Planning and writing about the exhibition and Body of Work

I re-read Gilda Williams’ How to Write About Contemporary Art. I was inspired to combine accessible language and emotional depth and clearly describe my work’s themes. The text should appeal to both general audiences and those familiar with contemporary art. It is essential to create a bridge between my narrative and the larger context of my work. I am comfortable keeping the ‘abstract word count’ low and being more ‘me’ in this writing.

I added this blog on Monday, 09/09/2024, after considering advice from my tutor regarding the learning outcome: “Demonstrate an understanding of the professional context in which your practice is situated and identify strategies for sustaining your practice. ” I want to incorporate broader references, examine exhibitions, consider a hanging style, and the decisions made.

When I considered writing about a specific work like Kalahari Hotel 2024, I was forced to consider what is ‘special’ about my work and how to entice viewers in straightforward language to believe that visiting this exhibition will be worth their while.

I am excited about using the farmyard as an exhibition space. I will encourage the audience to walk between the nests, the barn, and the outdoors, inviting them to experience the boundaries (or lack thereof) between these spaces. I hope this space will create a dynamic interaction where they are not just viewers but participants, exploring how the shed and the artwork engage with the natural world. I want to allow parts of the exhibit to be altered by natural forces, emphasizing the temporary and evolving nature of the space—just as the meaning of spaces changes over time based on their use and the people who inhabit them. (I finally decided to use the hay on the floors and have drawings on the floors, between the hay) My tutor commented on our last tutorial regarding the space: ‘Change the context and watch how meaning shifts’.

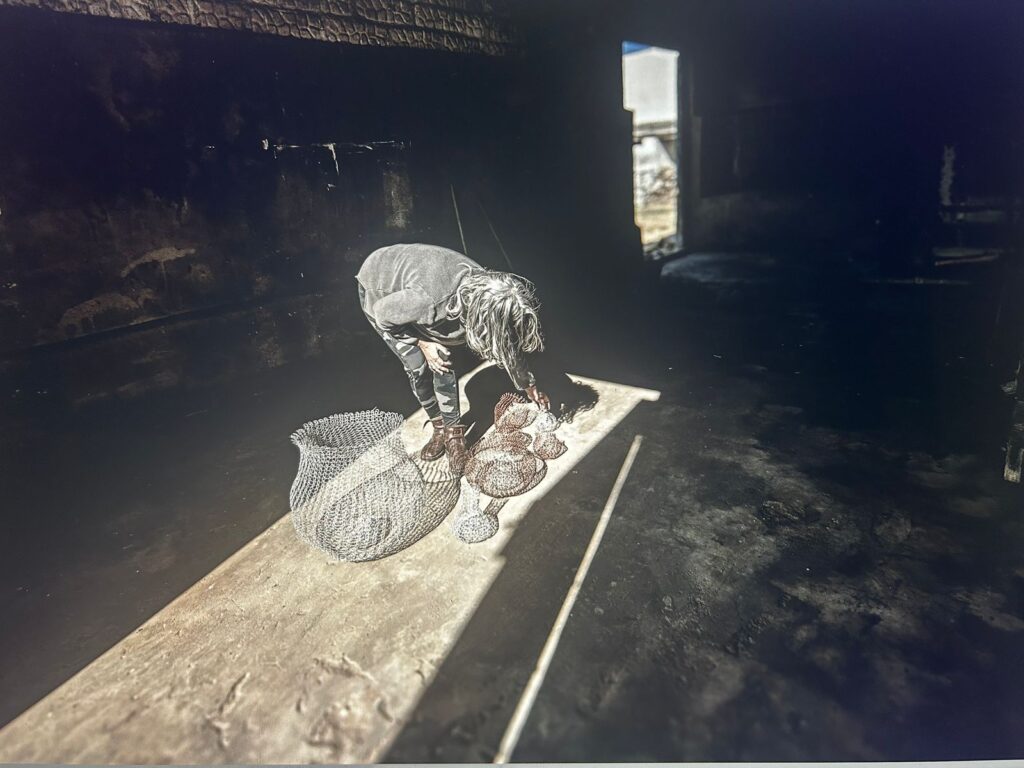

After weeks of preparing the space, I moved the work into it and started working there. I was inspired by the natural surroundings, including the birdsong and vague sounds of farmyard happenings, like the ‘blare’ of a sheep or a tractor driving somewhere. It was very different from my studio, where I was constantly confronted by being in our home, looking at the little garden that asked for my attention and the movement of farm equipment and staff when I opened my doors. By working in this space, which, in my mind, was also going to become a ‘gallery’, I enjoyed the experience of questioning what a gallery is and how my work will interact with viewers in this space. In my study material, I had to research the ‘critical framework’, and my vulnerabilities towards how the work will be received had to be addressed in such a task – this was the ideal space to go through these very fragile thoughts, which sometimes can be described as fearful and unsure. I considered my material as a ‘farm’ material – fences utilise the wire. I was assisted by a farm worker, who is in charge of maintaining fences around the sheep kraals.

Other practical things

When thinking of the use of photographs, presentation and clarity are needed. I have asked professional photographer friends to assist and share ‘tomorrow’s’ news. Up to now, I have not shared many images of the wire nests on social media. I have mostly played with the idea of transparency, light and shadow casts in my shared visuals. I talked about how the surrounding space became an integral part. Somehow, this plays with the concept of boundaries, the wire being a material associated with constraint or a barrier and my inquisitive nature to know how it looks inside the nest.

Considering the use of a barn, I want to intentionally leave parts of it open to the elements or highlight its worn, exposed structure to show that the barn, like the nests, is part of a larger ecosystem. In this way, the ‘gallery space’ reflects ideas about the relationship between humans and nature—connected and separated by the structures we build. It taught me how to think anew about boundaries between species and human and non-human relations.

I envision something as follows to build on for a press release (even if I do not intend to publicise it)

“Kalahari Hotel will not be housed in a traditional gallery; it exists in a space that once served as a shelter for tools, work and haybales —an echo of the rugged landscape of the Kalahari Desert, where sociable weavers build their nests. This shed becomes a place where human history and nature collide, mirroring the themes of community, protection, and isolation woven into the wire nests. As you enter the space, you are stepping into a structure that has changed its meaning, much like the nests. The walls that once kept the outside world at bay now invite you to reflect on the boundaries we create between ourselves and nature, and what it means to feel safe and connected.”

I wrote the following about the wire nest I call Hotel Kalahari 2024 to share with a few people before I make final decisions about printing/marketing.

Dear xxxx, please read my thoughts for a short promotional piece or a catalogue/text/marketing for my upcoming exhibition of my BOW for my studies. Consider whether I have covered what it is, what it might mean, and how it connects to the world at large.

(view at: https://karenstanderart.co.za/kalahari-hotel-2024/ )

Version One

The Kalahari region in Southern Africa is an arid home for everyone. I set out to bring a personal story of motherhood, care, family, loss, and community together under a big, in my mind’s eye, camelthorn tree. Little birds called sociable weavers have been building their compound community nests in this tree for thousands of years. In nature, these nests are not only occupied by the sociable weavers; a long list of other bird species and other small animals also use them for roosting, breeding or protection from predators. They remind me of giant apartment blocks that can be occupied for over 100 years. This is a perfect example of how socialistic behaviour and the strategy of building thermal shelters can overcome the harsh desert environment.

In Hotel Kalahari 2024, the wire nest symbolizes more than shelter or communal living. The wire embodies the tension between protection and imprisonment, echoing humanity’s complicated relationship with the natural world. Our efforts to enclose, protect, or conserve nature often reflect our desire for control, creating barriers that serve human interests more than nature’s intrinsic needs. The delicate and confining nest invites viewers to reflect on the thin line between safeguarding and restricting, and how our actions can disconnect us from the natural world, we claim to protect.

Rather than directly replicate, I borrowed from the ingenious skill of these birds to create my suspended lump of wire with an airy and transparent view of the inside. Making the nest with wire was time-consuming and repetitive, leaving much time for weaving my personal story. Viewers are invited to interact with the work. You can lie on your back, looking through the nest, or put on the headphones and consider being connected with the little engineers. Welcome to Hotel Kalahari!

OR Version Two:

In 1779, Paterson, the first person to describe the vast nests of sociable weaver birds, compared them to thatched roofs, calling them ‘aerial cities.’ This image resonates deeply with my work, as my wire nests mirror the form of these vast, communal structures and the human desire to build, protect, and shelter. As a home/hotel to hundreds of birds, it reflects the complexities of social cooperation and the delicate tension between confinement and community. They embody the shared space between humans and nature, cooperation between species, and the interconnectedness of life.

Just as the Sociable Weavers build their nests through cooperative effort, with kin-directed relationships shaping the structure, my wire nests reflect the importance of community and collaboration. These nests are not just physical shelters, but spaces that symbolise the shared efforts of nature and humanity to create homes, support systems, and interconnected lives.”

or Version Three:

In 1779, the explorer William Paterson described the vast nests of the Sociable Weaver as “aerial cities,” comparing them to thatched roofs suspended high in camelthorn trees. These communal structures, which house hundreds of birds and other species, have inspired me to create wire nests—spaces that mirror the complexities of shelter, protection, and cooperation.

My work, Kalahari Hotel, weaves my personal story of motherhood, care, family, and loss. Just as the weavers build these intricate nests as a shared effort, I contemplate my need for a safe space while reflecting on the delicate balance between protection and constraint. You encounter a suspended lump of wire hanging from the trusses, and on a closer look at the underside, it is unexpectedly filled with smaller nests. Viewers are invited to interact with the work. You can lie on your back and might feel like looking through the nest, or put on the headphones and consider that you have been connected with the little engineers who make these huge nests.

These nests, like hotels in the sky, are not just homes for the weavers but also sanctuaries for various species, exemplifying how social cooperation can overcome harsh environments. I consider our disconnection with nature. Our protective instincts, embodied by wire, often separate us from the environments we seek to preserve. By creating barriers, we exclude ourselves from the experience of nature’s raw, unmediated beauty and complexity.

Crafting these wire nests was long and repetitive, much like the weavers’ laborious construction and maintenance. This allowed me to intertwine my narrative with the nests’ symbolic meaning. Through this work, I aim to highlight the interconnectedness of life—between humans and nature—and the need to create spaces of care and connection.

PS (On 10/09/2024, I had more votes for version Three. Thank you to all who commented or contacted me via WA. I enjoyed the reaction and value your replies.

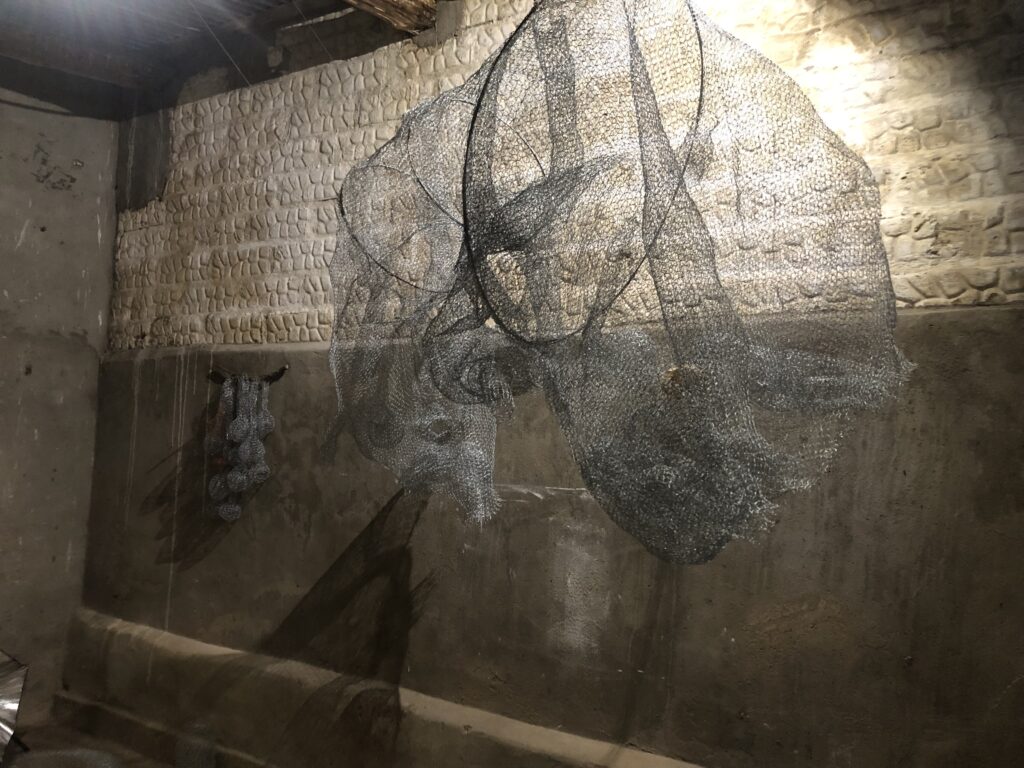

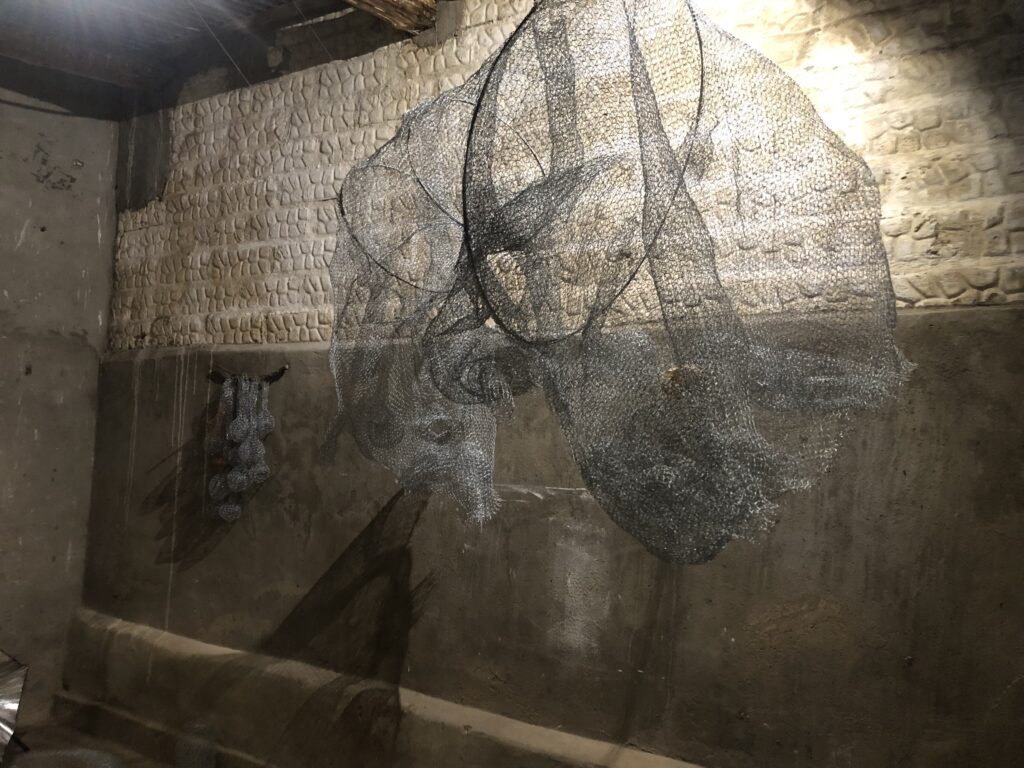

As the weeks until the opening started to feel like they were flying by, I had to focus on many other things—catering and marketing. The most challenging part of this project was how to use light. The more time I spent inside the space, the more convinced I became that evening was the most suitable time for these objects to show their magic. I love how volume is taken up in the space—the shadows become part of the work.

I was drawn to reading about Bill Viola’s journey to videography because I felt my lack of knowledge of photography and the use of light was becoming a primary constraint. I needed to understand my need for physical manipulation of space—I wanted the viewer to have this experience of being with a thing but also with its essence, the fact that the material allows light through it.

Below are inspiring images of work by Jaume Plensao, currently exhibited in Spain. The work is called Miralls at La Llotja and reflects upon present issues. It acts as a power unit, charging the space with light and darkness, opacity and transparency, past and future. His use of light and shadow inspired me.

I had to take time to reflect on light as I indicated it could affect the form of the work and create an experience for viewers. One can allow the viewer to see both the physical and intangible structures. I felt it would bring depth and emotional resonance into the work. As one walks around the nest and objects, you have a temporal experience as the shadows draft a second structure that is both there and not there.

This concept relates to Viola’s use of light, where elements seem almost otherworldly, extending the artwork’s reach into a more expansive, immersive experience. By directing light at specific angles or intensities, I might emphasize the work’s duality—the wire’s weight as a containment structure, contrasted by its permeability to light, suggesting openness or fragility. This approach can highlight the boundaries of space and identity that the nest embodies, positioning them as objects and as “experiential spaces” that invite reflection on both the tangible and the abstract. Light becomes a tool that shifts between the physical and metaphysical, revealing how something so solid can also be porous and evocative, much like the nests’ balance between security and vulnerability.

Viola’s work emphasizes that light can transform space and objects, making them both real and abstract. This technique encourages audiences to ponder what they see and what it represents on a deeper level. I feel that, in my work, embracing the concept that light can reveal “the soul” of a form while leaving parts hidden might bring additional depth to the themes of resilience, fragility, and coexistence.

I had to work within my budget constraints and make plans to use light to the best of my ability. A good plan was to borrow filters and use yellow-coloured cellophane paper to cover the lights, which were now already installed in the ceiling.

During this time a shift around materials and the space I worked with came

Wire, as a material, is laden with a practical and symbolic history. Its origins in industrial processes and its use in creating boundaries—fences, enclosures, and barriers—tie it to narratives of control, division, and exploitation. These associations reflect societal struggles such as displacement, systemic inequities, and colonial domination. Yet, in reclaiming wire as a medium for artistic expression, this history becomes a site of transformation. It shifts from a constraint tool to a conduit for connection and care.

In my practice, I repurpose industrial wire to create intricate, layered sculptures that resonate with themes of resilience and vulnerability. The barn, an icon of rural life and collective work, is a fitting counterpoint to this material. It evokes a history of shelter, sustenance, and shared labour—a space where narratives of survival and community have always unfolded. Together, the wire and the barn symbolise a tension between the imposed and the reclaimed, the industrial and the intimate.

This dialogue between material and space embodies the act of reclaiming narratives. By reworking wire into nests, I invite viewers to reconsider its historical associations. The delicate yet resilient nests represent the potential to weave new meanings into old materials. They are spaces of care and connection, countering the wire’s original purpose with a tender, human-centred approach.

Reclaiming narratives is not only about material transformation but also about reimagining histories. Once a functional space of labour, the barn becomes a gallery of reflection. The wire symbolises industrial might and becomes a medium of vulnerability and healing. Together, they challenge us to think about how objects and spaces carry stories—and how we might rewrite those stories to foster belonging and resilience.

This approach reflects a broader commitment in my work: to acknowledge the weight of history while also envisioning a future shaped by care, creativity, and connection. It is a practice of both remembrance and reimagination, a way of reclaiming the narratives that define us and finding new ways to hold them.

List of Illustrations

Bibliography

Considering the scientific background of my work, I think it essential to feel that I aim to create awareness on an aesthetic level.

The question arises of whether common goals and methods are sufficient requirements to recognize a person as a scientist, even if he/she is working in the arts field. Due to a systematical arrangement of knowledge and a correct rating of its validity, it is of great importance to keep strict limits between art and science. An artist cannot become a scientist just because he makes thorough observations, which he/she expresses in artistic verbal or non-verbal language. The fact that contemporary artists are used to working in labs together with scientists by doing experiments and producing innovative results (Wilson 2012) does not render them scientists: they are still artists and their work, independently from the fact that it is a result of experimental processes, is still an artistic one aiming both at aesthetic pleasure and at the renewal of the ways we subjectively perceive reality. Under this perspective, Franz Marc indeed paved the way for the forthcoming etiological theories. Still, he has always been a great artist, as he managed to influence, to a certain degree, the public’s mind.

11 Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, V8N3, 2016

Acknowleding Ruth Asawa – considering how to approach this part

Although Black Mountain College, the legendary postwar incubator for the avant-garde, launched the careers of many twentieth-century luminaries who would eventually enjoy international renown, the sculptor Ruth Asawa (1926-2013) never quite became a household name—instead, her oeuvre has so habitually been relegated to the household. When the artist debuted her wire sculptures in New York in the Fifties, critics dismissed them as decorative or housewifely. “These are ‘domestic’ sculptures in a feminine handiwork mode,” wrote one critic in a 1956 ARTNews review. Because Asawa worked with common materials, twisting copper and iron into undulating forms, her art is often scoffingly associated with that art-world anathema: “craft.” And so a three-room exhibition of Asawa’s works at David Zwirner cannot help but feel restorative, an opportunity to reassess both the expansiveness and consistency of her vision.

“What’s so interesting is that we’re at a period now when we’re constantly casting a backward revisionist glance to the art of the 50’s trying to find the artists who were overlooked because of sexism or racism… Ruth Asawa … she just jumps out as someone who is so deserving of being included in the art history canon, and I do think this show will absolutely elevate her reputation internationally.”— Deborah Solomon, art critic for WNYC

Listen to Review: Re-thinking American Post-War Art from WNYC >

From the 9/21/17 The New York Review of Books:

“When the artist debuted her wire sculptures in New York in the Fifties, critics dismissed them as decorative or housewifely. ‘These are ‘domestic’ sculptures in a feminine handiwork mode,’ wrote one critic in a 1956 ARTNews review. Because Asawa worked with common materials, twisting copper and iron into undulating forms, her art is often scoffingly associated with that art-world anathema: ‘craft.’ And so a three-room exhibition of Asawa’s works at David Zwirner cannot help but feel restorative, an opportunity to reassess both the expansiveness and consistency of her vision.” —Zack Hatfield, The New York Review of Books:

Her looped-wire sculptures explore the relationship of interior and exterior volumes, creating, as she put it, “a shape that was inside and outside at the same time.” They embody various material states: interior and exterior, line and