and Empathy has provided valuable insights into my practice. I learned to manipulate my wire sculptures to emphasize flatness when viewed from certain angles, creating dense, interwoven patterns that give the illusion of a surface rather than a volume. While my nests remain inherently three-dimensional, I am exploring how wire as a material can reduce a nest to a series of overlapping circular patterns, emphasizing enclosure and protection without detailed depth.

Worringer’s ideas about simplifying complex forms into geometric shapes resonate with me. My wire sculptures can represent nests as physical spaces and symbolic boundaries that offer protection yet impose confinement. This abstraction aligns with the notion of reducing forms to emphasize their essential qualities.

The idea of nests as protective structures can be abstracted into forms that emphasize the boundary and enclosure. This aligns with Worringer’s idea of reducing complex forms into simplified geometric shapes. My wire sculptures can represent the concept of a nest not just as a physical space but as a symbolic boundary that offers protection yet imposes a form of confinement. I want to examine how the ‘breeding chambers and tunnels into the nest’ can allude to that. A student’s reference to fences and cages earlier in a crit session can be explored through drawings or wire works of repetitive patterns and structures. (see collage of earlier drawings where I used the wire fence around the compound we lived in at that moment) During a critique session, he observed that the wire nests reminded him of fences and cages in Cape Town. He noted how people live behind fences for protection on this visit, making the nests seem like secure spaces and prisons. This observation has prompted me to consider the duality of protection and confinement in my work. I never really thought much about confinement, other than when I believe placing a nest in a public space, I would like to ensure that the person there will be safe and that it could not become a trap for criminals to explore. It did make me consider placing the nest in different environments to see how context changes their interpretation. For instance, an outdoor installation in a public space versus a gallery setting. How does the setting affect the viewer’s perception of the nests? Could this reaction underscore the emotional impact of the nests? Could these emotions be amplified through my choice of wire, the scale of the nests, and their placement in space? How will I do this? An outdoor installation versus a gallery setting might evoke different emotional responses, such as safety, fear, comfort, or restriction.

Comments as copied from the discussion: “The chain links of the nests make me think about secure spaces – like chain link fences around properties. I recall my surprise when first walking around Cape Town – all the signs on properties announcing ‘armed response’. So for me the chain links either want to keep people out, so making the nest more secure for the person who chooses to live therin, and alternatively the chain links keep people securely inside – as in a prison, so making sure they don’t get out of their nest.” (D, June 2024)

Fences have specific geometric patterns, and I can create sculptures and drawings that evoke protection and restriction. Below is a ‘collage’ of earlier works, which I will explore. Worringer refers to the perception of surface rather than volumes (illusion of depth and surface). The interplay of light and shadow on the wire form enhances the perception of the nest as a surface rather than volume. This surface illusion emphasises the grid structure, which is also flat.

I would like the grow the size of the nest with at least 30%

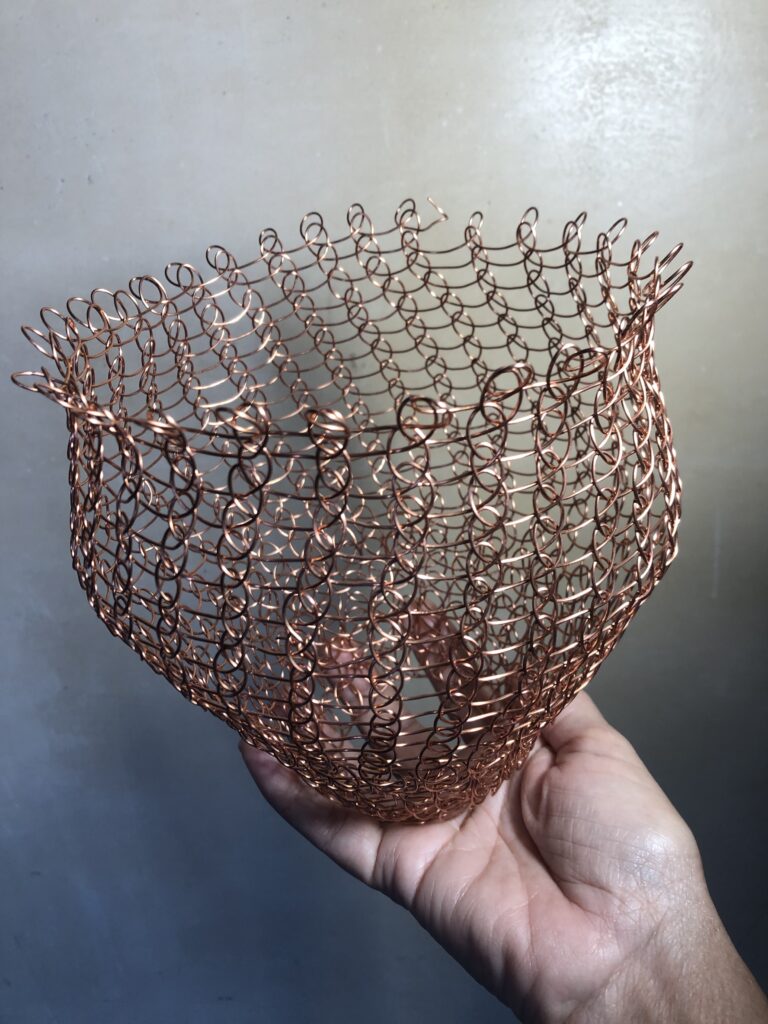

I explored making more vessels with my copper wire. I had to find a new supplier, and the thickness of the copper wire was different from that of the earlier material. Again, this is a timeous process as the wire was bought as insulated stranded electric wire: I had to cut it open from the plastic casing and then unwind the six strands of copper – 15m x 6 lengths! The wire is soft (malleable, too almost figity) , and after working with steel wire for a while, I had to adapt to a softer touch and more delicate way of looping.

The above vessel had three strands (15m x 3) of e-loops with more flexible copper wire. It measures around 22cm in height and 53.5 widest part. I know this is a flexible material as well as that it is less corrosive. I also wonder if this material is not coated to reduce oxidation, only time will tell. I have now learned that the thinner the material the more difficult it is to retain form. Below is a basket made by Ruth Asawa – it is clear how the copper has oxidated over time, but the forms seems in tact.

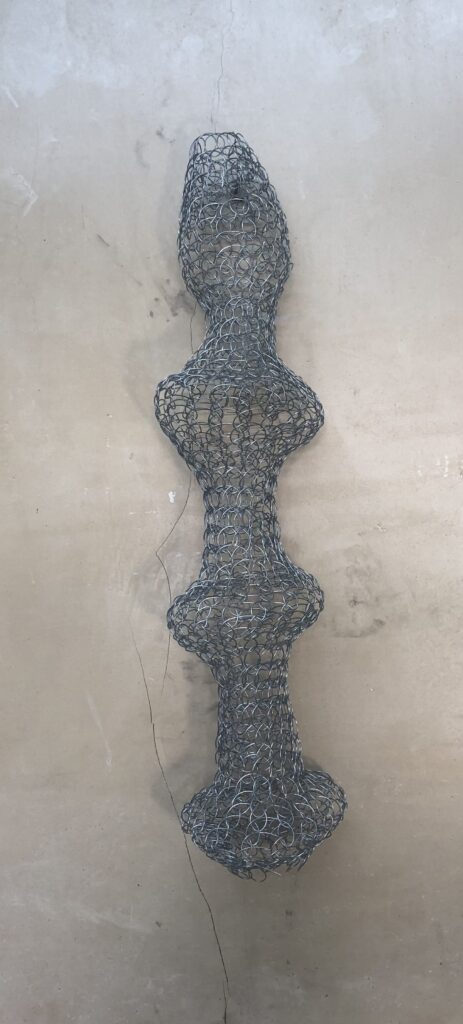

More wire objects 63cm and 50cm

I also looked at French artist Laure Prouvost, who is primarily a video artist who lives in Antwerp, Belgium to ask whether a sculpture becomes a live installation or an installation becomes a living space. I also like that the work plays between reality and illusion, something I have not explored but am considering more and more. Can my nest become a ‘living space’? To me, this is about the complexities of sculpture, or is it about its possibilities? How can the viewer become the protagonist – climbing into the work and experiencing it very physically?

06/07/2024: Add notes after the tutorial on this part: my tutor suggested I read Foucaults’ theories around space