CONCEPT to discuss with Almarie:

THIS IS ABOUT GOING PUBLIC and connecting with viewers of my work. I want a small booklet or online documentation with each piece explaining my process and the themes involved. This would give buyers a deeper connection to the work and enhance its perceived value. This implies that the book is also a ‘marketing tool’ that I can use if/when I exhibit this work in the future. It can enrich how I can approach a prospective viewer/buyer. It will also allow me to see the exhibition as a moment in your ongoing development—a point on a path rather than a fixed destination. It can also serve as a reflective companion. Writing can help me be more transparent about what I was thinking before making it.

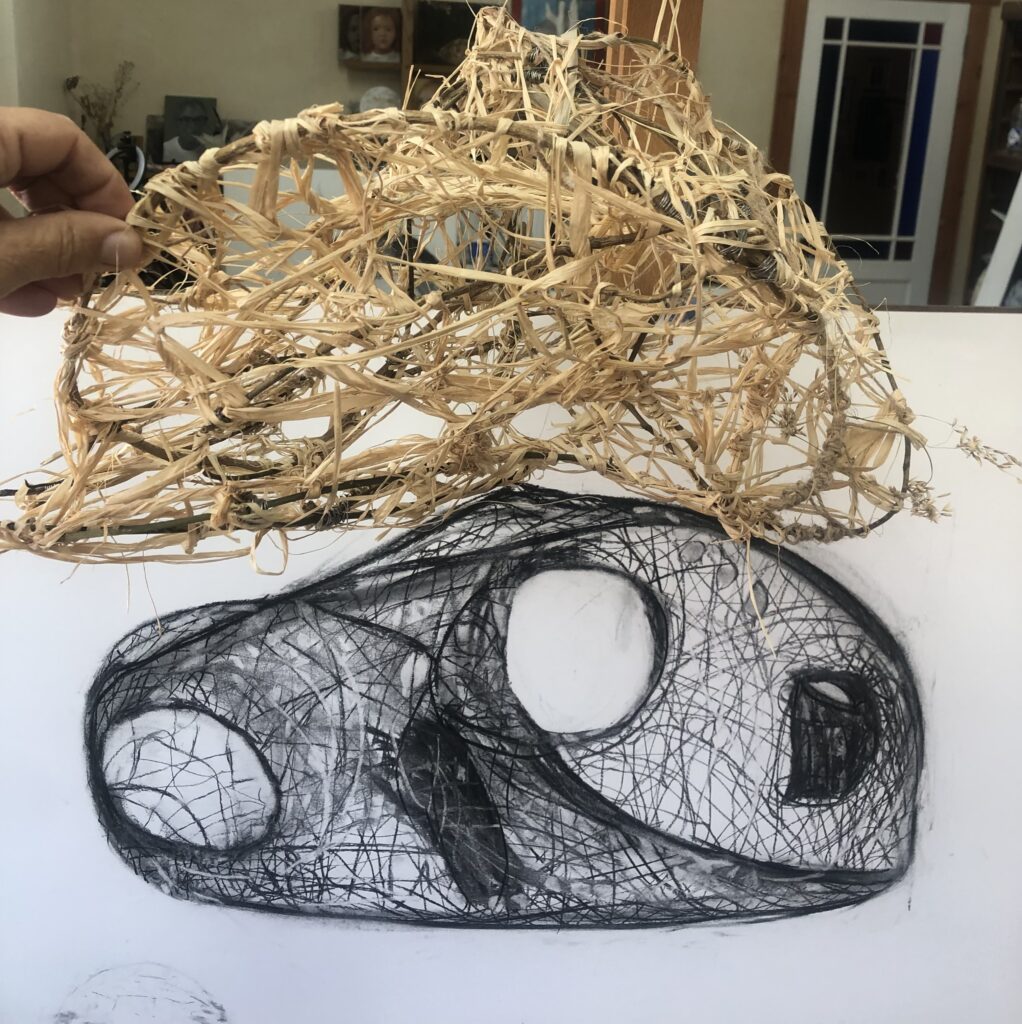

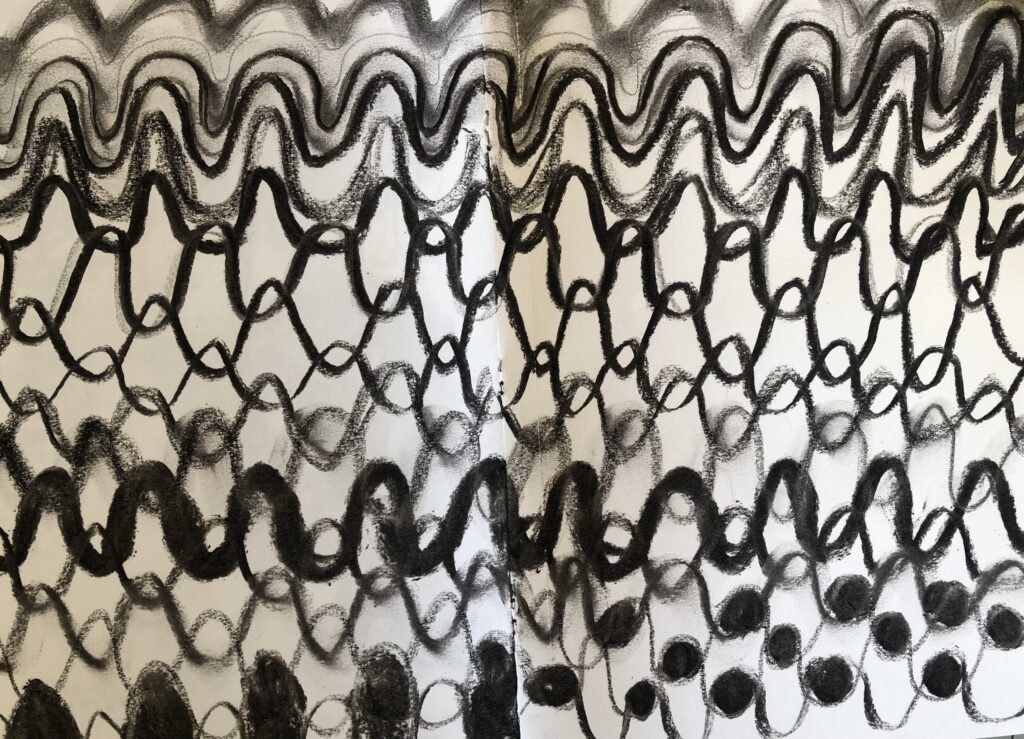

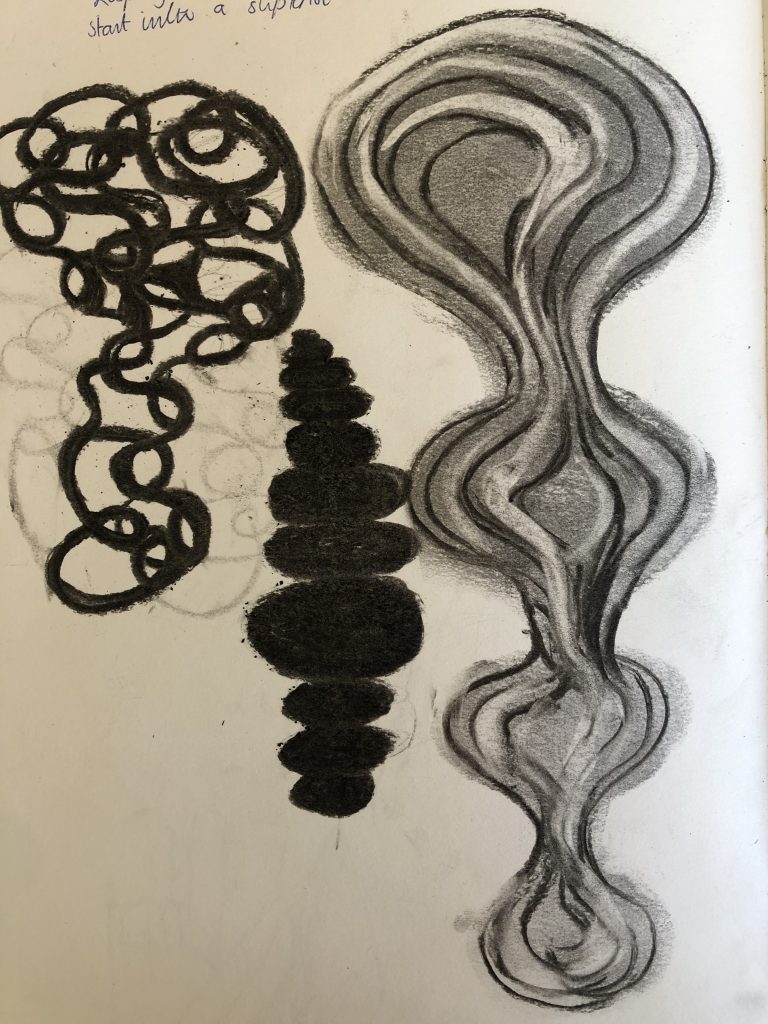

I like the layering in my wire sculptures, and I think layering text snippets and small illustrations (on top of the snapshots) would reinforce the idea of interwoven thoughts and add visual texture.

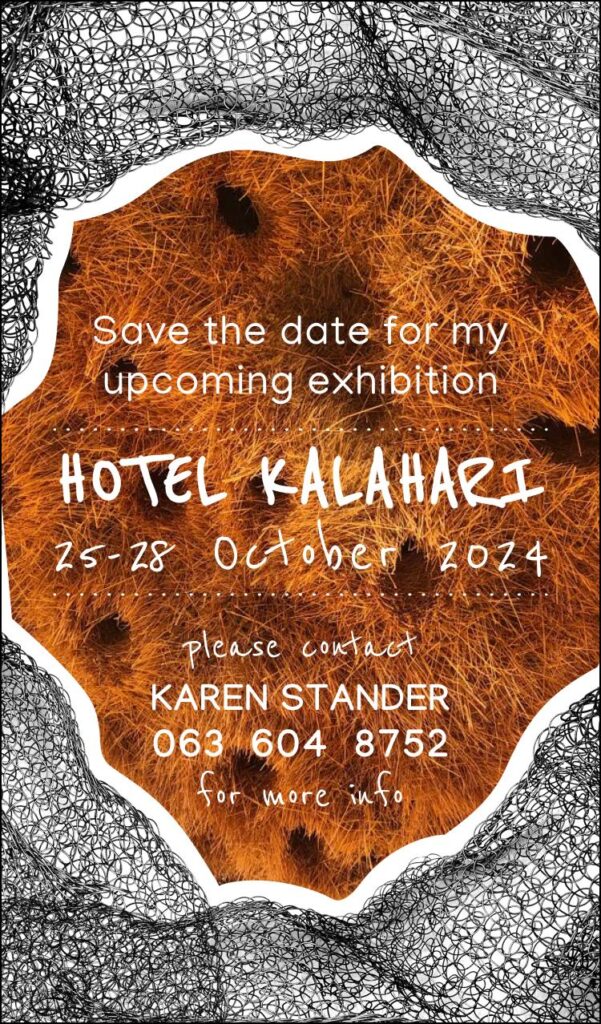

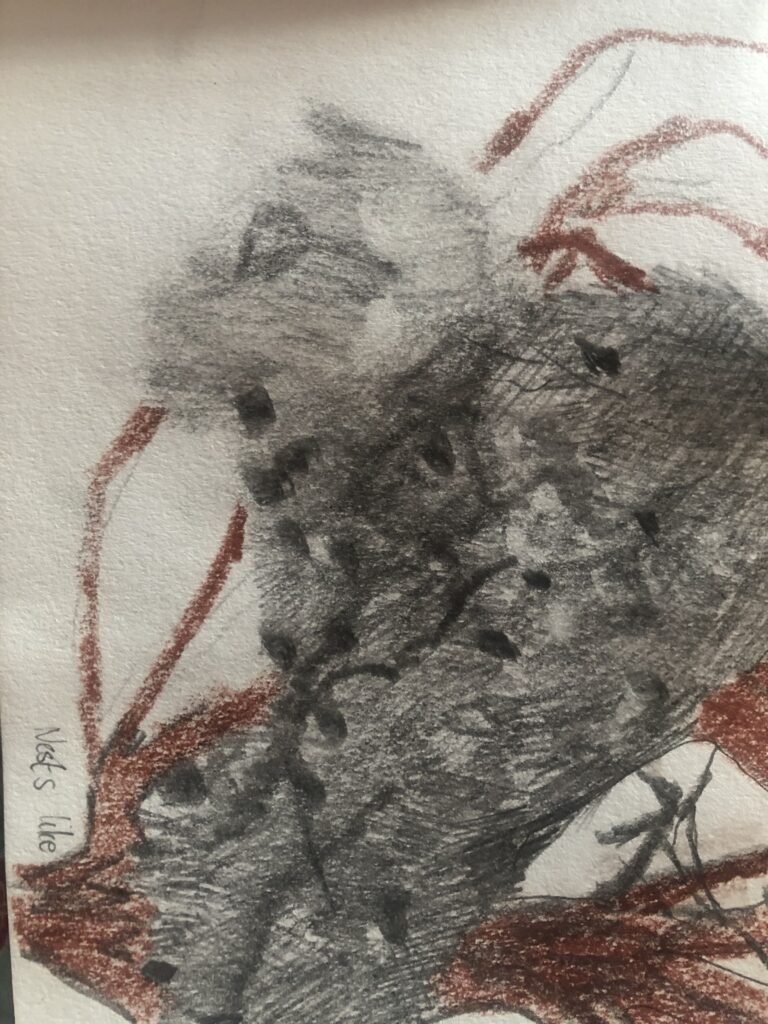

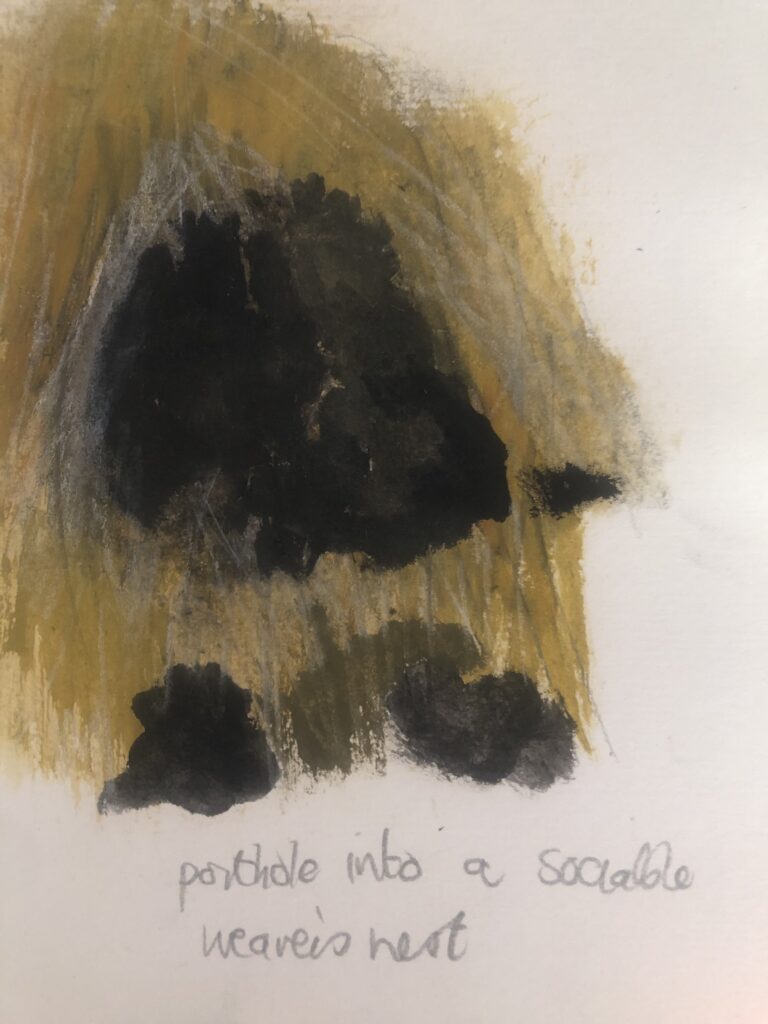

I wanted to use the ideas as we worked around the invitations for the event, where I wanted the nest to be the main focus, but I did not want to reveal the actual wire nest until the exhibition.

My perspective on nest-making—primarily through the lens of the sociable weaver birds—offers an authentic way to connect with the public as the work combines themes of community, resilience, and personal history, inviting viewers into a layered conversation that spans ecology, social connection, and individual vulnerability. Here’s a potential approach for writing about and connecting with the public:

I want to craft a personal narrative rooted in universal themes: Emphasize the link between my personal experiences, particularly around loss, care, and resilience, and the natural world. The way I wrote about the nests during my project motivated me to write a book on this making process: “These nests are reflections of my journey through grief and connection. In making them, I draw on the sociable weaver birds’ communal efforts to build spaces of safety and resilience—essential to their survival and profoundly resonant in human experience.“

Idea for INTRODUCTION:

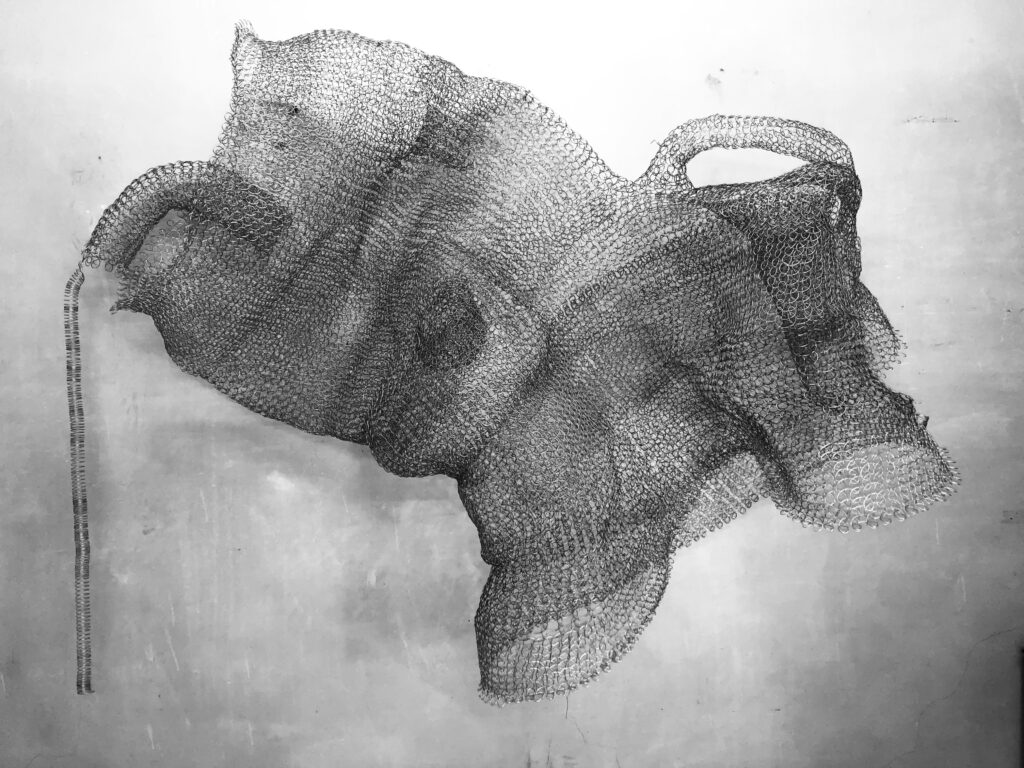

Hotel Kalahari 2024 is an installation combining personal storytelling with reflections on nature through intricately crafted wire nests. Each work has transparent layers that evoke an otherworldly, suspended environment, inviting viewers to contemplate humanity’s innate need for safety and the complex interdependence between species. This work explores ideas of home, community, connection, care, and the delicate balance between protection and confinement.

My nests speak as much to human emotions—grief, love, and the longing for community—as they do to the resilience of the sociable weaver birds. They remind us that human and avian survival often relies on cooperation, care, and the creation of shared spaces where we can thrive together.

The wire nests represent an intersection between human experience and nature’s resilience. They are deeply personal, shaped by my vulnerability and grief over losing my youngest son. Each loop of wire becomes a gesture of care, a response to loss, or a moment of resilience in vulnerability.

In creating the nest, I find myself both caregiver and recipient of care. The repetitive, meditative process of weaving wire helps me process complex emotions and create a space for healing. The nests carry traces of my experience as a mother: as mothers construct safe spaces for their children, I have built nests that reflect themes of care, protection, and loss. By sharing my story, I hope to offer viewers a space to reflect on the fragile balance between care and community.

The medium of the wire itself is essential to this narrative. Solid yet flexible, it allows me to form structures that echo the fluid, evolving architecture of the sociable weaver nests. Much like drawing with a continuous line, shaping the wire enables me to create a visual language of strength and vulnerability.

Sociable weavers construct their nests in response to the harsh extremes of the Kalahari climate, where natural threats like fires are constant. Their communal nests serve as both physical and social buffers, underscoring the importance of cooperation, care, and resilience. My wire nests embody this dual resilience, intertwining personal themes of loss with broader themes of ecological survival.

Inspired by these multi-chambered nests from Southern Africa, I’ve drawn on the concept of ‘heterotopia’—spaces that are simultaneously familiar and otherworldly. These nests, practical structures for survival, embody deeper meanings of safety and restriction. I explore this duality: how what we build to protect ourselves can also create distance from the world outside.

I invite viewers to reflect on how we create protective spaces in our lives and in the broader ecological world. These nests are more than physical structures; they hold emotions, questions, and an ongoing dialogue between human fragility and the endurance of the natural world.

How I met prof Robert Thomson

On 12 July 2024 I reached out to prof Thomson after viewing the presentation below.

Below is the first email and request to use the name, Hotel Kalahari

Good morning, Dr. Thomson

I had the privilege of immersing myself in your captivating podcast, “Conservation Conversation: Hotel Kalahari,” which delved into your research on sociable weaver nests and their interactions with other birds/wildlife/trees in the Kalahari. Your work is truly inspiring, and I deeply respect your contributions to the field.

Social Weaver nests and their habitat have influenced my art project for my Fine Arts Honours degree with the Open College of the Arts (OCA) in the UK over the last year, and I have been drawing and crafting nests using various materials such as grass, raffia, and wire, with a focus on the concepts of interconnectivity and interdependency. I plan to exhibit my work, which will be part of my final degree show, on the farm in the Riebeek Valley in October 2024 where I live in. The wire nest, currently around 1.8 meters long and constructed from wire e-loops, will likely be installed outdoors.

For the contextual part of my work, I have explored Michel Foucault’s ideas on space and heterotopias. His fifth principle of heterotopias, which discusses the system of opening and closing that both isolates and makes these spaces penetrable, resonates deeply with your concept of the theme for your discussion, “Kalahari Hotel”, concerning these nests. I find this concept aligns perfectly with my artistic vision and would like to request permission to name my wire nest “Kalahari Hotel after Dr Robert Thomson.” I will acknowledge your scientific input as a significant source of inspiration.

I await your response. Thank you in advance for considering my request.

Kind regards,

Karen Stander

My first interest in wire work was a work made by Claire Falkenstein, Envelope, 1958. The form is organic, and ideas of formlessness and work developing from a process rather than preconceived ideas drew me to explore 3D work.

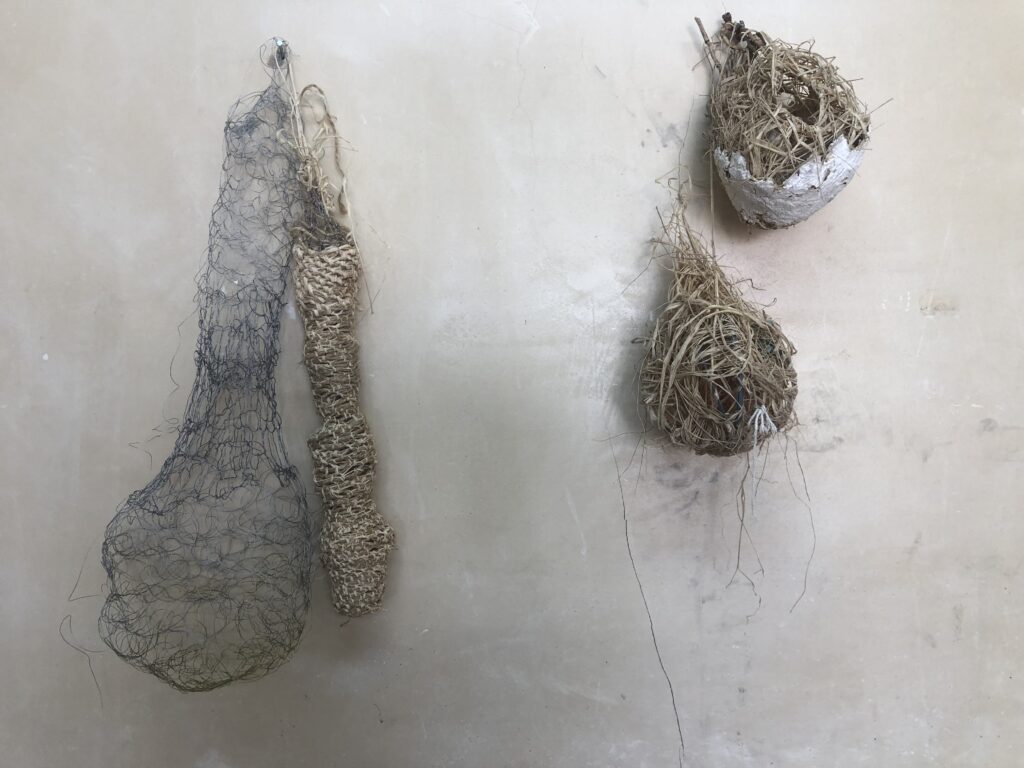

I experimented with using fence wire, which I manipulated into forms resembling Envelope, 1958, and ideas around the building of a nest began forming. I was unhappy with the outcome of paintings of these nests and more drawn to the wire and raffia as my medium to work with.

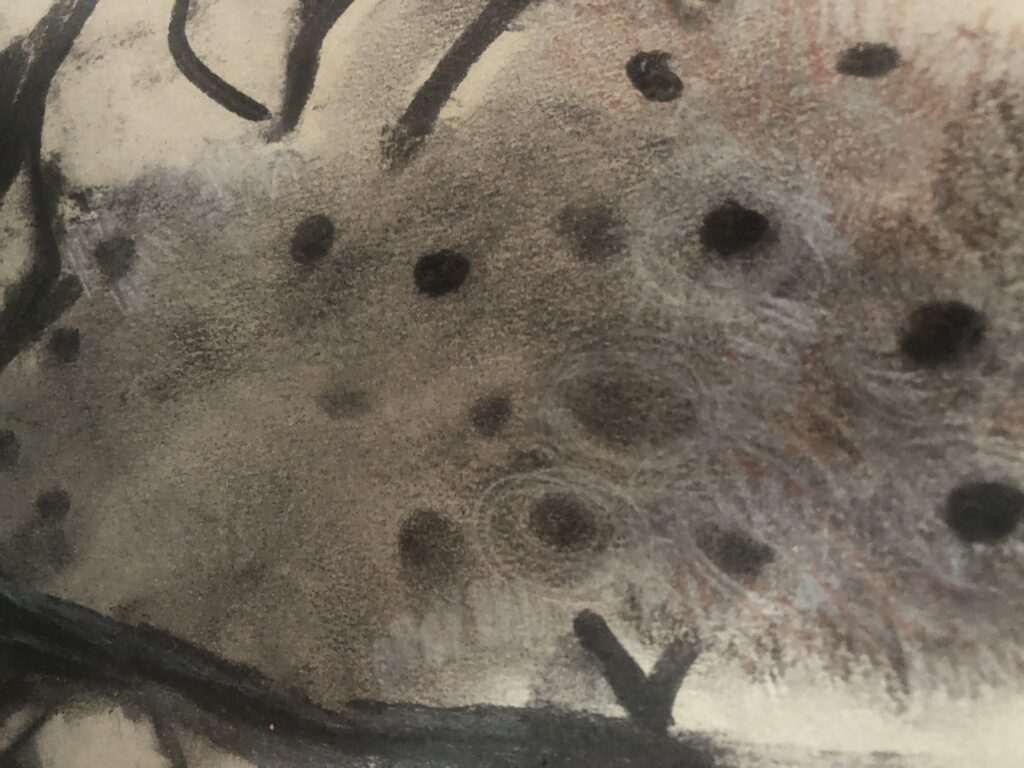

In this process of exploring materials, I researched the work of Ruth Asawa and was drawn to her technique of working with wire. I had to master the wire looping technique and make a few small examples of organic shapes before I tried to work on the nest. By early May 2024, I started to work on a wire nest, and the shapes grew organically. We just returned from a camping trip in the Kalahari and I had great photographic images and personal visits to these nests to inspire my making.

Roots and Beginnings – Context and Field Observations

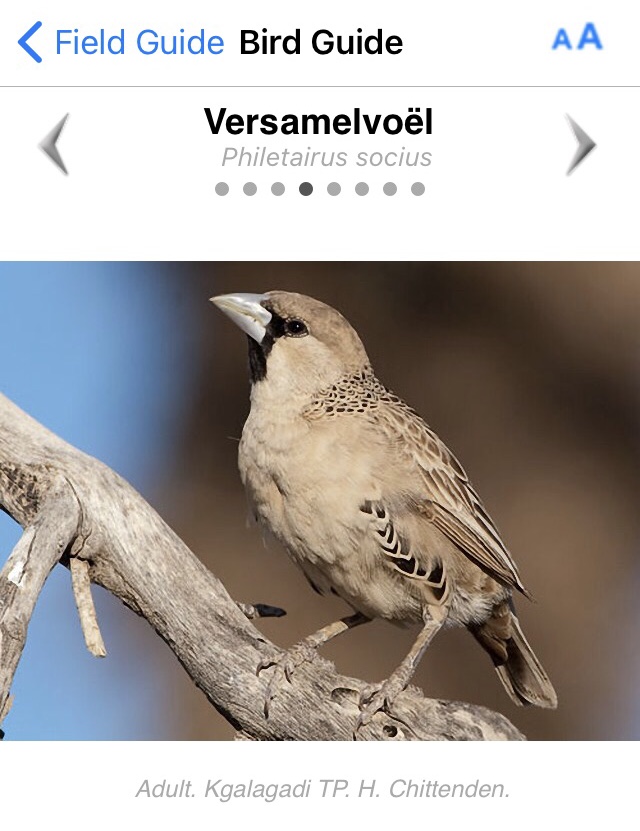

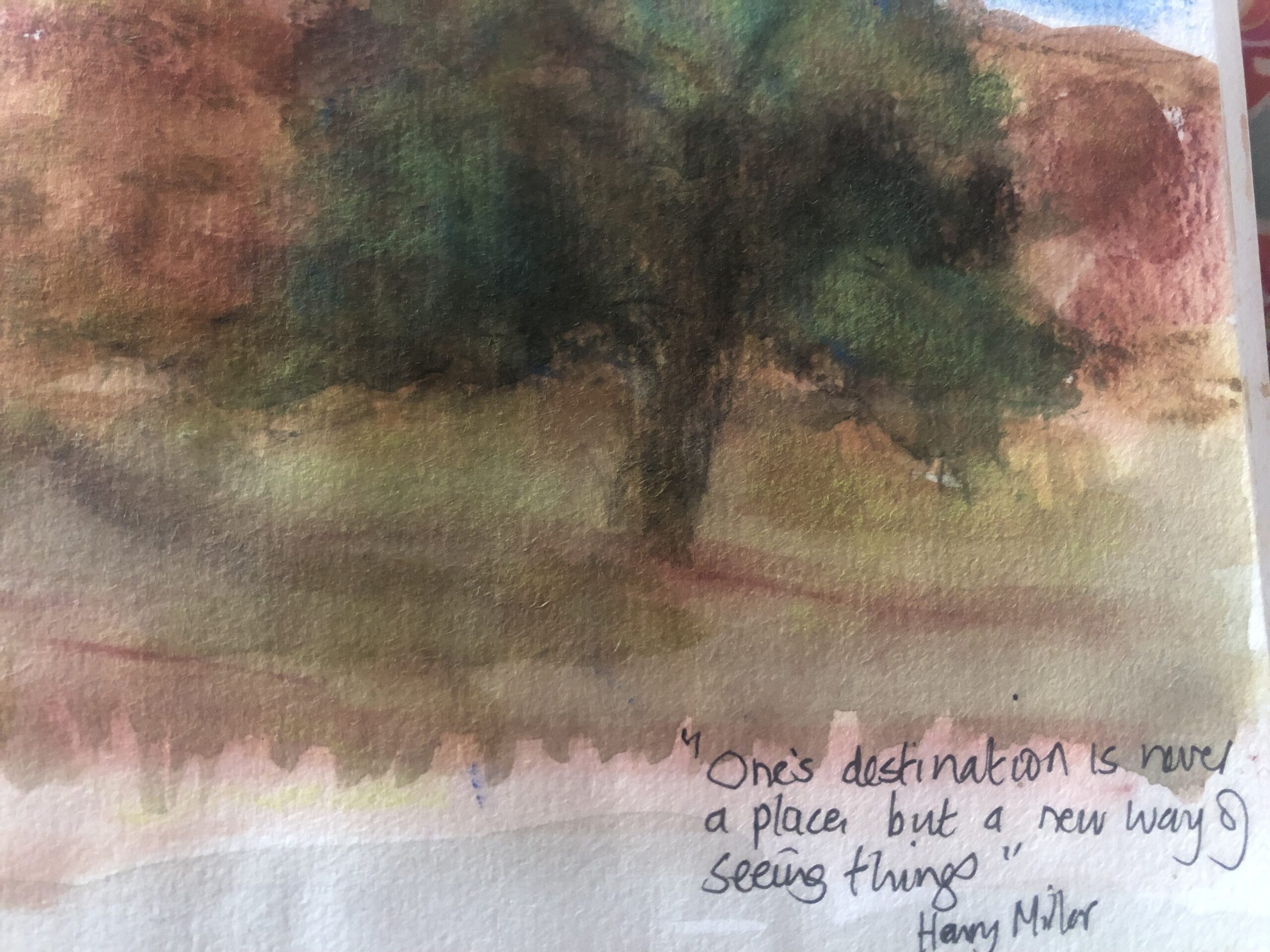

I want to ground the work by introducing readers to sociable weaver nests’ natural history and structure. I want to use this section to set the scene, give context, share field observations and establish a foundation for my connection to the nests. The image below was taken in the Kalahari Transfrontier Park during the end of April 2024. This is a game reserve, and I could only view the nests from our vehicle, as one cannot get out of your car. This visit allowed for sitting quietly, listening to the sounds, and observing the actions around the nest. I learned that a sociable weaver’s scientific name is Philetairus socius. Philetairus comes from the Greek words philos, meaning “friend,” and hetairos, meaning “companion” or “comrade.” This part of the name highlights the bird’s social tendencies and close-knit community behaviour. Socius is Latin for “ally,” “companion,” or “partner,” underscoring the weaver’s collaborative lifestyle. This name reflects the bird’s defining behaviour of cooperation, group living, and shared survival, making it an especially fitting title for a species that embodies collective resilience.

Content Ideas:

Begin with a description of my field visits to the nesting sites, including images and sketches with annotations. I have visited the Kalahari area and Southern Namibia to observe the nests. I always take my sketchbook on our nature trips, primarily wild camping. I will focus on our most recent trip, August/September 2024 and one in 2023. During the trip in 2023, I was making smaller nests, and the idea of creating a sociable weaver nest was forming in my mind as I contemplated upscaling work. Our recent trip to the southern part of Namibia allowed me to get close to nests and observe them. It also made me aware of scientists’ fantastic opportunity to study a group that shares a single space.

I made soundtracks of these birds and reflected on the harshness of the environment and how sharing benefits the collective. In my research, I learnt interesting facts like that, except when breeding, the birds do not necessarily roost in the same chambers on consecutive nights. On a cold winter night, as many as five birds may crowd into a single chamber. Chamber temperatures increased directly with the number of occupants. Researchers recorded temperatures in different nest chambers in a year-long study at the Tswalu game reserve in the Kalahari. They found that the nest’s central chambers offer the best thermal regulation, influencing social hierarchy as dominant weavers often occupy these well-insulated spots. This made me ask about how they communicate, and an exciting discussion during the exhibition was whether there have been any studies regarding the language of these birds. We discussed that studies of deep learning to track individual bird calls within a group could be particularly useful for a species like the sociable weaver. Can it help researchers understand individual roles in a colony and how specific birds contribute to communal nesting efforts?

Consider including scientific and ecological details about the sociable weaver nests and their environment, emphasizing themes of resilience and interdependence. (Robert T research access)

Weaving and Wires – The Artistic Process and Materiality

Focus: Transition to my studio, where I transform natural observations into physical forms through wire sculptures. This section could explore my techniques, challenges, and discoveries in working with wire, light, and shadow.

Content Ideas:

I detail my process of creating wire nests as an echo of the weavers’ methods. I can highlight the techniques, such as layering wire and manipulating light, that parallel the structures of natural nests.

Add illustrative photos of in-progress work or close-ups of wire pieces, with notes explaining how the wire’s interplay with light and shadow brings new meaning to the forms.

Discuss the concept of materiality and why the wire is significant—its strength, flexibility, and transparency in holding both light and shadow, capturing the essence of the nests and evoking layered meanings.

Shadows and Light – The Viewer’s Experience

Focus: Explore your work’s conceptual and physical impact of light and shadow. This section could provide insights into how viewers engage with the sculptures, emphasizing the importance of spatial and sensory interactions.

Content Ideas:

Discuss how we used lighting strategies in the exhibition to cast shadows, making the wire nests feel ethereal or transient.

Share images showing light falling across the wire objects, with notes on how shadows amplify the experience of fragility, resilience, and ambiguity.

Light and shadow also bring attention to how our experiences and emotions, while deeply personal, can resonate outward, connecting with those of others in unexpected ways. The shadows cast by the nest may even evoke the communal chambers of sociable weaver nests—spaces that serve as both shelter and connection for each bird, much like community and shared experiences offer support and interdependence among humans. To emphasize this in the exhibition, I adjusted the lighting to highlight certain parts of each nest and create shifting shadow patterns that change as viewers move through the space. This visually reinforced the themes of interconnection and the layered complexities of resilience, as the shadows appear and disappear like the invisible threads linking our individual lives.

Displacement and Belonging – Heterotopias in Nature and Art

Focus: Connect the nest sites, my work, and broader themes of place, belonging, and displacement, using heterotopias as a lens to consider how spaces are imbued with personal and communal meanings.

Content Ideas:

Reflect on how sociable weaver nests serve as heterotopic spaces—simultaneously natural and social, anchored and fluid. This parallel with human experiences of belonging could explore how shared spaces act as havens or hold constraints.

Address themes of displacement and choice, highlighting how both people and birds adapt to shifting environments, yet rely on communal bonds and support networks.

Tie in virtual spaces vs. real spaces, mirroring the way natural and constructed nests are both “here and elsewhere.” Consider how the digital world impacts our sense of belonging and the simplicity of being present, juxtaposing this with the nests’ physical resilience. Is it about exploring the place? The nests could thus function as heterotopic symbols, embodying both physical and conceptual “places” where nature, memory, and community coexist in layered, sometimes contradictory, ways.

Reflections – ‘Ready-Made Text’ and Annotated Stream of Consciousness

Focus: In this final section, blend my internet research, field studies, and personal reflections as a “ready-made” text. This could act as a portrait of my mental journey, adding a self-reflective layer to my work.

Content Ideas:

I will create a series of annotated screenshots of internet browser history that highlight research sources, articles, and images that informed my ideas.

Include brief commentary or annotations on each screenshot, explaining how the source inspired or shaped aspects of the work. These snapshots add an intimate, contemporary layer to the book, connecting my ideas to a broader conversation.

Incorporate a final reflective note summarizing how the journey with these nests—through field visits, sculptural process, and intellectual exploration—has deepened my understanding of connection, care, and the resilience of nature and art.

Reflections

As Taylor and Littleton suggest, creative identification is “a work-in-progress,” which aligns with my nests’ care, community, and resilience themes. Just as these nests embody ongoing acts of creation and adaptation, my identity as an artist may shift as my life circumstances, priorities, and audiences change.

Highlight:

Symbolism of Materials and Process: Explain the choice of wire as both medium and metaphor. Wire speaks to boundaries and protection but also hints at confinement and vulnerability. Sharing thoughts on the material’s dual nature can invite viewers to reflect on what protection and care mean in their lives. Perhaps “The use of wire speaks to the fragility and resilience intertwined in our relationships and environments—qualities embodied in the nests of the sociable weaver and in our efforts to create safety within a sometimes unforgiving world.”

Invite Public Reflection on Broader Concepts: Through exhibition texts or even conversation prompts in the interactive areas, encourage viewers to think about how the nests symbolize themes relevant to everyone: connection, community, and care. Posing questions or simple reflections alongside my work can help audiences connect my themes with their experiences. For example, “What does creating a ‘home’ in a challenging environment mean? How do we support one another in difficult times?” ( I did not follow through on this – but I had conversations around this.)

Balance Personal and Ecological Storytelling: Connect my journey with the ecological behaviour of the sociable weaver birds. This combination makes your work relatable on multiple levels. I could write something like, “My nests are as much about human emotions—grief, love, and the need for community—as they are about the remarkable resilience of the sociable weaver birds. They remind us that survival, for humans and birds, often relies on cooperation, care, and creating spaces where we can thrive together.”

Position me as a Storyteller of Connection and Resilience: Present me as an artist who brings personal experience into broader narratives about nature and community. Express how my art is a vehicle for exploring resilience—not only in nature but also in human life. This positioning could help audiences see the work as a space for reflection on our shared struggles and connections.

In my thoughts around the above approaches, I consider that it will help bridge a personal narrative with universal themes, making my work accessible, thought-provoking, and deeply resonant for an audience.

In this context, the body of work becomes more than a display of completed works; it also reflects my current position in a continuous journey. This approach could invite viewers to see my art as part of an evolving narrative that remains open to reinterpretation and redefinition. Sharing these reflections with readers might enhance their understanding of creativity’s fragile, evolving nature and the deeply personal connection between life and art.

Through this lens, my learning process in both art and life becomes integral to the exhibition/book itself, acknowledging that external validation is valuable but transient. What sustains creative identity is not external recognition alone but the ongoing, resilient commitment to make and share work that resonates with my lived experience. This approach allows me to navigate changes in my practice with a grounded sense of purpose, even as the external aspects of recognition may fluctuate.