( This blog will be used for the Assessment as I consider the work around the LO for this course.)

Fine Art 3: Advanced Practice (FA6APR)

Learning Outcomes

On satisfactory completion of the unit you will be able to:

- LO1 demonstrate a comprehensive knowledge and technical and practical skills through your work

- LO2 produce an ambitious body of work that is critically informed

- LO3 demonstrate how experimentation has informed your practice and visual language

- LO4 articulate your critical and conceptual knowledge and understanding of a range of fine art and contemporary contexts

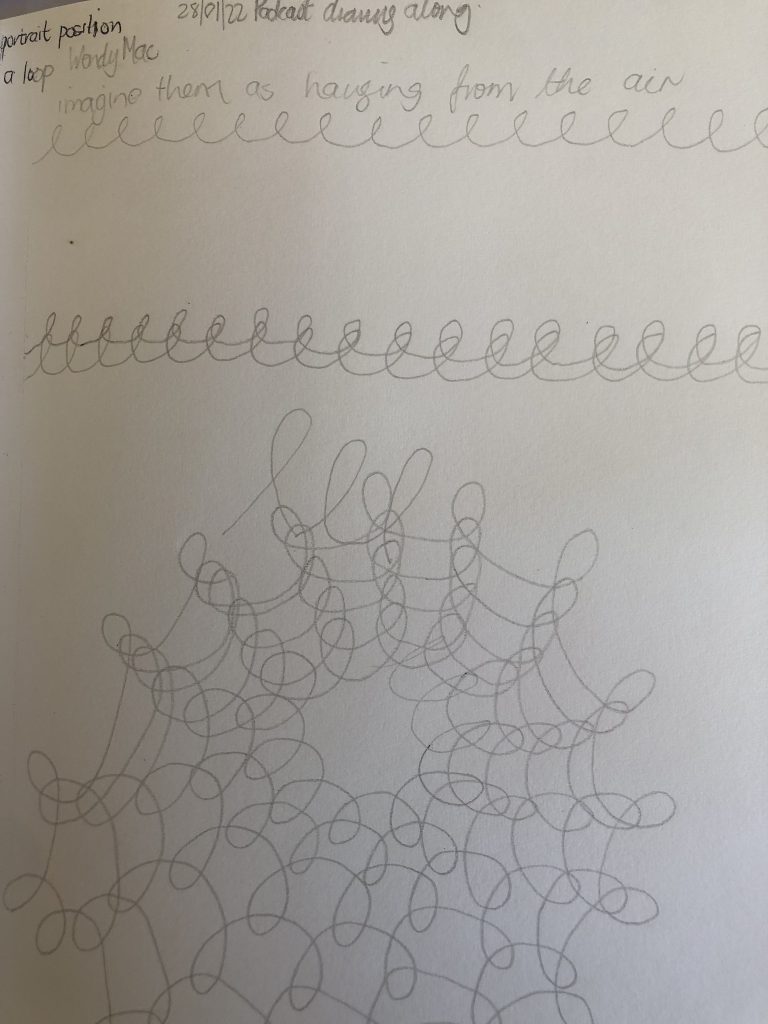

This blog will continue as a space to explore my looping work. I was encouraged to keep making, and for this exploration, I need to develop the required thinking and skillset, as techniques possibly used by Ruth Asawa inspire me. I discussed this with my OCA Eu crit group – here, at least two textile art students reported that they have tried the technique but given up, either because it is laborious and takes time or because the technical skill is challenging. I find that this making is hand-made and as well a labour-intensive process of looping techniques.

I came upon a blog where it was claimed that Asawa herself is quoted in The Sculpture of Ruth Asawa: Contours in the Air as describing her process as follows:

“(it) “is like an ‘e’. You begin by looping a wire around a wooden dowel, then making a string of e’s, always making the same e loop. You can make different sized loops depending on the weight of the wire and the size of the dowel. You can loop tight and narrow or more open and loose. The materials are simple. You can use baling wire, copper wire, brass wire. We used whatever we had. It’s an amazing technique.” (Hoefer, 2006)

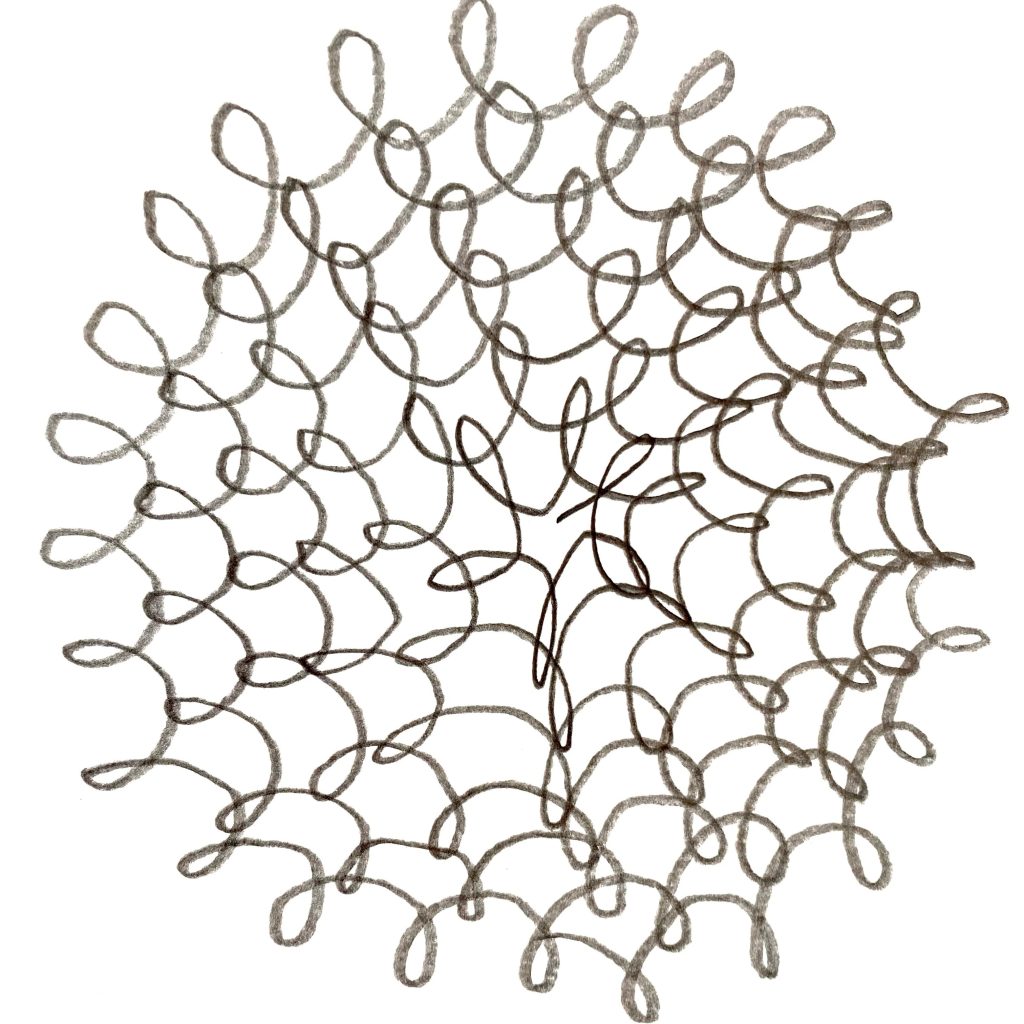

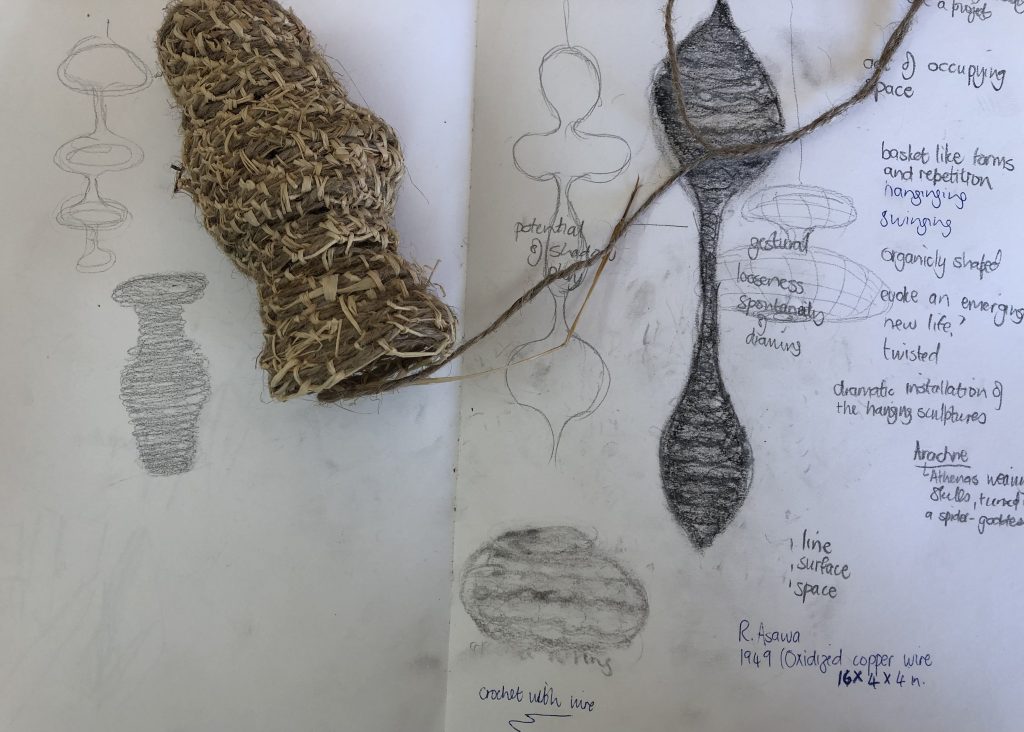

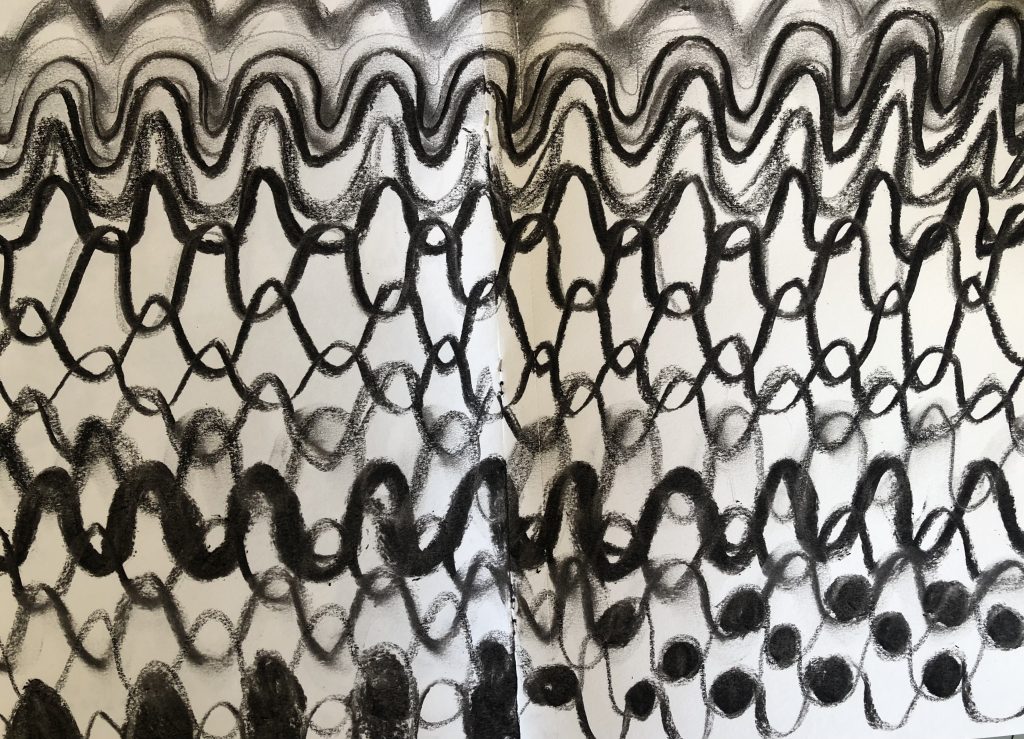

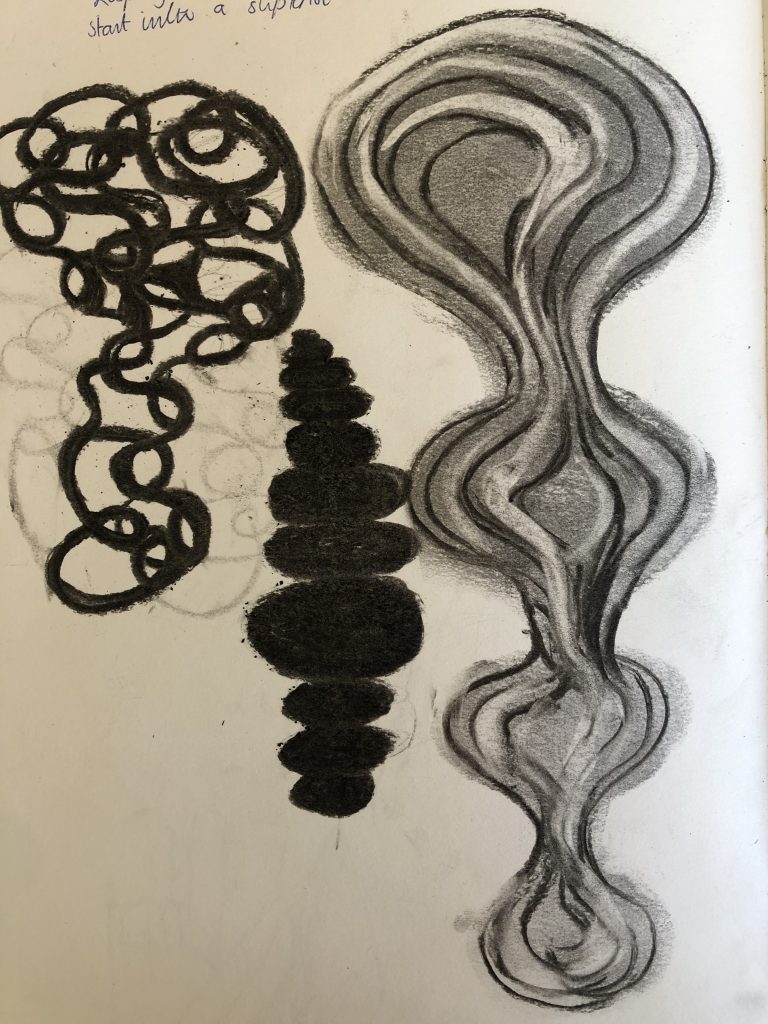

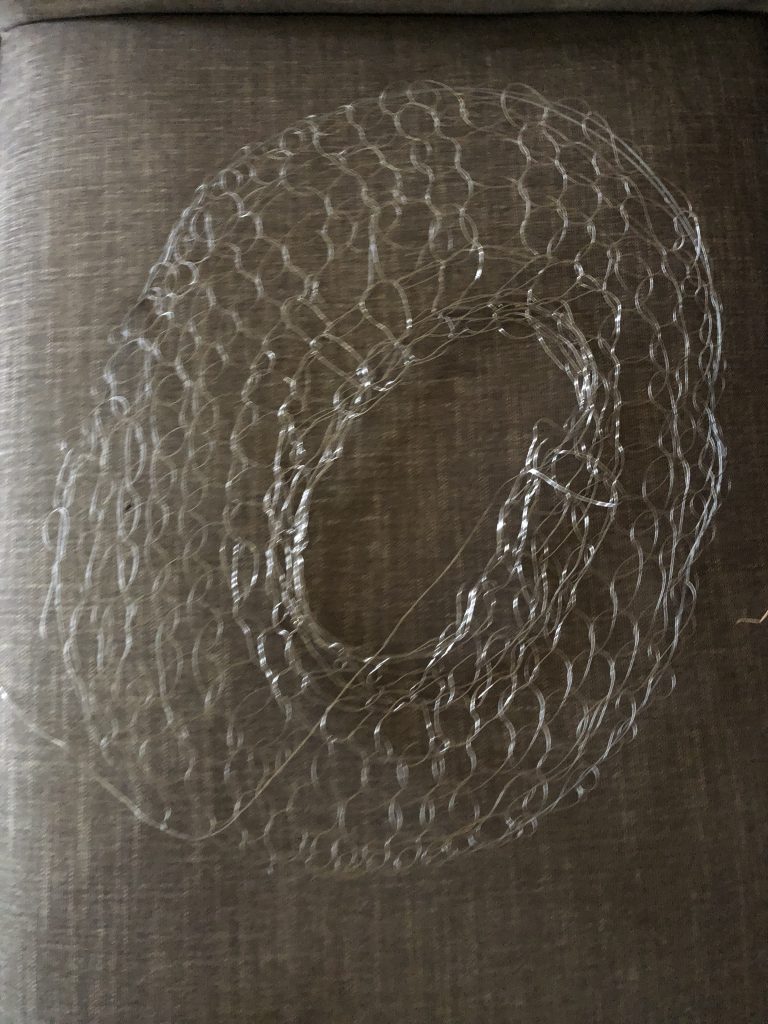

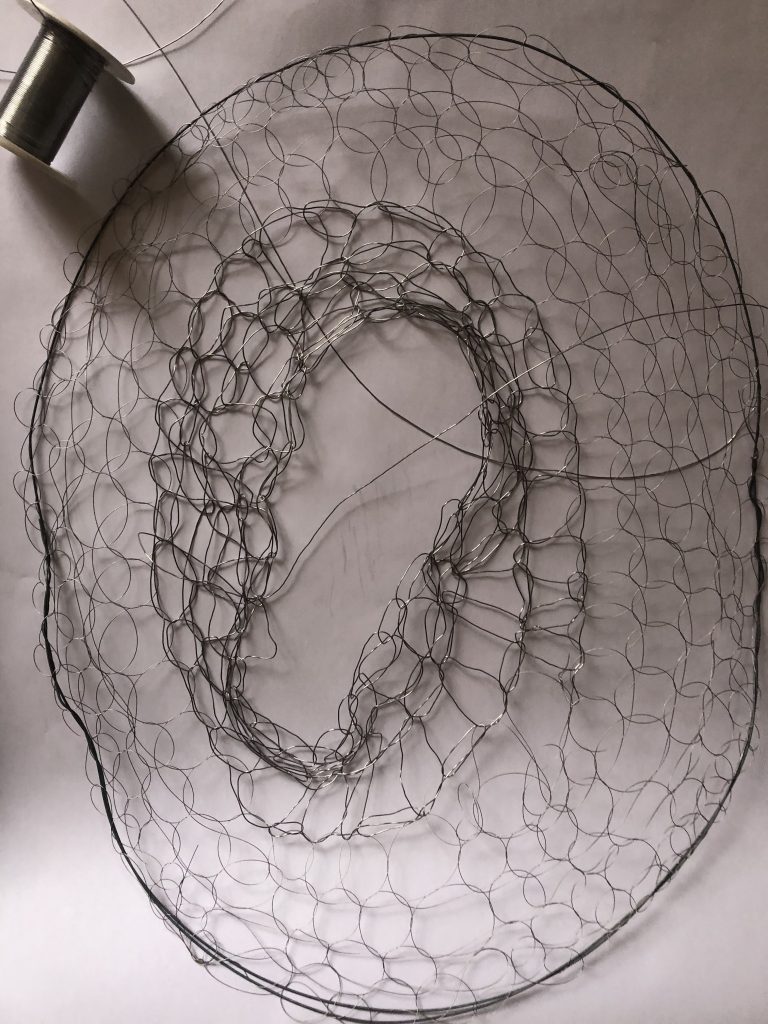

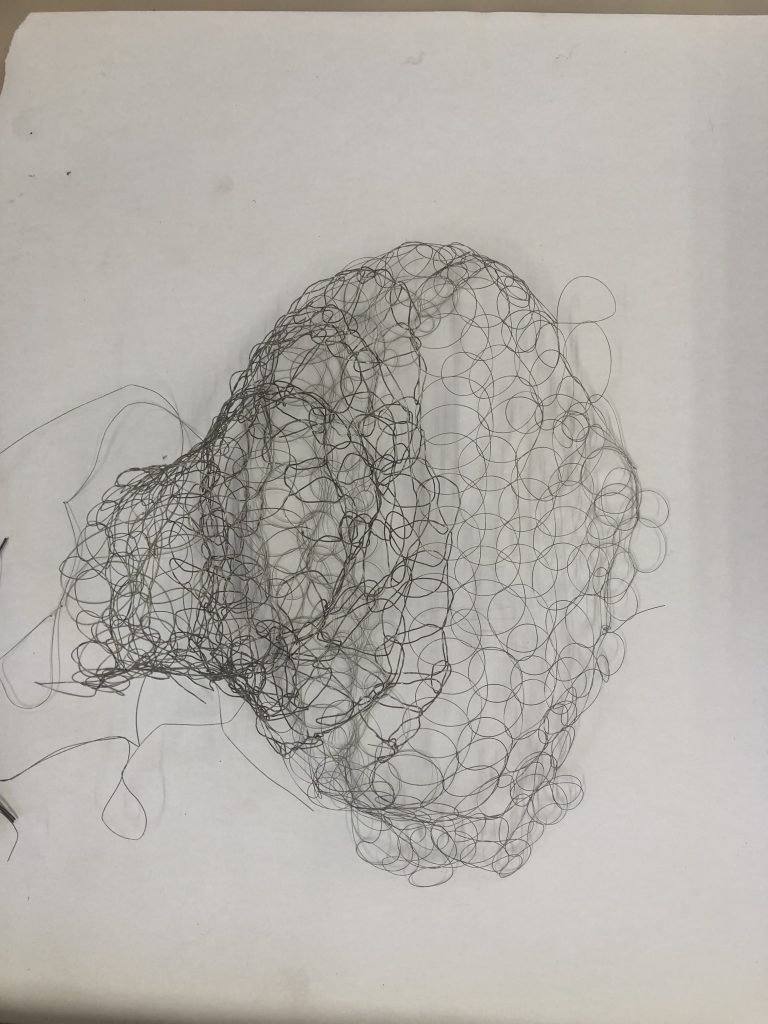

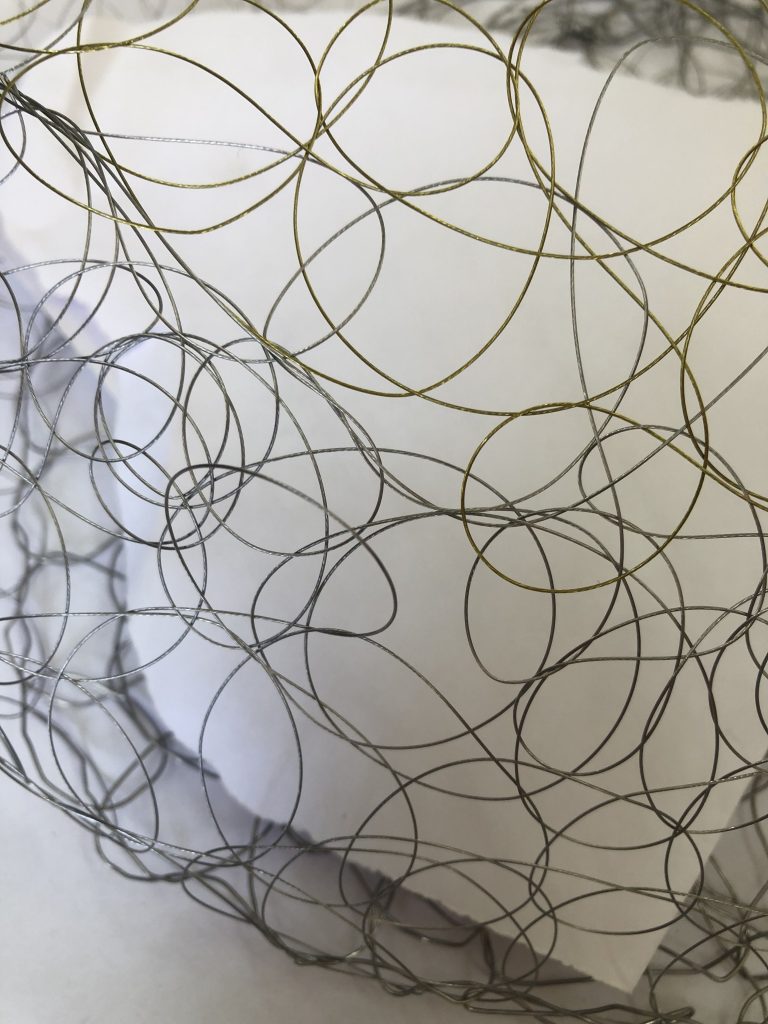

The following images show my exploration of a looping technique with different materials in my sketchbook and material making.

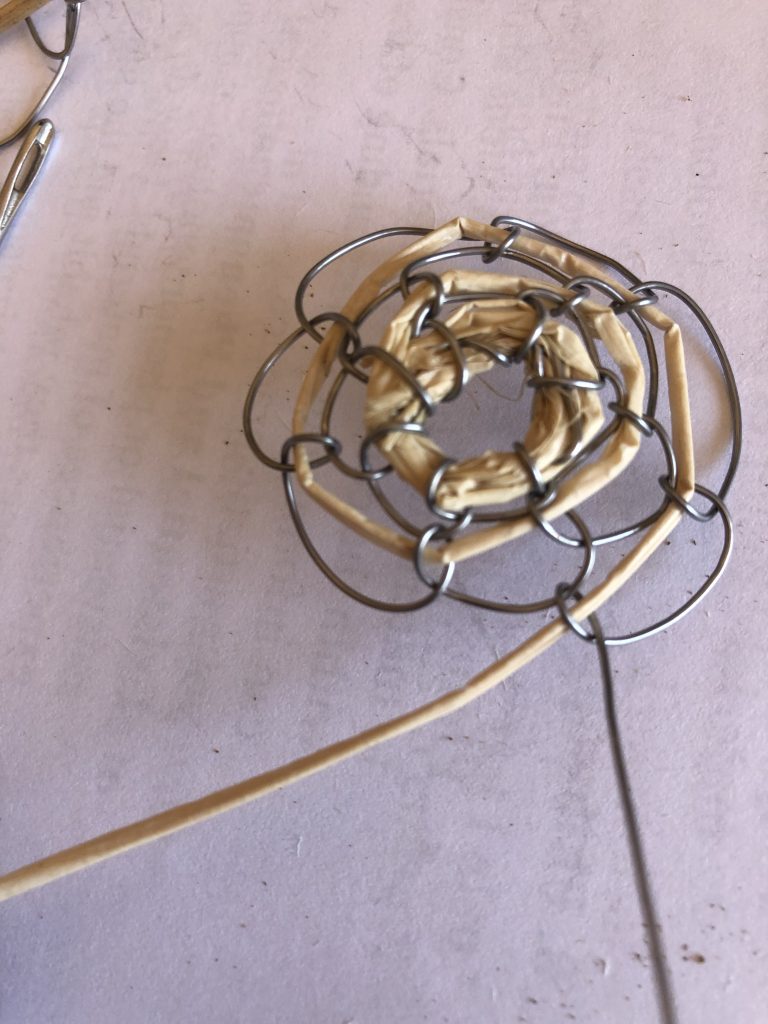

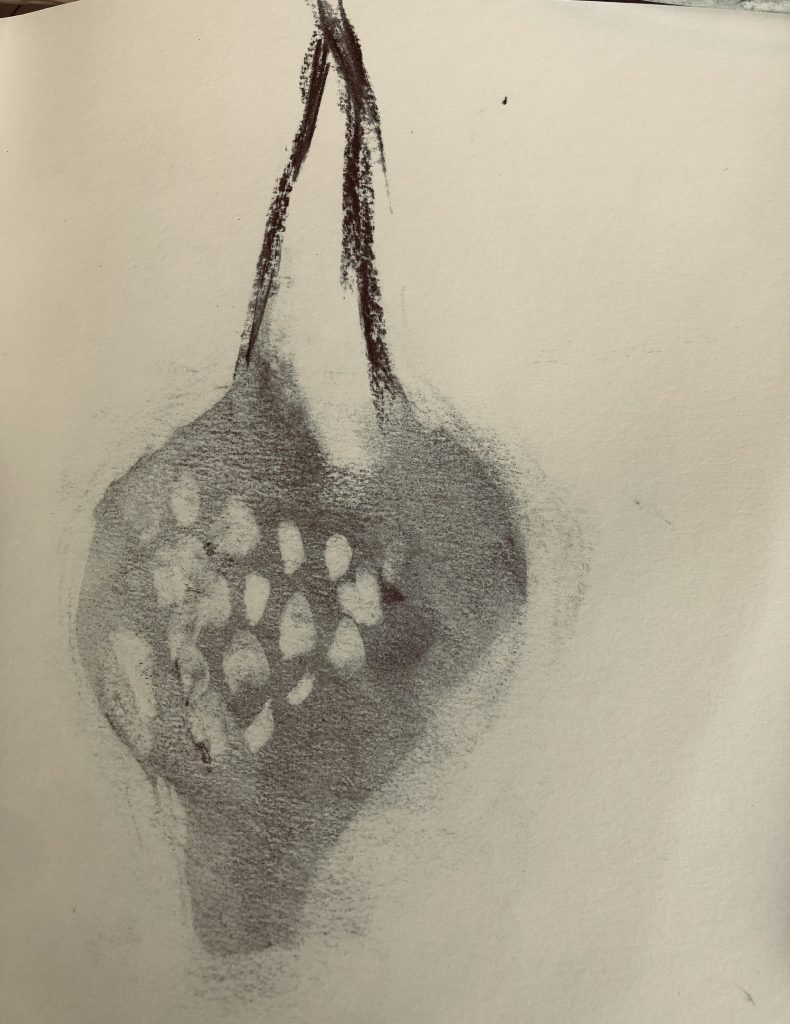

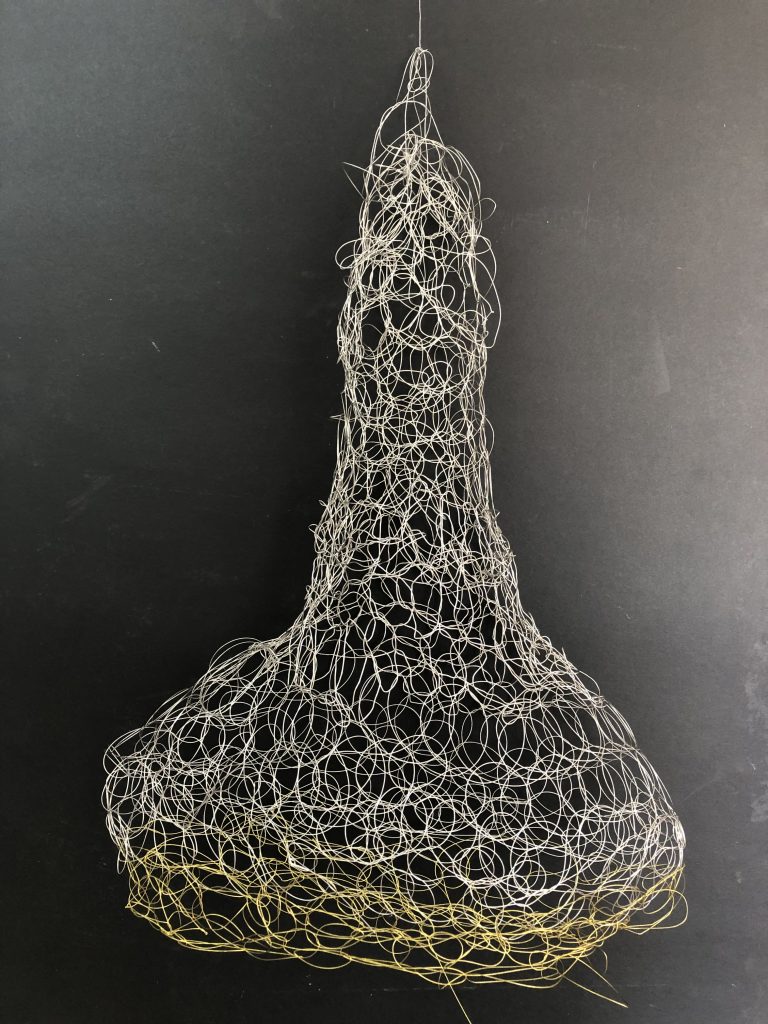

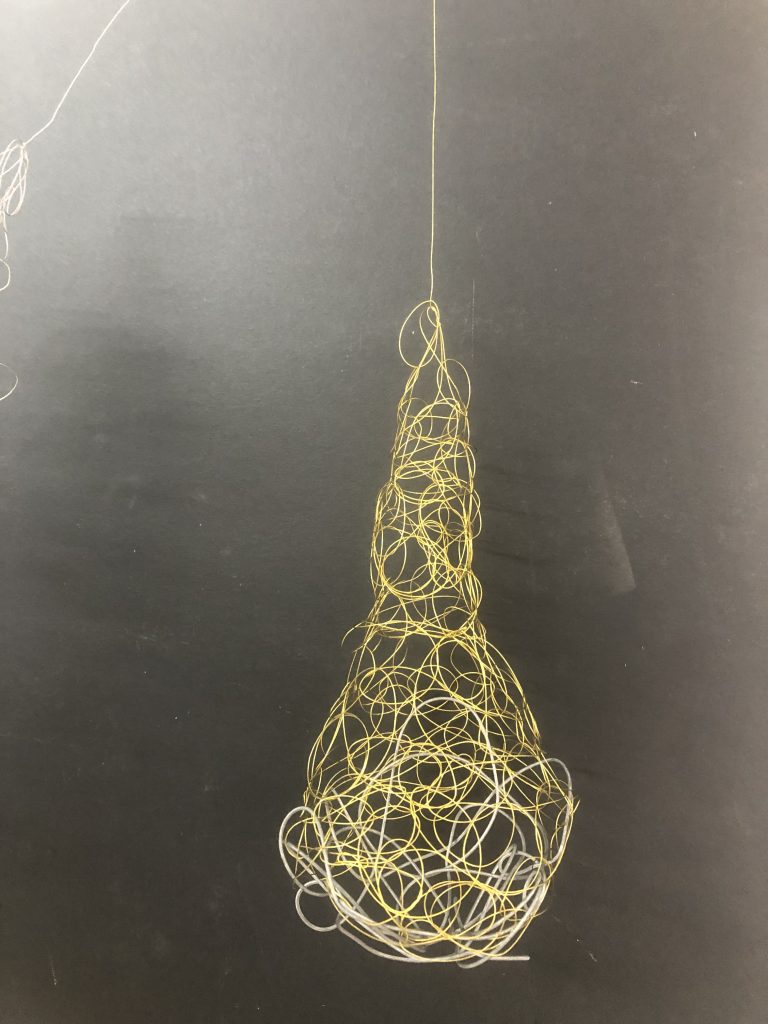

I feel a breakthrough in my making happened when I applied the use of soft wire onto an object I was weaving with raffia and jute (see image 4.) and asked if I could remove the jute around which I was looping with wire and still have a form left behind. I am happy with this outcome, as it is the first attempt. The jute as material in this making looks like it became a tool to hold the loops in place, but it also shows how different materials work together in this exploration. In this case, I would say the form reminds me of cocoons, which reminds me of a nest again. This new form is more collapsible and does better as a hanging installation. (Fig.7-9)It reminds me of Asawa’s work, which has strongly influenced this exploration. I also made a small drawing as the shadows from the object became another layer to consider.

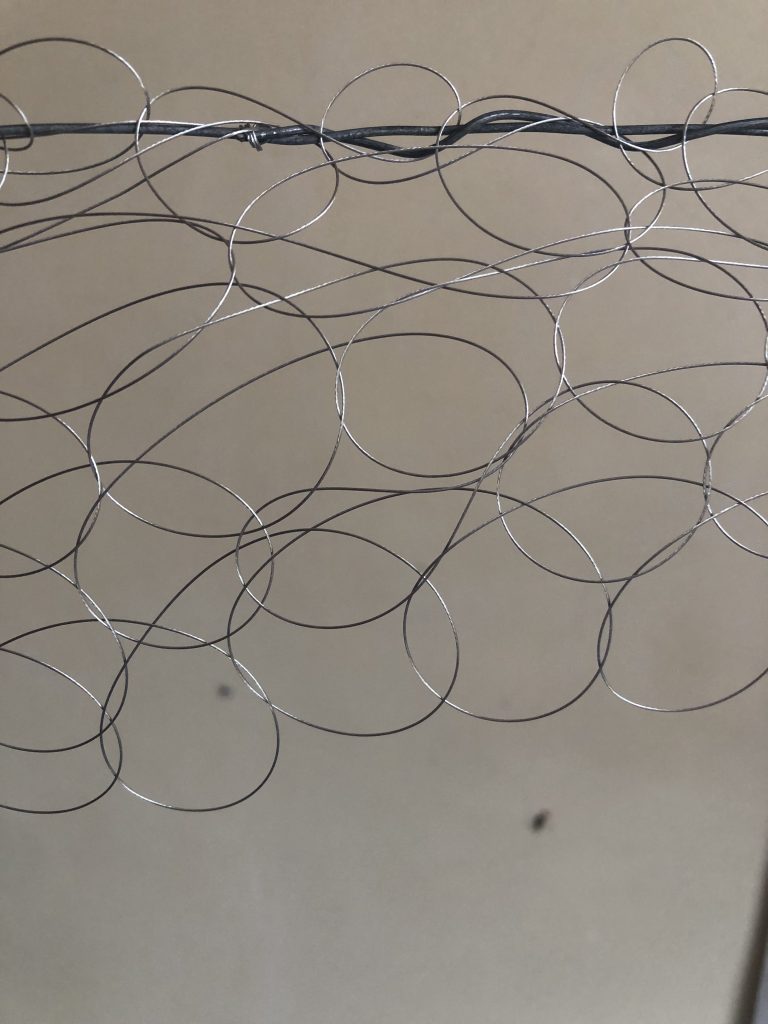

In the next few days I thought of images where I saw Asawa at work; her works were already hanging as she made them. Was it to compensate for this floppiness? She often worked backwards: first exploring a medium’s natural potential or inclination and then allocating a subject matter accordingly. Does this imply that her method showcases her technical prowess and highlights her ability to let the chosen medium guide and inspire the creative journey? One could think so as the result of her body of work is that is not constrained by preconceived notions but instead celebrates the inherent potential of artistic materials. It also makes me think about how intuitive or playful methods can lead to unexpected and innovative outcomes, but I cannot but admire her technical mastery and keen interest in the aesthetic possibilities of the medium she chose. To continue working with wire, I need to refine the looping technique and learn how to join my looping wire seamlessly. I became quite sure from watching this artist, that she works from a role of wire. I want to explore other wires as the current wire I work with, breaks easily. In image no 7, one can see the breakages during the looping process. I later worked with thicker steel wire where holding/keeping form intact is not an issue – see Fig. 6 above.

As part of reflective writing for my Research part, at the end of the course, I wrote the following as part of my ‘self evaluation : “Although I enjoy reading Tim Ingold, I wanted to move away from “anthropocentric” and “independent” as they convey that humans perceive themselves as separate or detached from life’s ecological and interconnected web. Human exceptionalism is a perspective that sees humans as distinct and superior to other species, often leading to a sense of autonomy and separateness. However, when I read “On Weaving a Basket”, I think his perspective opened up space for considering how non-human entities contribute to shaping skills and practices, challenging a purely anthropocentric view. Ideas of ‘dwelling in the world’ resonate with my practice, and I would like to explore these ideas further in terms of how they could link with art making. In an article, Drawing Together (2011: 220 -226), Ingold explores the idea of lines as threads of life connecting entities. These lines are not confined to human actions but extend to non-human entities. For instance, he discusses the lines that birds follow in the sky, emphasizing a shared world of movement and coexistence. I found his ideas around making as a kind of weaving and that as a skill, it helps to generate form, and I would like to explore this further (Ingold, 2000) in the last part of my studies (SYP). ” I do feel that, in a way, I used weaving to add to a layer of reading my research, but weaving became a process of making as well. (https://karenstandertart.co.za/research-part-five-endings-and-beginnings/.)

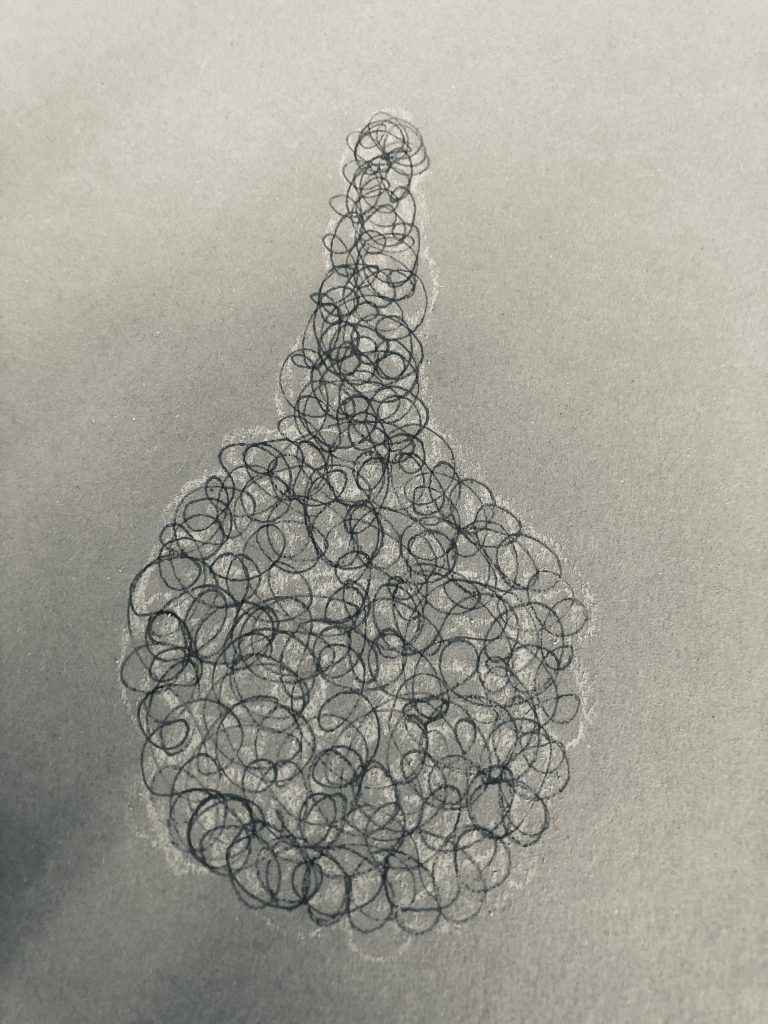

I explored a drawing with loops on the printed work I did on watercolour paper. (See Fig. 10 for the imprint of this work.)

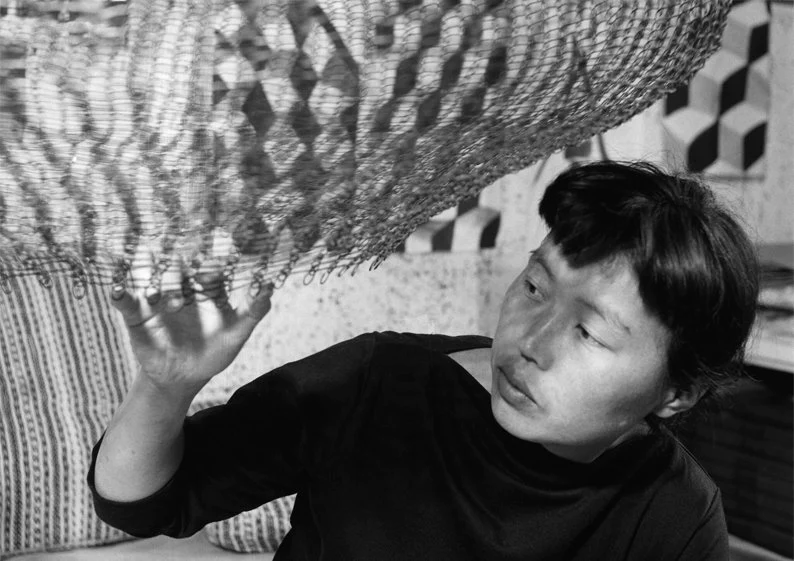

A day or so of more explorations brought some breakthroughs in my technical skills. I found a way to make a loop after contemplating the positions of the work of Asawa in images where she was busy weaving – mostly hanging. In the picture below, (Fig. 16) which belongs to the estate of Asawa, it is stated that Asawa was amazed by the simplicity of the wire loops that formed crocheted baskets and saw potential in these loops for her practice. Loops infiltrated almost every aspect of her work, and she viewed it as a fantastic technique.

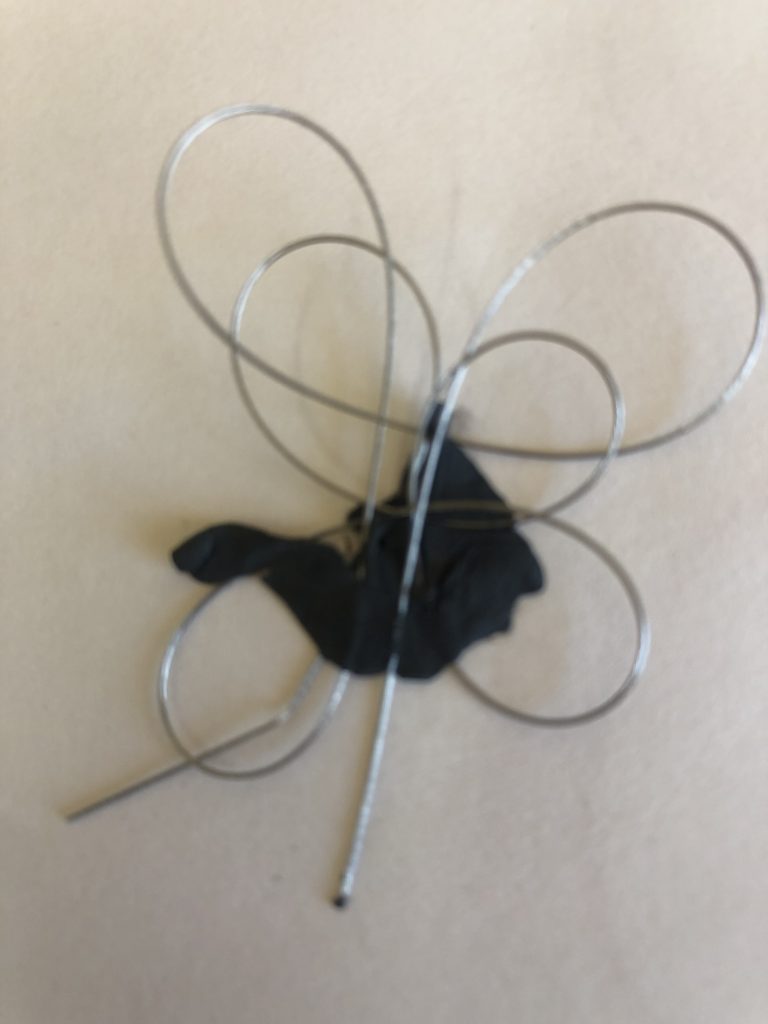

When I researched the looping technique, it was clear that Asawa understood how to exploit the flexibility of wire whilst also shaping it into refined loops that give her sculptures a porous appearance. The loops of wire join and contract while simultaneously retaining their physical form. This technique, however, is exceptionally fiddly; there is a rhythm I have to find, and I might give up on these attempts (Image 10) and be contemptuous of ‘wonky’ or ‘uneven’ work, or leave the fibre/raffia in the work. Other suggestions in a small crit group with fellow students are to combine the looping with stitching or knotting and try to form wavy lines with the wire and then connect it with raffia or wire or to work with a crochet hook….or give up on the wire and explore paper yarn more.

The following is quoted directly from the Toast Magazine website:..” she said, the shape comes out working with the wire…you work as you go along…you make the line, then you go into space…it’s a like a drawing in space.”(Hoefer,2006) I find that my technique works in the same way: I took a single line of wire thread (a single piece of material ?) and created a three-dimensional object from that one continuous line. It reminds me of drawing.

I used thicker wire to create a hoop and started weaving directly around it with loops. I use my fingers as I work with wire on a roll. It becomes a continuous process of working through the next loop as I go around the circular form and repeat the process with every loop. In figure 21 one can see that I used two different weaving materials. I can report that the second material, the Resin Core Wire of 0.71mm, does not give the desired looping outcome; the material too quickly loses form and is not easy to weave. (see fig. 21) I later removed the wire hoop onto which I started the looping, and I do like the outcome of the object and see the potential to continue looping with the material. I know that this is not the method Asawa used.

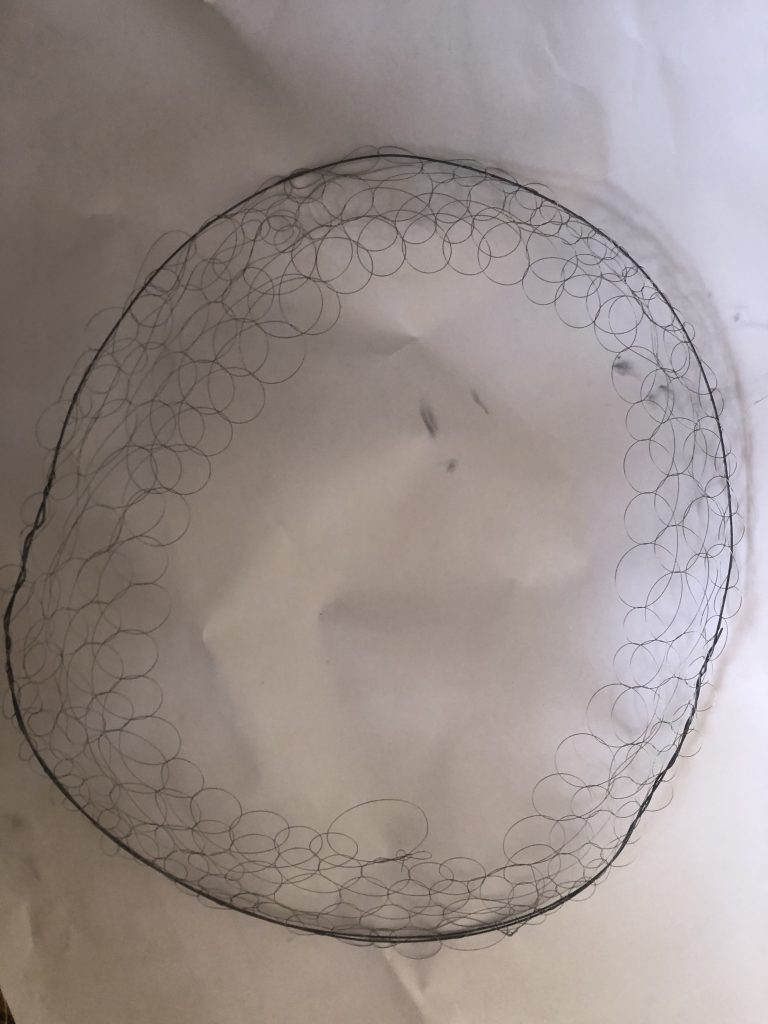

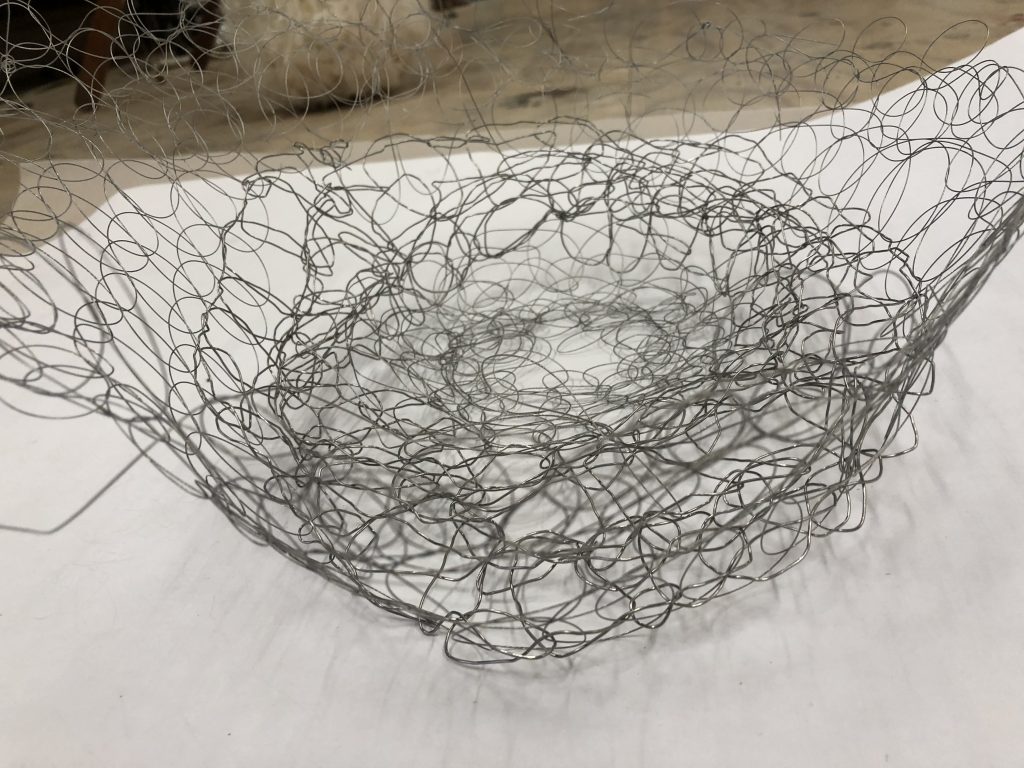

I look at these works a rough experiments, but think I can now work at mastering the process of looping with a continuous wire and focus on the aesthetic outcomes. Below as Fig 23 is a floppy bowl formed by the above looped wire exploration, after I removed the wire to create the hoop at the start of looping. Looking at the floppyness of this work, I thought about the almost vulnerability of this work – could say it has a temporary nature. But this could cause that one overlooks the robust and enduring qualities that exist within the actual physical construction. In the Courtauld article, Chalabay refers to Ruth Asawa’s use of repetition in her artwork aimed to convey a sense of the infinite. She then use an example of Briony Fer who suggested that this theme is a broader trend in art and that it persists beyond the modernist era, where structures of repetition are explored in connection to the experience of infinity. When I read this I decided to continue with the copper wire I had – but this time I started where I originally started the work – working back into the work and expanding it from that side. By now I had two sets of looping in the work – from the ‘bottom’ and at the ‘top’. (See figures 24 and 25)

Working with two strands of wire into the work – considering infinity. I then ended the top part of the hanging object but continued to explore infinity by picking up where I initially started with the gold-coloured wire.

This work is hanging as I work with the copper Tiget tail thread. The image, taken against a dark background, makes the object more visible.

A comment on an image of the detailed view of the looping (see Fig. 24) led to a discussion to compare the work with Cy Twombly’s paintings. It took me to the line used in the work, both as material and the technique (loop reminds of the letter e). I thought that the process and work are about the act of the hand in the work and the hand at work. Does the looping show a tension between the gesture of writing (e loop) and the rhythm of the weaving technique? On viewing the object, one’s brain can see the continuous writing of the e in the form. Here, the gesture of looping as a line created a shape also recognizable as a nest, cocoon, or seed.

I explored more making with the different wires and found the softer wire more manageable to work with – loops are more controlled and give the effect of sameness and repetition.

I know that placing the work in groups and or in large spaces and using the shadows they cast on nearby walls can be a very effective way to share it.

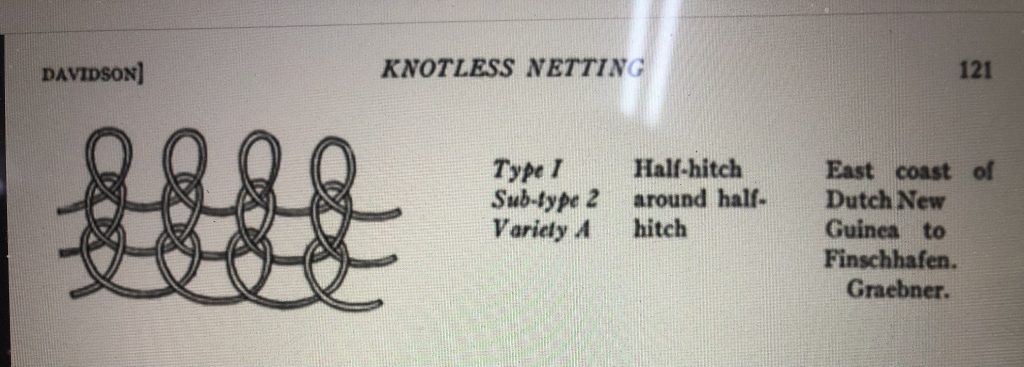

As I continued exploring methods for looping, I found more clues in Ruth Asawa’s work to confirm that her wire was coiled on a dowel; most probably, this ‘spiral’ was then flattened. It looks like a line of e-shapes repeating in cursive writing. She probably started the looping process by ‘clicking’ or pushing the e-loops into the next row of e-loops. (slots into the prior loop) I discussed this with my crit group, and students from the Textiles group confirmed this fiddly work process. One student shared her attempt. I am grateful the research led to a method being learned and the prospect of new making to emerge from this learning.

I have done eight rows connecting the e-loops to a previous one in the above work. The process reminds me of drawing and knitting, and it is time-consuming and laborious on my hands.

Reflecting on this making (more thinking about my journey in this course)

The notion of playing with presence resonated strongly with me as I delved into Ruth Asawa’s works. Exploring the possibilities of wire—turning it inside out, working from the inside out, and engaging with shadows as a transitional space—unveiled intriguing dimensions. Like the intermediary stage between objects and flat drawings, shadows prompted me to contemplate further. Intrigued by the idea, I experimented with printing the woven work on a gel plate, though not entirely successful (see image 9).

My curiosity led me to explore transparency in making, drawing inspiration from artists like Asawa and Falkenstein. I appreciated the feedback from a critique group that encouraged thinking beyond conventional tools—“knitting without needles and weaving without a loom,” akin to Asawa’s distinctive approach.

The looping technique, central to Asawa’s work, proved intricate. Finding a rhythm became crucial, yet the fiddliness posed challenges. Suggestions from fellow students opened avenues for exploration, including combining looping with stitching or knotting, creating wavy lines with wire, and experimenting with paper yarn.

For me, weaving became a reflective practice, a dialogue with materials and the act itself. This intentional approach deepened my interest into the craft and its expressive potential. I think it is important not to deny the relationship between weaving and function, but I had discovered another way/process to have a dialog about materiality, conceptualism and the boundaries of art as process of making.

As I find myself at the intersection of drawing and weaving, questions arise about the intent of my work. Does it lead to a deeper integration of techniques or blur boundaries between mediums? The course has propelled me to keep exploring, revealing that the process becomes a means to express intentions. Is this intellectual, practical, or a blend of both? Drawing, often seen as an internal dialogue, shares similarities with my weaving experience.

After a critique of my making, I was recommended to read Susan Sontag’s essay “Against Interpretation” (1966). The excerpts about transparency, recovering our senses, and the role of criticism resonate with my current exploration. Looking at this making with wire thread and about Susan Sontag’s essay, I ask myself if exploring transparency further adds depth to this material inquiry. Transparency, as Sontag describes it, involves experiencing the luminousness of things in themselves and cutting back content to see the essence of the artwork. (See fig. 25)

Contemplating potential historical links between traditional female roles and my exploration of nests raises questions about feminism and societal hierarchies. Contextually, my work delves into narratives of loss, repair, care, interconnectedness, deconstruction, and place. Originating from a personal need for healing and connection, creating large-scale nests or cocoon-like objects is a therapeutic engagement with materials. A friend shared an article (Arch Daily, online version) about the traditional building of huts in African cultures, which made me think about how weaving becomes a means to shape and structure materials, contributing to the overall sensory and perceptual experience for both the artist and the viewer. It talks about how artists dialogue with the materials and the medium, fostering a reflective practice that deepens their understanding of the craft and its expressive potential.

My artistic journey becomes a way to navigate connections, raising questions about their permanence and contributing to a deeper understanding of hidden narratives within nests, families, homes, and communities. The weaving process is something to consider as it connects the artist with their designs. This connection can imply a personal and intimate relationship with the woven creations, where the artist’s intentions and emotions are woven into the fabric. I also like the idea that a viewer can be within the space of these objects when they are hung from the ceiling as installations. The experience becomes more participative.

I wonder if I should look into the historical link between traditional female roles in the domestic part of (so many) cultures and/or if these objects and nests are part of my feminism ‘ideology’ and search for an understanding of societal hierarchies. I would argue that I am contextually exploring narratives of loss, repair, care, interconnectedness, deconstruction, and place. On a personal level, it originated from loss – a re-visit and healing process of what connections are hidden in a nest/family/home/group/community. By making large-scale nests or cocoon-like objects, my body can engage with the material and allow my healing process. I look at my process as a way to make connections. Whether they are permanent is a question I had to deal with.

List of illustrations

Fig. 1 Mac, Wendy. (2022) Asawa inspired doodle. [Photograph] Postcast illustration. At:https://club.drawtogether.studio/p/12-drawing-in-the-air-with-ruth-asawa#details. (Accessed 06/01/2024).

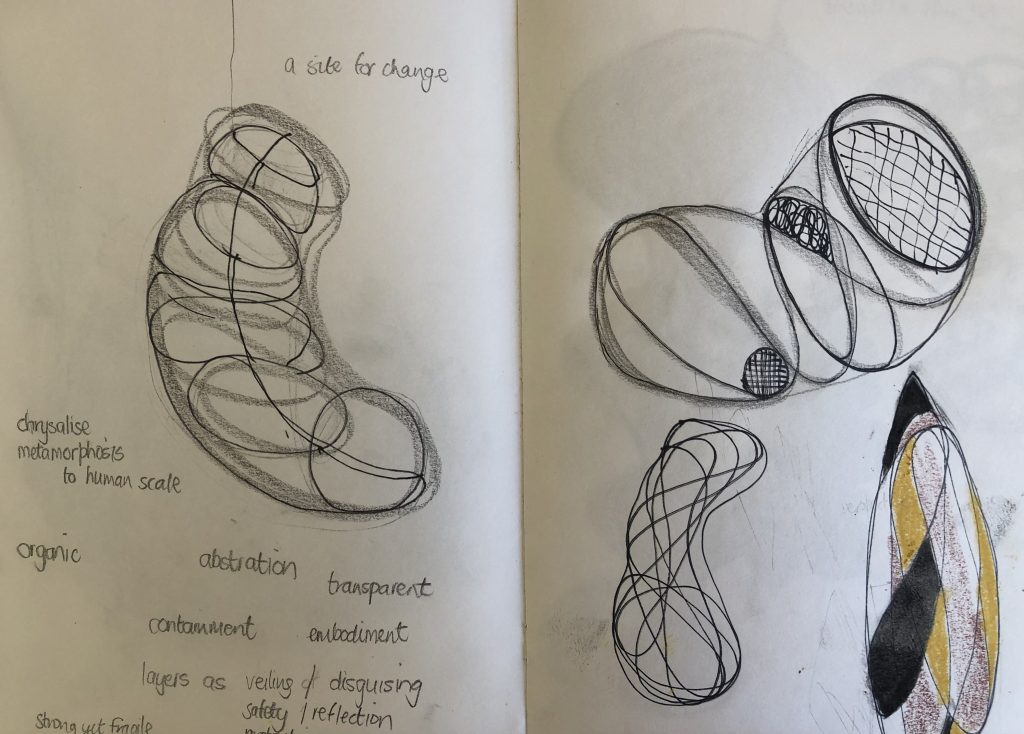

Fig. 2 – Fig 4 Stander, K. (2024) Sketchbook doodles. [Photographs of charcoal drawings] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 3 Stander, K. (2024) Sketchbook doodles. [Photographs of charcoal drawings] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 4 Stander, K. (2024) Sketchbook doodles. [Photographs of charcoal drawings] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 5 Stander, K. (2024) Woven object with wire looping. [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 6. Stander, K. (2024) Looping with raffia and wire. [Photograph] In possession of: the author:Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 7 Stander, K. (2024) Wire looped container. [Photograph] In possession of: the author:Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 8 Stander, K. (2024) Sketcbook drawing. [Photograph] In possession of: the author:Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 9 Stander, K. (2024) Sketchbook exploration with wire container. [Photograph] In possession of: the author:Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 10 Stander, K. (2024) Imprint in sketchbook. [Photograph] In possession of: the author:Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 11 Stander, K. (2024) Material explorations of the loop. [Photograph in sketchbook] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 12 Stander, K. (2024) Soft wire loop in a sketchbook. [Photograph in sketchbook] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 13 Stander, K. (2024) Loop drawings [Photograph in sketchbook] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 14 Stander, K. (2024) More sketchbook doodles. [Photograph in sketchbook] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 15 Stander, K. (2024) Strings of e-loops. [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 16 Cunningham, Imogen. (1957) Ruth Asawa at work [Photograph and the artwork belongs to the estate of Asawa] At: https://www.toa.st/blogs/magazine/ruth-asawa-life-works (Accessed 08/01/2024).

Fig. 17 -22 Stander, K. (2024) WIP [Photograps sharing the making of a vessel. The work is still incomplete] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 23 Stander, K. (2024) Loopy vessel 1 [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 24 Stander, K. (2024) Loopy vessel 1 [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 25 Stander, K. (2024) Loopy Whimsey Vessel [Photograph as it hangs in front of a black background] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 26 Stander, K. (2024) Small and Whimsey [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 27 Stander, K. (2024) Sketchbook drawing [Photograph with charcoal and soft pastel on Fabriano with filter] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 28. Stander, K. (2024) Skecthbook drawing [Photograph with charcoal and soft pastel on Fabriano] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Fig. 29 Asawa, R. (1958) Untitled (S.089) [Photograph] Online At: https://www.frieze.com/article/ruth-asawas-shadow-play (Accessed on 16/01/2024)

Fig. 30 Stander, K. (2024) Looping with wire [Photograph of a work in progress] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeek West.

Bibliography

Chalaby, Cora. (2021) ‘The Immateriality of Materiality: Ruth Asawa’s Looped Wire Sculpture’. Online At: https://courtauld.ac.uk/research/research-resources/publications/immeditations-postgraduate-journal/immediations-online/immediations-no-18-2021/the-immateriality-of-materiality-ruth-asawas-looped-wire-sculpture/#:~:text=Asawa’s%20process%20of%20looping%20wire,and%20invisibility%2C%20absence%20and%20presence. (Accessed on 05/01/2024).

Giachino, Michela. (2022) ‘Falling in Love with Ruth Asawa’ In: The Oxford Blue 06/06/2022 At: https://theoxfordblue.co.uk/falling-in-love-with-ruth-asawa-exhibition/#google_vignette (Accessed 14/01/2023).

Hoefer, Jacqueline. (2006) ‘Ruth Asawa: A Working Life, The Sculpture of Ruth Asawa’. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and University of California Press: Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2006, p. 17. This quote was shared by Toast Magazine on 24 October 2017.

Ingold, Tim. (2000) Making culture and weaving the world Whitechapel Gallery, London. p 164 -165

Luther, Elaine. (2019) ‘Ruth Asawa and the Mythical Basketmaker of Mexico”. In: Blogpost 09/09/2019. At: https://www.elainelutherart.com/ruth-asawa-and-the-mythical-basketmaker-of-mexico/ (Accessed 11/01/2024).

Reynolds, Anne. (2018) ‘Ruth Asawa’s Shadow Play ‘ At: https://www.frieze.com/article/ruth-asawas-shadow-play (Accessed 11/01/2024).

Smarthistory ( ) ‘Ruth Asawa Untitled’ Online video At: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pv4WGBgVZ-c

Sontag, Susan (1966). Against Interpretation. pdf