Ideas to develop

Light into my wire nests and objects

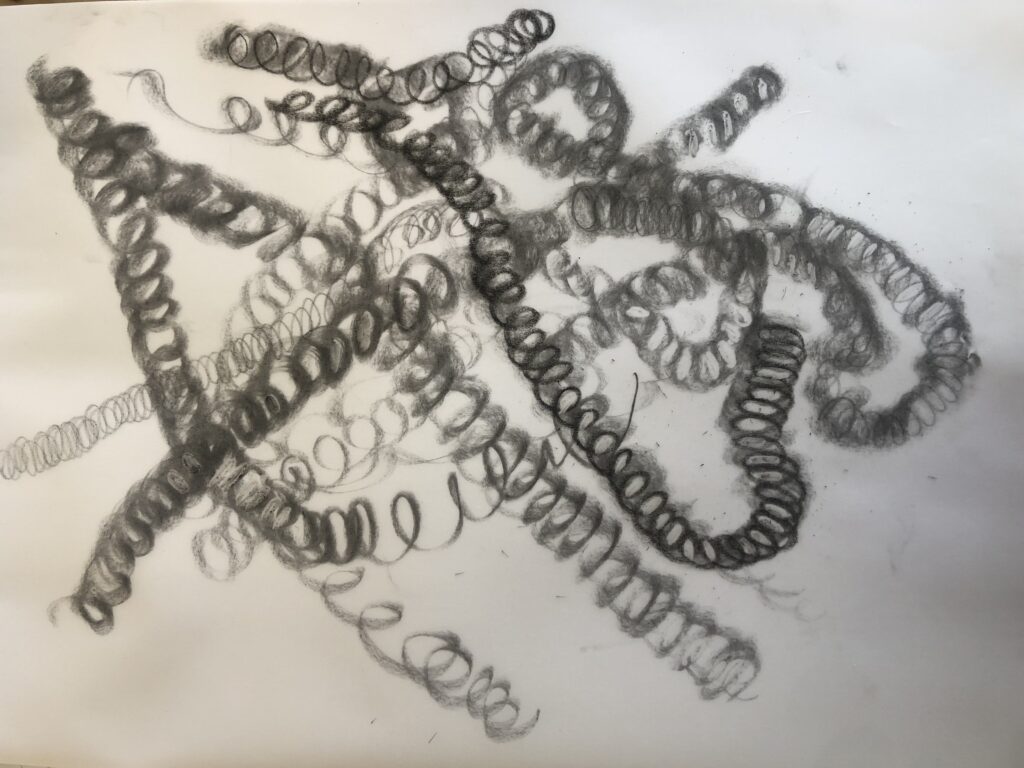

Inspired by Ruth Asawa’s work, I’m bringing the idea of air into my wire nests to add to the conceptual framework of my work and discussions. The nests’ construction, with open loops that allow air to pass through, can enhance this interaction, making the movement of air a visible participant in the piece. During the exhibition, I want to focus on how light and shadow play across the surfaces of the nests. As light passes through the openings in the wire, intricate patterns of shadow can emerge and change throughout the day, turning air and light into active elements of the sculpture. I want to consider how my sculptures might subtly interact with air currents, creating a dynamic, living quality. I am more an more drawn to the idea of the material being solid, but the work being airy and transparent. This approach enhances the physical presence of the nests and invites viewers to engage with the invisible forces that give them life, creating a deeper connection between my work and the natural world.

I can now add the rest of my wire objects to the exhibition and by emphasizing these aspects, the work can evoke a delicate balance between the material and the immaterial, much like Asawa’s pieces, where air, light, and shadow are as integral as the wire. I plan to suspend groups of sculptures from the ceiling and hope this becomes cohesive installations or hybrid structures between sculpture and installation, and can be seen as works separate from the nests. I looked at a David Zwirner Gallery installation where Asawa’s sculptures are suspended from the ceiling. It hung at various heights, and were positioned adjacent to and in front of one another. As a result, the viewer can look up, around and through the sculptural grouping.

The Nest versus a Cage

I do think this is an idea to develop my contemporary art pieces. When I worked on the concept of the sociable weaver nests found on old telephone poles, I encountered many of these on the roads in the Northern Cape where these birds congregate. Below is a nest I made, referring to the nests on telephone poles.

The nest lying on the floor before I added the ‘chambers’ reminded me of fish traps I have seen, thus taking me to nests as cages and how, over time, the concept has different meanings. This duality reflects the complexity of spaces in our world—spaces that can be protective and confining.

Interesting that in my research into the work of Ruth Asawa I came upon a Courtauld article, The Immateriality of Materiality: Ruth Asawa’s Looped Wire: Her work, Untitled (S.077), is discussed and stated as her innovative way that Asawa of using craft processes as a means of artistic experimentation. The writer of the article then refers to the origins of Asawa’s technique and her gendered and racialised artistic identity when she writes: ” were used by critics to denigrate her work as lacking innovation, contributing to Asawa’s marginalisation within art histories.[26] For example, in a 1955 review of Asawa’s work, Otis Gage stated, ‘the technique has its disadvantages … that relates these objects uncomfortably to baskets and fish traps …’.[27] Asawa’s sculptures, however, do not deny their genetic relationship to function but astutely invoke concurrent dialogue about materiality, conceptualism, the boundaries of craft and art, and the politics of process.”

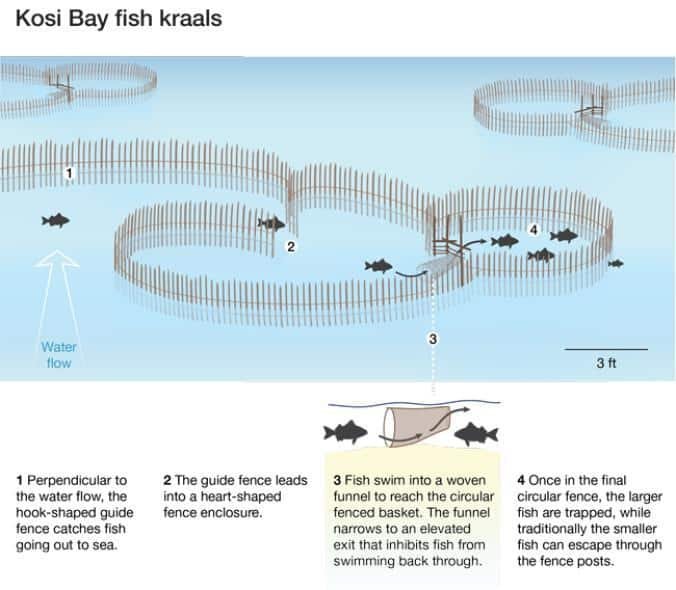

In northern South Africa, the Tsonga people fish sustainably with wooden fish traps constructed along a part of the Kosi Bay estuary. Unfortunately, things are changing, and the impact is increasing due to different fishing methods and attitudes towards sustainability that have changed towards being commercial. A discussion between a fisherman and a journalist gives a great story about the ‘positive’ use of a ‘trap’. “I asked Mkhonto why he fished with a trap and not with a more efficient method, such as a gill net. With a trap, he said, you catch one fish, or two, or three. With a net, you might catch 10, 20, 50. Not good for me,” he said, including himself in the sustainability equation. (https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/141114-kosi-bay-south-africa-fish-traps)

Along the South Western coast of South Africa, I know of ‘tidal’ fish traps, which are seen as ancient intertidal stonewalls alongside the coastline. The ones, alongside the town of Stilbaai, are still working relics from the past. Most of these traps that can still be seen were built during the past 300 years, while others could date as far back as 3,000 years ago.

I do consider materiality and process in my work and how as in the case of Asawa the woven objects, while functional, stays deeply rooted in cultural practices and craftsmanship. I think as an artist Asawa was consciously engaging with it in her work. By drawing on these forms she was recontextualizing them within the fine art world. She used the familiar language of craft to explore complex themes of materiality, space, and the relationship between the functional and the aesthetic. I read that her largest multi-lobed sculptures extend to twenty-one feet in length from top to bottom.

Reflecting on the dual nature of the nest in terms of safeguarding and confinement or imprisonment and protection, I have to consider the human-nature relationship. I am so aware of how human interventions, which are primarily well-intentioned, can lead to unintended consequences. It implies limiting the freedom and natural behaviour of the very creature(s) in nature we aim to protect. It reflects the paradox, showing how our desire to protect can isolate and constrain us. I also thought about the resilience and adaptability of nature – can the wire nest mirror something of this possibility for beauty and harmony?

Using other materials for a nest

After encountering corrugated cardboard by artist Anna Hepler, I want to consider using cardboard. The use of light and shadow through the material, as well as it being a way to ‘build’ captured my attention. I sourced a supplier from which I can buy bulk rolls as they are used in the packaging industry. My thoughts are leaning more toward sourcing material as an upcycling process of making. This process is time-consuming, and the nest will take longer to construct. There is the possibility of a community project to gather materials.

Look at this article: https://birds4africa.org/weaver-research/weavers/783a/

Open nests evolved from closed nests in ancient passerines. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=62G9kw9Ziek

little engineers

colossal structure

Planning and writing about the exhibition and Body of Work

I added this part of the blog on Monday 09/09/2024, after considering advice from my tutor with regards to the learning outcome: Demonstrate an understanding of the professional context that your practice is

situated in and identify strategies for sustaining your practice. I wanted to bring in some wider references and look at exhibitions, the hanging style and the decisions made.

I re-read Gilda Williams’ How to Write About Contemporary Art during our two-week trip to Namibia. I was inspired to combine accessible language and emotional depth and clearly describe my work’s themes. The text should appeal to both general audiences and those familiar with contemporary art. I have to create a bridge between my narrative and the larger context of my work. I am comfortable keeping the ‘abstract word count’ low and being more ‘me’ in this writing.

When I considered writing about a specific work like Kalahari Hotel 2024, I was forced to consider what is ‘special’ about my work and how to entice viewers in straightforward language to believe that visiting this exhibition will be worth their while.

I wrote the following about the wire nest I call Kalahari Hotel 2024 to share with a few people before I make final decisions about printing/marketing.

Dear xxxx, please read my thoughts for a short promotional piece or a catalogue/text/marketing for my upcoming exhibition of my BOW for my studies. Consider whether I have covered what it is, what it might mean, and how it connects to the world at large.

Version One

The Kalahari region in Southern Africa is an arid home for everyone. I set out to bring a personal story of motherhood, care, family, loss, and community together under a big, in my mind’s eye, camelthorn tree. For thousands of years, little birds called sociable weavers have been building their compound community nests in this tree. In nature, these nests are not only occupied by the sociable weavers; a long list of other bird species and other small animals also use them for roosting, breeding or protection from predators. They remind me of giant apartment blocks that can be occupied for over 100 years. This is a perfect example of how socialistic behaviour and the strategy of building thermal shelters can overcome the harsh desert environment.

In Kalahari Hotel 2024, the wire nest symbolizes more than shelter or communal living. The wire embodies the tension between protection and imprisonment, echoing humanity’s complicated relationship with the natural world. Our efforts to enclose, protect, or conserve nature often reflect our desire for control, creating barriers that serve human interests more than nature’s intrinsic needs. The delicate and confining nest invites viewers to reflect on the thin line between safeguarding and restricting and how our actions can disconnect us from the natural world we claim to protect.

Rather than directly replicate, I borrowed from the ingenious skill of these birds to create my suspended lump of wire with an airy and transparent view of the inside. Making the nest with wire was long and repetitive, leaving much time for weaving my personal story.

OR Version Two:

In 1779, the first person to describe these vast nests, Paterson, compared them to thatched roofs, calling them ‘aerial cities.’ This image resonates deeply with my work, as my wire nests mirror the form of these vast, communal structures and the human desire to build, protect, and shelter. As a home/hotel to hundreds of birds, it reflects the complexities of social cooperation and the delicate tension between confinement and community. They embody the shared space between humans and nature, cooperation between species, and the interconnectedness of life.

Just as the Sociable Weavers build their nests through cooperative effort, with kin-directed relationships shaping the structure, my wire nests reflect the importance of community and collaboration. These nests are not just physical shelters, but spaces that symbolise the shared efforts of nature and humanity to create homes, support systems, and interconnected lives.”

or a Combined idea:

In 1779, the explorer William Paterson described the vast nests of the Sociable Weaver as “aerial cities,” comparing them to thatched roofs suspended high in camelthorn trees. These communal structures, which house hundreds of birds and other species, have inspired me to create wire nests—spaces that mirror the complexities of shelter, protection, and cooperation.

My work, Kalahari Hotel, weaves together my personal story of motherhood, care, family, and loss. Just as the weavers build these intricate nests as a shared effort, I contemplate my need for a safe space while reflecting on the delicate balance between protection and constraint. You encounter a suspended lump of wire hanging from the trusses, and on a closer look at the underside, it is unexpectedly filled with smaller nests. You feel like looking through the nest.

These nests, like hotels in the sky, are not just homes for the weavers but also sanctuaries for various other species, exemplifying how social cooperation can overcome harsh environments. I consider our disconnection with nature. Our protective instincts, embodied by wire, often separate us from the environments we seek to preserve. By creating barriers, we exclude ourselves from the experience of nature’s raw, unmediated beauty and complexity.

Crafting these wire nests was long and repetitive, much like the weavers’ laborious construction and maintenance. This allowed me to intertwine my narrative with the nests’ symbolic meaning. Through this work, I aim to highlight the interconnectedness of life—between humans and nature—and the need to create spaces of care and connection.

Making use of photographs

Presentation and clarity are needed. I have asked professional photographer friends to assist and share ‘tomorrow’s’ news. Up to now, I have not shared many images of the wire nests on social media. I have mostly played with the idea of transparency, light and shadow casts. How the surrounding space became an integral part – somehow, this plays with the concept of boundaries, the wire being a material associated with constraint or a barrier and my inquisitive nature to know how it looks inside the nest.